Valeria Kolodezhna is a geographer by trade and a researcher by calling. Before the start of Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, she worked as a school teacher and, at the same time, joined the work of the Ukrainian Nature Conservation Group (UNCG), a public association of scientists engaged in the protection of wildlife, and after the start of a full-scale war, in helping the nature reserve fund institutions in the occupied and de-occupied territories and recording the impact of the war on the environment.

In late spring and early summer, Kolodezhna toured the marshes of Polissia in Ukraine's north to film, preserve and pass on the beauty and value of Ukrainian wetlands to future generations.

Researcher Valeria Kolodezhna. Photo: Andriy Sahaydak

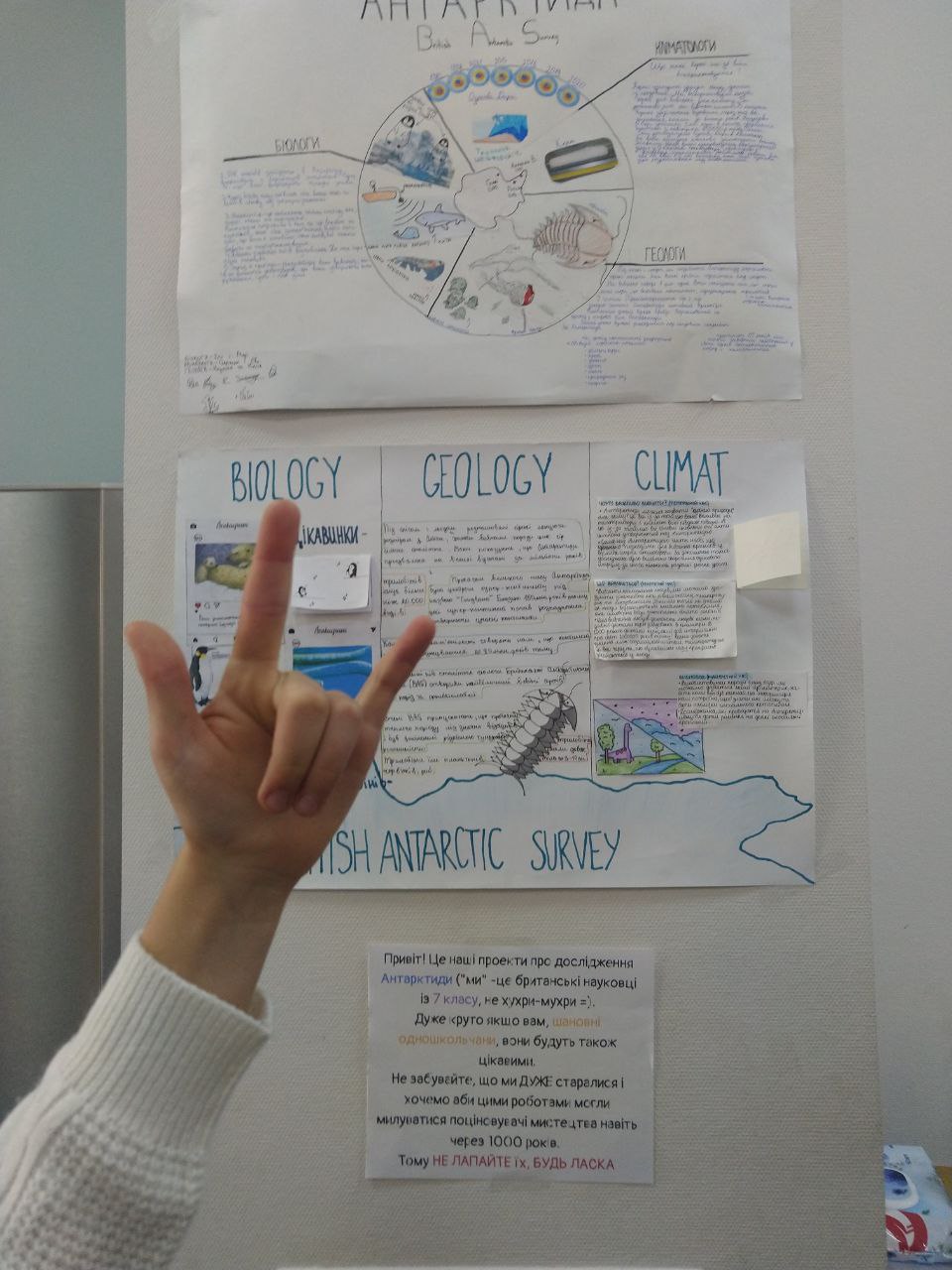

Now she and the team create interactive educational materials in the story map format within the National Geographic grant project framework. These materials will be useful to teachers and students but may be of interest to others. Interactive classes, research and experiments, explanatory videos, and maps — this is what the result of researchers should be.

What is the problem?

The school curriculum in Ukraine does not tell anything about swamps

Before the war, Kolodezhna worked as a teacher at a private school in Kyiv. It was a bilingual school with a double certification in America and Ukraine. "Our teachers had a lot of freedom. You could do whatever you wanted, even reinvent the curriculum, and I took advantage of these opportunities. It seemed that the existing curriculum was far from ideal, and I had a vision of improving it," she says.

According to Kolodezhna, school textbooks correspond to the ideas of the 80s — precisely the principles on which science and environmental protection were based when swamps were drained. The concept of climate is hardly mentioned in the curriculum, and the topic of swamps was a personal pain for Kolodezhna, an expert on wetlands.

"I had inspiration, looked for materials, rummaged through various American educational materials, and often used educational tools from National Geographic in my classes," Kolodezhna shares her journey with Rubryka. "These were various interactive classes and experiments. In the lessons, we often raised environmental topics, thought about why corals are fading and created plays with cartoon characters."

When Kolodezhna worked as a teacher, she made some additional materials gradually because she wanted more. She got to the point that when she returned to the Ukrainian program, she wondered why everything was so difficult in it.

Kolodezhna collected a whole database of educational materials. Photo: Valeria Kolodezhna

Kolodezhna's teaching practice ended on the first day of the war, on February 24. Many students are now studying abroad. All the developed materials, programs, and knowledge could no longer be applied in practice.

What is the solution?

Become a National Geographic Explorer and create online maps for learning

Left without a job, Valeria did not despair:

"A very active brainstorming process has begun. What to do next? I immediately understood that if I did not work with children, I would work with materials that could help children and teachers in super difficult conditions, not just online, but in conditions online and in bomb shelters," Kolodezhna says.

She started studying online courses and, at the same time, worked in the Ukrainian Nature Conservation Group. One day the explorer learned that there was an opportunity to apply for a National Geographic grant. The scientist immediately had an idea: to create methodological materials for school teachers that would tell schoolchildren about the value and beauty of Ukrainian swamps interestingly and interactively.

Kolodezhna explored Ukraine's nature during the expedition. Photo: Kateryna Harbarchuk

"They answered me on the last day of selection, late in the evening. I was very happy. On the one hand, tens of thousands of applicants applied for the project, and on the other hand, I had some inner confidence that I would pass. The application had questions that revealed the applicant's personality and plans for the future," Kolodezhna recalls. "You know, I sat with my diary and thought about this motivational side for myself, and even then, I understood and believed that everything was real, so I was very motivated."

With a positive answer, Kolodezhna received a special status: a National Geographic researcher. Next came the most interesting and inspiring part of the process — traveling and filming Ukrainian swamps.

"The swamps hardened me": fell into a swamp and was in the Chornobyl exclusion zone

Kolosezhna shares that during the two-week tour, she had to visit different places, with varying degrees of bans on visiting due to the status of the territories, the proximity of the troops, and potential landmines. At the same time, she realized an important thing.

"It is quite possible that during the next tens of years, the marshes will be inaccessible to visitors. Their demining of swamps is not a priority for the State Emergency Service, which is quite understandable. Therefore, the opportunity to film all this is an opportunity to prevent swamps from turning into blind spots on the map," she says.

Kolodezhna exploring one of the Polissia swamps. Photo: Andriy Sahaydak

In two weeks, Kolodezhna managed to travel through several regions — she visited Mizhrichynskyi Regional Landscape Park in the Chernihiv region. In Zhytomyr, there is the Drevlians Nature Reserve, closed even to tourists, located in the Chornobyl zone.

"We went to the territory forbidden to visit, the second level of radiation danger, also mined — the Kadyriv troops were stationed there. We walked along demined paths and launched a drone with the reserve's employees," Kolodezhna told Rubryka.

The explorer was also in the swamp, which is a buffer zone between two artillery ranges: "They shoot each other, and what falls — falls into the swamp. It was not scary because employees of nature reserve fund facilities and state security always accompanied us."

After that, she visited a nature reserve in the Rivne region, and according to Kolodezhna, it was one of the most fulfilling trips:

"There are unique massifs of upland swamps of Ukraine, located on its border with Belarus. The territory there is partly mined, there are many checkpoints and many prohibitions", but the obstacles were created not only by prohibitions due to wartime.

Once, the explorer fell into the swamp, but in time managed to grab a tree trunk, which saved her:

"All this (the project itself, — ed.) would have been difficult to do if I hadn't stood on that sphagnum (one of the moss types, — ed.), caught my balance, hadn't fallen into the swamp… I thought I went there to shoot, take pictures, and add videos to the background of the Storymap," Kolodezhna explains. "In fact, it is, but after the tour, I understood more deeply what a swamp is. I fell into a swamp, got bitten by midges, and had an allergic reaction lasting three weeks. It all helped a lot! I would even say that the swamps hardened me, and for that, I went. I would go again!" Kolodezhna says inspiredly.

Valeria is taking pictures of the area. Photo: Andriy Sahaydak

What will come out of it?

In Kolodezhna's team, all roles are divided: there is a cartographer who specially creates maps for the material, a motion designer, a communicator who will help with the distribution of the finished materials and several volunteers. Kolodezhna herself is responsible for the contextual content.

The result of the work should be three manuals in the form of an Internet page. All this is called a storymap or an interactive web page. In essence, this is a teacher's guide for three different subjects: biology in the 6th grade, geography of Ukraine in the 8th grade, and ecology in the 11th grade.

Photo: Kateryna Harbarchuk

All three textbooks will prepare students to answer the questions "What is a swamp?", "Why is it not scary but important?" and, of course, it will make students fall in love with these valuable elements of ecosystems. Anyone can use the materials free of charge and for an unlimited time.

Some of the materials will be tied to the Polissia marshes, i.e., what does the marsh do in the ecosystem of this region:

"Our vision is not only to explain to children what a swamp is but also to show teachers what a story map is, that it is not as difficult to create as it seems. Such a new format can re-inspire teachers to prepare for classes better," Kolodezhna explains.

Storymaps for education is the first experience for Ukraine

Storymap is a web page with embedded interactives: photos, animated images, and videos located between the text and created to explain the topic. They are an integral part of the material and continue the theme rather than simply illustrating it. You can play with these materials — scroll, click, and sometimes move the image. All this was created to make information more accessible and interesting for perception.

In the storymap, chapters often do not follow one another but go in parallel — you can switch between them and study different aspects of the topic. For example, one chapter may contain scientific studies that support the thesis mentioned in the main part, and another may illustrate a specific process in more detail.

The Times or National Geographic often uses this concept of presenting material, but it is the first time in Ukraine that it is used to create full-fledged educational materials.

One of the swamps visited by Valeria and the team. Photo: Valeria Kolodezhna

How to use storymap in class?

In Kolodezhna's project, one story map is designed for one 45-minute lesson. The teacher can choose activity options since any proposed topic can be developed. It will be enough even for extracurricular time.

Here are some activities for children that teachers can use:

- Debate club on the topic 'Which is more important: bog or peat?' with prepared cards;

- Experiments with sphagnum moss that grows in swamps;

- Recipes on how to make cranberry juice (specifically, using this example, you can explain to children that cranberries grow only in untouched swamps, but not in drained swamps);

- Watching cartoons about the superpowers of plants that grow in swamps, the history of interaction between swamps and humans;

"Instead of redrawing the structure of moss or teaching how this moss reproduces, you can watch a cartoon. Although, of course, we will also add moss propagation to the program to satisfy the teachers," Kolodezhna laughs.

One story map is designed for one lesson but can be stretched to extracurricular activities. Kolodezhna says: "I understand how valuable time is for teachers, so even if they dedicate one lesson to the swamp, I will be very grateful to them."

Will it definitely work?

After completing the technical part of the project, brainstorming webinars will be held with teachers on how storymaps can be used in the classroom. Some of them, who have already learned about the project, are ready to join the use of storymaps:

"Teachers with whom I worked before are delighted with the proposed idea, maybe because they are my colleagues. I didn't research what kind of demand teachers have for such materials. For me, creating such story maps is a solution to my personal pain, and I believe that there will be people who have the same problem," Kolodezhna says.

How will storymaps help and why studying swamps is on time during the war?

"We will sincerely say that the active hostilities have returned a sense of justice to many processes, including environmental ones, in Ukraine. This is a better chance than ever for people to look at the environment in a new way," Kolodezhna begins to answer the question.

However, the value for the environment is still not a strong argument for many. Therefore, there is another essential aspect. Wetlands are a world-renowned recognized buffer to deter military invasion:

"The Soviet authorities, and the Poles before 1939, planned irrigation systems and considered how much water should be left in the swamps, from which side an attack is possible. These are mercantile interests, but if there is no idea of bogs as valuable ecosystems, this user function of bogs can also be an argument for their preservation," explains the researcher.

Although, to understand the importance of marshes in wartime, it is even necessary to turn to history — the wetland massif on the border with Belarus played a vital role at the beginning of a full-scale invasion. If not for the difficult conditions that the swamps create for the passage of heavy military equipment, perhaps the northern part of Ukraine could have suffered much greater consequences of the war.

One more aspect is very important to instill in the heads of the next generation. Now, according to the old habit, swamps are not seen as places of great concentration of fresh water, which is becoming less and less, but as places of peat, amber, or cranberry gathering.

For example, the problem of illegal amber mining in the Rivne region has already become known throughout the country. Meanwhile, one of the largest swamps of Polissia continues to be destroyed by residents, making a living by selling mined amber.

Society must gradually learn; this is the explorer's main tool to protect these beautiful, sometimes dangerous, but very valuable places for Ukraine.

*Opinions expressed are the personal opinion of Kolodezhna and do not reflect the position of National Geographic.