The cult of math education in Ukraine and its victims

This column might initially make you feel disheartened about Ukraine's education, but by the end, it turns optimistic.

For weeks, social media in Ukraine has been buzzing with heated debates about whether math is needed for various fields and professions. The Ukrainian press has jumped on the hype, flooding us with discussions about the crisis and urging everyone to "invest in math education before it's too late."

I won't argue that things are bad, but the way people propose to fix this "bad" is nothing short of reckless educational populism — something that, instead of solving the problem, will only make it worse.

Imagine a wildfire raging through a mixed forest. Everything is burning, animals are dying, and the flames are devouring trees in their path. At this point, someone approaches the firefighters and says, "We need to save the maple trees." The firefighters, stunned, respond, "But there are other trees in the forest — oaks, birches. And what about the animals?" In return, they get a fiery speech about how wonderful maple trees are and how saving them is of the utmost importance.

Sounds absurd? Yet this is what it looks like when society becomes obsessed with fixing math education in schools, particularly in high school.

42% of Ukrainian students failed to reach the basic level of the PISA math assessment. Alarming? Absolutely. The results in other subjects, however, are just as troubling:

- 41% of students lack basic reading literacy.

- 34% struggle with fundamental science concepts.

Overall, Ukrainian students perform worse in most subjects than their European peers. There were plenty of reasons for this, even before 2020 when the pandemic hit, and after 2020 — let alone 2022, when Russia unleashed its full-scale invasion of Ukraine. No one should be surprised anymore.

Yet, despite the overall decline of the school system, the Ukrainian Facebook crowd insists on focusing solely on math. Let's call this the "isolated approach" — the belief that prioritizing a single subject will somehow lead the country to success and prosperity.

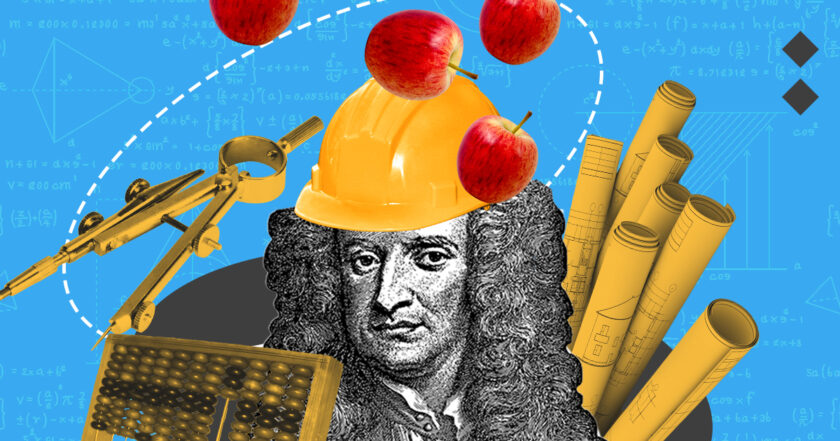

Math knowledge as a key to success

This is one of the arguments advocated by supporters of the isolated approach. It does have a scientific basis — studies show a correlation between good math grades in school and later success in life.

There's a significant limitation, though. As often happens with research interpretations, people confuse correlation with causation. These studies assess only math skills, but that's a somewhat disconnected way of looking at real life.

What does this mean?

Think back to your school days, or look at your child's class. Chances are, there's a group of so-called "straight-A students" or "high achievers" who consistently get good grades. And most likely, they're doing well across multiple subjects — not just math but also languages, arts, music, and more.

Many studies confirm a strong correlation between math and English grades, regardless of whether English is the student's native or foreign language.

Interestingly, one journalistic study compared students' math, English, and science grades. The results showed that the correlation between high English and science grades was more substantial than between science and math.

To put it simply — it's not just those who excel in math who tend to have better lives, but those who perform well in school overall.

An exclusive focus on math, at the expense of other subjects, can even backfire. Another study looked at adults skilled in math but unsuccessful in life. It found that they felt more frustrated and depressed than people with the same income level who lacked strong math skills.

At this point, you might be wondering — how is that possible? How can someone be good at math but still not succeed?

The reason is that the job market values two extra factors beyond subject knowledge: economic literacy (the ability to create and sell goods or services) and soft skills (the ability to work in a team and interact effectively with others).

In other words, math knowledge alone doesn't guarantee success. A person needs a broader set of skills across multiple disciplines to thrive.

"Okay, let's start with math — everything else will catch up"

The common idea here is that while math alone might not guarantee a child's success, there's no harm in prioritizing it. After all, why not make it the primary focus?

To see why this thinking is flawed, imagine a system of levers. When you pull one lever up, the others automatically go down. That's how decision-making works — when you prioritize one thing, you inevitably lose something in other areas.

Making math the number one priority means allocating more time or investing more money. And that money has to come from somewhere — specifically, other subjects.

Imagine we take a radical step: raising math teachers' salaries to $2,000 a month. They're thrilled! This motivates talented young professionals to go into teaching and work in schools. Meanwhile, wages for all other teachers remain below $500. How do they feel about this?

Teachers across the board are already struggling with difficult working conditions and low wages. Now, we add a stressor by singling out one group for special treatment. The result? Teachers from other fields start quitting.

Take biology teachers, for example — the ones training future doctors and agricultural specialists (agriculture, by the way, is one of Ukraine's key export industries). You could be a math genius, but that won't help you master human anatomy or botany at a professional level if no biology teachers are left to teach it.

"But we need engineers…"

Of course, Ukraine needs them, but even if we decide to sacrifice biology and focus entirely on math, it won't deliver the expected results.

Yes, we need a lot of engineers in absolute numbers, but as a percentage of the total workforce, they still make up only about 5–7%, even in the most advanced economies. In the US, for example, engineers account for just over 3% of the workforce despite the country being home to the world's largest engineering firms.

The problem is that between sitting at a school desk and working on assembling cruise missiles or even just drones, there are two more crucial steps: university and employment.

Now, imagine our highly paid math teacher successfully educates 20 students who all have the potential to become engineers. How many of them will actually enroll in Ukrainian universities?

Every year, thousands of Ukrainian graduates go abroad for higher education. And at the top of their list? Technical majors. One reason is that foreign universities have significantly better technological resources.

But there's an even bigger issue.

Even if, by some miracle, we manage to convince all 20 students to study engineering in Ukraine and they successfully graduate, what salaries will they be offered afterward? $2,000 a month? That might sound decent for Ukraine, but entry-level engineers can earn $5,000, $7,000, or even $10,000 a month in major companies in Europe or the US.

Year after year, we train talented engineers in our schools and universities and then send them to American and European firms, acting as a workforce donor for developed countries.

We don't lack engineers because our students are bad at math. We lack engineers because our economy isn't strong enough to keep our best math students in the country.

"So what should we do?"

First and foremost, Ukraine needs to avoid rushed decisions and stop searching for a magic wand that will instantly fix decades of accumulated problems in the education system.

Second, we need a comprehensive approach, not a narrow one. That means raising the baseline level of knowledge across all core subjects — not just math, but math included. The good news is that this is the direction of Ukraine's current education reform strategy.

Third, we have to accept an uncomfortable truth: for the next decade, the responsibility for training future engineers will partially fall on the companies that need them. These companies should already be stepping into schools, discovering talented students, and investing in them with an eye on future employment. Small but consistent investments in these students could compensate for the fact that Ukrainian firms can't yet compete with international companies on salaries for fully trained professionals.

And finally, we need large-scale retraining programs.

No matter how much we focus on long-term strategies, we don't need engineers ten years from now — we need them today. The solution? Career transition programs.

The greatest potential lies with former soldiers returning to civilian life. Many already have hands-on experience working with technology, the very field where Ukraine has the most pressing need for skilled professionals.