What is the problem?

The Ukrainian language has become a trend — one of the most popular language learning platforms, Duolingo, made such a conclusion in 2022. During the year of the Russian-Ukrainian war, more than 1.3 million people began learning Ukrainian. Interest in the Ukrainian language reached its peak at the beginning of the full-scale invasion by the Russian Federation, and has continued to this day. This fact is inspiring. However, no language applications can replace live communication with teachers.

What is the solution?

Rubryka already wrote about how Ukrainian was introduced as a class at Oxford in one of its materials. Now we have decided to collect three more stories of Ukrainian teachers who also help foreigners master the complexities of the Ukrainian language. Ukrainian teachers help not only with pronunciation, vocabulary, or grammar in their classes – they popularize Ukrainian culture and tell their students the truth about the war waged against Ukraine by the Russian aggressor.

Kateryna Tkachenko: "Ukrainian is a sign of elitism"

Kateryna Tkachenko, Ukrainian teacher at Anhui University (China).

Kateryna Tkachenko has been teaching Ukrainian to Chinese students for three years at the Anhui University of Finance and Economics. The professor received her philological education in Ukraine and went to China to get another degree in Economics. This became possible thanks to the Belt and Road Initiative, under which China cooperates with some countries in various business, trade, and cultural studies fields. Tkachenko studied Chinese for a year and then successfully defended her thesis.

After receiving a master's degree, Ukrainian was invited to stay at the university as a teacher of business disciplines. Tkachenko was a good match for the university because she knew Chinese and English. In addition, she was offered to teach her native language because in China, foreign teachers can officially work only on the principle of a native speaker. However, later it became clear that the university expected Tkachenko to teach Russian.

"When it became clear that I had to be employed as not a Ukrainian, but Russian teacher, the management's passion subsided," Tkachenko continued, "They told me: 'Who cares about Ukrainian, it's not even Russian.' Questions began, such as 'Are these different languages? Are there differences? And what's different?'"

Tkachenko then decided there were two ways: either she achieves her goal and popularizes Ukrainian in China, or she returns home: "I refused to teach Russian at another university where the provincial government allowed Ukrainians to do so. Stay in a foreign country for the sake of the Russian language? No, thank you. I have my own country, which is also full of prospects."

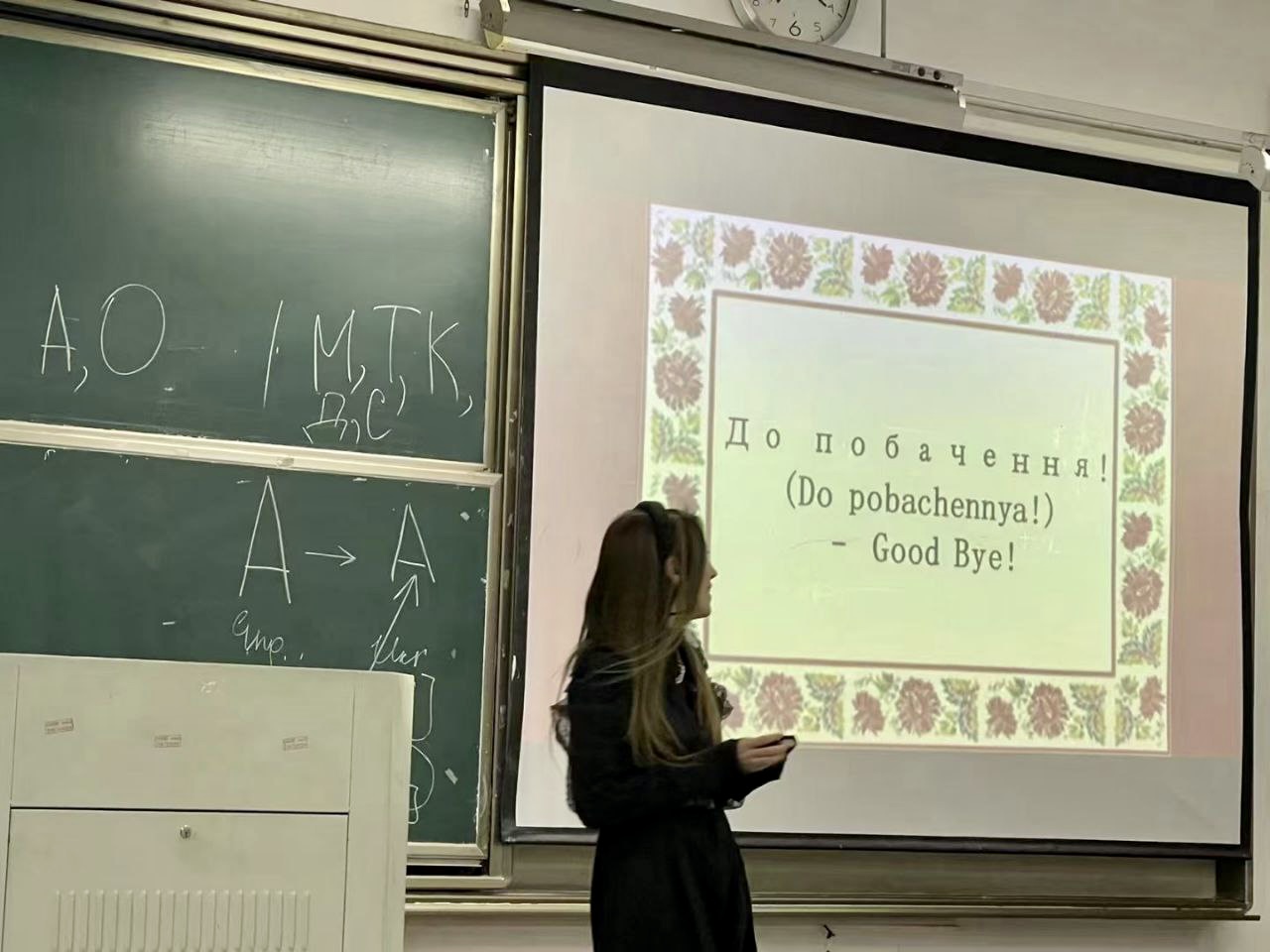

Tkachenko gives a lecture at Anhui University.

In the end, the university gave a probationary period of six months, warning that if it was not possible to recruit at least 20 students, the contract would be terminated.

Tkachenko began to act. It was a fundamental challenge for her. The Ukrainian convinced the university leadership through arguments about the countries' cooperation in the Belt and Road Initiative context. She spoke about the exchange of cultural experience, learning languages as a future perspective for building strong economic cooperation, and the possibility for the Chinese to obtain a Ph.D. in Ukraine. At the beginning of each lecture, she told the students about Ukraine and its cultural values. During the classes, she offered to subscribe to the Chinese YouTube channel about Ukraine and, in case of interest, to register for a Ukrainian language course. She also created a series of videos about the fact that learning Ukrainian will be much easier if you know even a little English. Everything worked out.

At the beginning of the launch of the Ukrainian language course at Anhui University, there were 100 students in the registration form. At the end of the first semester, there were already 254, and in the second semester — over 300, and as of today, Tkachenko's course already has more than 500 students.

"Honestly, at first, students registered because I am a beautiful foreign teacher because it is interesting and unusual," the teacher admits. "There were a lot of boys in the first semester. At first, I was sad, but later I realized that it doesn't matter what the motivation of a person who goes to learn a language is. Just imagine if Ukrainians switched to Ukrainian because other handsome Ukrainians communicate in Ukrainian! Ukrainization would happen much faster!"

Tkachenko says that, in general, the Chinese like to learn languages. In China, children start learning English from the age of two. There are many training centers, and nearly every kindergarten has a foreign teacher. That is why she made an original and effective marketing move: she offered to study Ukrainian phonetics in English. She created her own program that helps to pronounce Ukrainian sounds as clearly as possible.

"For half a year, we learn to read, learn simple sentences, questions, and only then I start teaching grammar," the teacher shares her know-how.

Tkachenko believes Ukraine should work on popularization of the Ukrainian language among foreigners.

"I use Ukrainian, English, and Chinese during classes. Students even joke about Teacher Kachu's — that's my Chinese name — trilingual system," Tkachenko shares. "The only problem is that this Ukrainian course is designed for only one year. Before Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, I discussed with the management the opening of the faculty of Ukrainian philology. It offered to open a faculty of languages of the Belt and Road Initiative with languages of the participating countries included. After the start of the war in February 2022, this idea was postponed for now. They have been waiting for our victory," Tkachenko told Rubryka.

The Ukrainian teacher notes that currently, Ukrainian is becoming a peculiar feature of the community of her students. For example, in their chats, they write various phrases in Ukrainian such as: "I love you," "goodbye," "How are you," "Good." That is, it is now a sign of progressiveness.

Tkachenko does not limit herself to teaching and educational work. She also participates in events. For example, recently, at a Chinese competition for foreigners, she performed the song "Ridna maty moya" in Ukrainian and Chinese, raised the issue of the war in her speech, and received a second-level award.

Generally speaking, according to Tkachenko, most Chinese know little about Ukraine and the differences between Ukrainians and Russians. Therefore, even the mere presence of a Ukrainian language teacher in China already prompts locals to seek answers to questions about what Ukraine is.

"We really need work on the popularization of the Ukrainian language among foreigners at the state level," the Ukrainian teacher believes.

Recently, Tkachenko created a YouTube channel to support Ukrainian-language YouTube and to tell Ukrainians about the language and experience gained in China.

In Tkachenko's opinion, opening a Ukrainian cultural center in China is necessary to strengthen the support and protection of Ukrainian communities and communities at the official level. This would give strength and confidence to many unofficial communities — kindergartens, schools, or centers of Ukrainian culture for children from Chinese-Ukrainian families — to be more active in China. It is worth strengthening media relations, introducing official communities of translators who could work on the distribution of Ukrainian content in Chinese, and strengthening the work of the Center for Ukrainian Studies in the People's Republic of China. All this will help to understand the identity of Ukrainian culture and customs.

"There are no people more interested in the spread of Ukrainian than ourselves. So, each of us should do everything in our power to introduce foreigners to our language and culture. Even simply speaking Ukrainian abroad is an invaluable contribution to the international community's perception of Ukrainians as a separate independent nation," says Tkachenko.

Victoria Ratushniak: "Seeing the pride in the eyes of foreigners when they speak Ukrainian is incredible!"

Victoria Ratushniak is a Ukrainian teacher at the online school Speak Well.

Victoria Ratushniak teaches Ukrainian online to foreigners at the Speak Well language school and also conducts private lessons for foreign acquaintances who want to learn Ukrainian.

Victoria is from Odesa but has been living in Kyiv for four years. After moving to Kyiv, her career as a teacher of Ukrainian to foreigners began.

"After moving, I, of course, looked for a job and received a call with an offer to teach Ukrainian to foreigners," Ratushniak recalls. "It was a complete surprise for me, and I was even a little confused because I am an English teacher by trade. However, I agreed and have never once regretted it."

She notes that after February 24, when Russia launched its full-scale aggression, the demand for learning the Ukrainian language increased wildly. For example, if two or three students registered for the course before the war, now it's five times more, with new applicants appearing daily. According to Ratushniak, this is inspiring because the majority came with a request to learn the Russian language before – but now, most foreigners do not want anything to do with the Russian language.

Ratushniak has students from Mexico, Germany, France, the Netherlands, Taiwan, Romania, and other countries. All of them are at different levels of language proficiency. Someone is just starting to learn it, and others already communicate freely on any topic. In general, but everyone has one thing in common — their work is related to Ukraine.

Yelmer is from the city of Groningen, the Netherlands. He is a volunteer and studies Ukrainian.

Yelmer is one of the teacher's students from the Netherlands. According to Ratushniak, Yelmer speaks Russian well, but he loves Ukraine, and works as a volunteer helping Ukrainian refugees, has many friends in Ukraine, and often visits. One day in class, he talked about his volunteer activities. He recalled a case when people spoke to him in Ukrainian, and he could only answer in Russian. Because of this, he was very embarrassed and ashamed. Since then, he began to study Ukrainian.

"I will say that the lessons are not only about cases and pronunciation. They are about life. We try to bring students to the minimum level of communication as soon as possible so that in a few weeks, they can communicate with Ukrainians," Ratushniak shares with Rubryka. "It's simple — to meet someone and tell them about yourself, order a coffee at a coffee shop, and talk to a taxi driver about the weather," says Ratushniak.

Unfortunately, according to the teacher, the material base for foreigners studying in Ukraine is quite small. "We have a textbook from the Ukrainian Catholic University, which we actively use, but about 50% of the educational material is our development: interactive tasks, search, and preparation of video and audio."

Ratushniak believes that the popularization of Ukrainian among foreigners is necessary, but she emphasizes that every Ukrainian should start this process themselves get to know their culture and history; and then, foreigners should follow the flow. They should be interested in the Ukrainian language, culture, and way of life not because they feel sorry for Ukrainians but because it is interesting. They will be interested in dressing up in embroidered clothes, listening to quality Ukrainian music, reading literature, and learning the language.

"I am inspired by transformation — external and internal. Finally, since the declaration of Ukraine's independence, we can now say loudly and proudly that we are from Ukraine — to see the pride in the eyes of foreigners when they speak to Ukrainians in Ukrainian and tell their friends and acquaintances about us. It's an incredible feeling to tell them about our culture and our history, our courage, and our freedom," says Ratushniak.

Anastasiia Borechko: "Language is also a weapon"

Anastasia Brechko, founder of the online school "nevgaMOVNO."

Anastasia Brechko is the founder of the online Ukrainian language school nevgaMOVNO, which teaches Ukrainian to children, adults, teams, and English-speakers all over the world.

Before founding her school, Brechko taught in public and private schools, created online courses, and later began teaching individually.

"People used to come to me with various requests regarding studying the Ukrainian language. Later, there were not enough spots, but I wanted to spread this love for the Ukrainian language. That's how the nevgaMOVNO school was born with a team that shares my values and our mission — to make people fall in love with the Ukrainian language and culture," says the teacher.

She started teaching Ukrainian to foreigners after the start of the full-scale invasion. Later, the school made a whole separate division for teaching foreigners because it required a different method and communication.

Often these are people connected with Ukraine. Among the adult students, some soldiers are fighting for the freedom of Ukraine. For them, learning Ukrainian is vitally important because their effectiveness and survival depend on communication on the battlefield.

"Another category of people are foreigners who study Ukrainian here to support Ukraine, to understand Ukrainian news and, in general, the context of the Russian-Ukrainian war. They feel that they want to help Ukraine. For us at nevgaMOVNO, it is important not just to learn words and grammar and read texts but also to delve into Ukrainian — we listen to songs, talk about the mindset and peculiarities of Ukrainians, and take virtual tours of Ukraine. We need to develop Ukrainianness!" emphasizes the school's founder.

Another highly motivated group of international students are children whose parents are Ukrainians abroad. Their children feel Ukrainian and do not want to lose this connection.

Philipp Tonev from the USA studies Ukrainian every day.

For example, one of the school's students, 10-year-old Philipp Tonev from the US, adores everything Ukrainian. Yellow and blue are his favorite colors — he even dyed his hair blue. During the school holidays, Tonev asked for Ukrainian lessons every day.

Rorik, the same age as Philip, is also from the US and has Ukrainian roots — his mother is Ukrainian, so he is interested in everything Ukrainian. He knows Ukrainian songs and memes, wears a T-shirt with the Ukrainian flag to class, and reads books about Ukraine's history.

Mark Dzyalak lives in Switzerland and collects money for the Armed Forces of Ukraine, and popularizes Ukrainian cuisine.

Another young pupil of nevgaMOVNO is 11-year-old Mark Dzyalak. He was born in Switzerland to a Ukrainian-Polish family. In life and at school, Dzyalak communicates mainly in German but runs a cooking channel and blog on Instagram in Ukrainian. Being only 11, he does culinary marathons, raises money for the Armed Forces, and spreads Ukrainian culture and cuisine abroad.

"We teach teams, children, and adults, to switch to the Ukrainian language and prepare for exams. In general, we just love the Ukrainian language and culture and want to share it," Brechko shares. "We need to show Ukrainian not as an office language but as modern and relevant, used in songs, films, books, podcasts, and memes. We strive to create a new image of the Ukrainian language and education in general."

The school also teaches foreigners who were so impressed by the Ukrainian country and the courage of Ukrainians that they decided to move to Ukraine, despite the war. According to Brechko, observing their euphoria and interest in everything around them is fascinating — it makes her love her country even more.

Brechko says that she sincerely admires people who decide to learn Ukrainian. It is definitely not easy, and the truly brave are capable of it.

"If the English language seems to have been created universal and unified — there are clear rules and a system, then the Ukrainian language was obviously created by very freedom-loving people," the teacher explains, "We have a lot of exceptions, synonyms, ambiguities. Ukrainian should be learned by delving into many contexts, but when you're already studying, it's as if you dive into a new world and start to see everything differently.

I would like Ukrainians abroad to spread the Ukrainian language and talk more about Ukraine and its traditions. Foreigners want this knowledge but sometimes don't know where to get it. Language is also a weapon, particularly in the fight against Russian propaganda, which penetrates into all world countries," Brechko is confident.

Even more useful solutions!

"Ukraine is the future of the civilized world"

Kateryna Tkachenko, dreamed of becoming an actress or announcer as a child. However, her mother suggested another direction and encouraged her to become a teacher of Ukrainian and English. She said the teacher would always have a grateful audience and go on stage daily. Tkachenko remembered her mother's words: "The Ukrainian language is the future of Ukraine. English is the future of the world."

"Now I would add: 'Ukraine is the future of the civilized world,'" says Tkachenko.

Thanks to the language, Tkachenko's childhood dreams did come true: she became a volunteer of the Yedyni team — a project on the transition to the Ukrainian language. There she realized herself as an announcer — Kateryna Tkachenko voices all audio versions of the Yedyni courses and as an actress — she also participated in making educational TikToks, engaged as a screenwriter, presenter of webinars, conversation clubs, and co-author of programs.

"The Ukrainian language made all my dreams come true and helped me become what I dreamed of since childhood. If you are reading this text but still do not speak Ukrainian, welcome to Edyni," Tkachenko says. "If you are a philologist by education, you can become part of the team and help people switch to Ukrainian! Maybe you will help make someone else's dream come true!"

Among the participants of the project are foreigners who study Ukrainian. For example, the German Stefan Far joined the project with a weak basic Russian language, and after a few months, he started writing poems in Ukrainian. Currently, Yedyni is preparing a collection of Far's poems for publication.

Both citizens of Ukraine and citizens of other states can become participants of the project, except for citizens of those states that voted against resolutions in support of Ukraine at the United Nations General Assembly – Russia, Belarus, North Korea, Eritrea, Mali, Nicaragua, Syria, Bolivia, Cuba, Zimbabwe, Sudan, Armenia, Venezuela.