Tetiana Zhuk, a Skidnyi Variant journalist, was sheltered by the city in 2014 when she left occupied Donetsk. But the war reached Mariupol. The woman spent the first 40 days of the full-scale war there. Of them, 25 were in the basement, burning and hiding everything that hinted at her profession to avoid capture.

This article is her story. It will be final in the Faces of Ukraine's Defense cycle, which Rubryka began at the beginning of the escalation to show how Ukrainians stood up for the defense of the Motherland, each on their front.

"We've seen it all before"

February 22. Mariupol. The square in front of the drama theater is crowded. Blue and yellow flags flutter in the middle of the crowd. People stand with placards, "Mariupol is Ukraine! Don't liberate us!"

Tania is among these people. With her red hair, she can't stay unnoticed. Tears come down the woman's cheeks. Acquaintances take turns asking why she is crying, but it's difficult for her to explain. Inside, she feels a rumbling mixture of elation and uncertainty.

She understood that there would be a big war. But she didn't know that the same drama theater would be destroyed in less than a month, and the European countries would promise to restore it after the war. At the same time, the people of Mariupol were imprisoned in the basements of their houses.

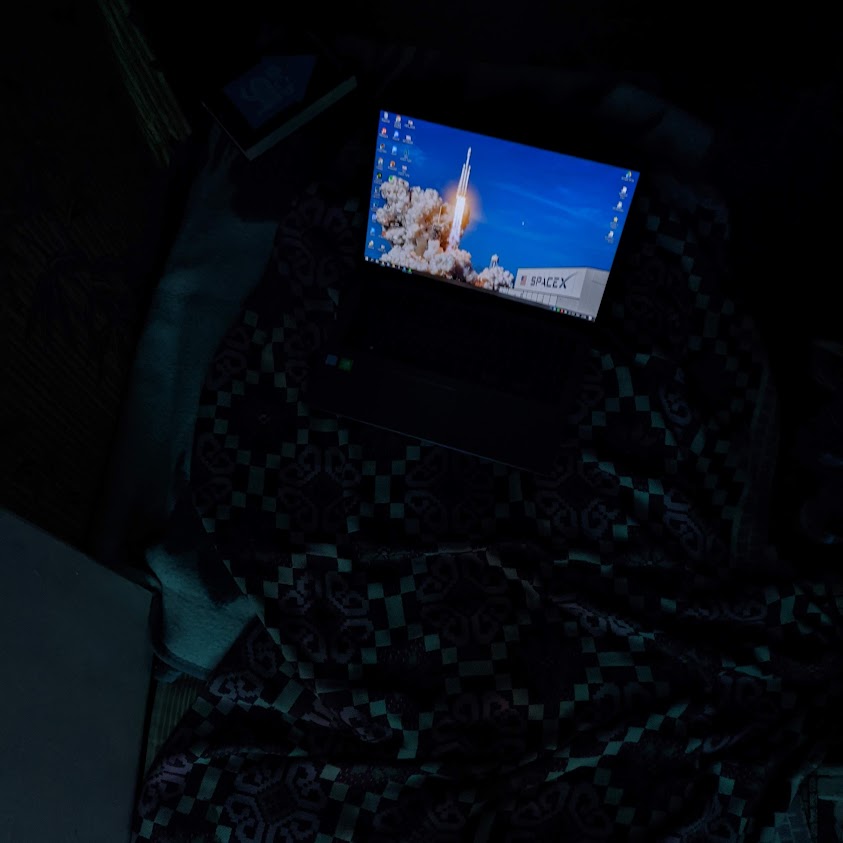

Tania and Danil during one of the air raids in Mariupol. The house still has electricity and all the utilities. "You can scroll through news and memes," the journalist jokes.

"On February 24, my boyfriend Danil woke me up. He just said: 'He attacked.' I immediately understood what was happening. But I thought there would be some kind of escalation in positions and provocation. I went to make coffee in the kitchen when I heard explosions. "Many residents of Mariupol, who lived on the city's eastern outskirts, have long been accustomed to distant explosions. I lived in the center, so I hardly heard such a thing. Then the windows shook a little. I was thrown into the cold but felt no panic," says Tania.

The woman emphasizes that she knew that if russia came somewhere, it would leave nothing behind, but she still decided not to leave the city.

Looking for a connection in Mariupol

"I'm a migrant from Donetsk. My boyfriend is a migrant from Donetsk. In general, there were a lot of migrants from there in Mariupol. We all had almost the same experience, but it played a bad joke with half, and the other half used it correctly.

Someone saw that the russians wouldn't stop, and they left urgently. Others, to whom I belong, thought: we have already seen all this. Nothing can be so terrible. We can stay."

"Much more likely to die than to survive"

When the hostilities in Mariupol became more intense, Tetiana's house was constantly shaking from the airstrikes. The blast wave blew away the windows, and the gas, electricity, hot water, and communication disappeared. The couple moved to the basement, where 23 other people lived in addition to them.

Photo from the basement. Children drew in the poor light of a flashlight or a candle,

"When we went down to the basement, of course, we didn't have the opportunity to take a shower or go to a toilet. And we were lucky because we could go up to our apartment and get some food there, and wash once every few days, at least somehow but forcing myself to climb up from the basement was the scariest part.

The building was constantly shaking. I needed to muster all the courage in a fist to make a march-throw up the stairs, quickly do everything, and return. We often talked in the basement about how stupid it would be to die while you stand naked in the shower," Tania shares.

She says that collective living in the basement erases personal boundaries. When you're around more than 20 people for a long time, you know about each other's skin, stomach, and nutritional issues. People tried their best to wash dishes, sweep and keep it as clean as possible, but it was still unsanitary. Like the people around her, the woman was afraid of diseases but was lucky. It was worse, Tania says, with thoughts of death.

"It always seemed to me that death was chasing us everywhere. We were more likely to die than to survive. If you don't worry about yourself, you worry about someone else. We have 25 people in the basement. You become close to these people and think: okay, these are 25 people. Fate and statistics cannot be so merciful that none of them die.

A crater from an aerial bomb in one of the yards near Tetiana's house

You prepare that something will happen to one of them, and you will have to think about where to bury the bodies. We all hoped for the best, but it was hard to imagine that it was possible to survive in a city where shells were constantly exploding. But we were fortunate."

"Destroying myself piece by piece"

As of the end of August, russians committed 435 crimes against journalists. Eight journalists were killed while performing editorial tasks, and nine were kidnapped. Fourteen were wounded. Fifteen have been considered missing, and sixty-five were threatened and harassed. And even these numbers are inaccurate until the Ukrainian side has access to the occupied cities.

Tania didn't need these statistics to understand that she was in danger. With her boyfriend, she invented the legend that she was a graphic designer. Then the couple began to hide the traces of Tania's real work. As a journalist, she wrote all these years about the war, torture, and abduction of people by the russians.

"I work with illustrations and graphic materials. I had a good legend. I left some of my most secure graphic works on my laptop, like happy new year postcards. I had to delete the stickers with quotes from Ukrainian poets from the East that I was working on because I understood that even they are dangerous.

There were people in our building who knew that I worked in journalism. One day, when we were already cooking on the fire in the street, I came to burn my business cards, different identification cards, and thank you notes. I scrunched it all tightly and threw it into the fire, and it did not catch fire. One of the neighbors came up and advised me to burn everything piece by piece so that it burned to the ground. He didn't ask anything else.

I burned everything. I also had some thank-you certificates, merch from the police, branded notebooks, and journalistic merch. All this had to be burned. Destroying myself piece by piece, as a friend of mine used to describe a similar experience. I constantly thought I was ready for any shelling, but not the occupation," says the journalist.

Ultimately, she hid who she was, even when the russian military came to their basement with inspections. As they said, they were looking for Azov soldiers.

One day, when we could hear automatic gunfire in the basement due to the street fighting, the language that the civilians heard outside changed to russian with a distinct russian accent. A little while later, there was a knock on the shelter door.

— Who?

— Open it. There will be an inspection!

The door opened. A man entered the basement, dimly lit by a single candle. It seemed to Tania that the bandage on his arm was yellow, the kind worn by Ukrainian defenders, but the girl couldn't see his uniform or chevrons because of the darkness. The military man declared that he was looking for Azov soldiers and was not interested in women and children. He walked through the basement, looking into the tired, dirty faces, but didn't ask for the documents.

When the man was already leaving, he was asked once again who he was.

— russian soldier.

That's how Tatiana realized she was still under occupation and shouldn't hope for a quick solution. She began to look for ways to get out of Mariupol.

"Yes, I've been writing all this time about how you torture people here"

"After that, we were forced to contact them [russians] often. When you leave the basement because you want to go to your apartment or the neighbor's, it is better to ask if you can go because you don't want to die from a bullet. They were, for some time, a source of information about ways of leaving the city. Of course, we understood that this information shouldn't always be believed because they lied to us that Kharkiv and Kyiv were already surrounded and ready to surrender. Dnipro and Zaporizhzhia are surrounded. That Kharkiv is a second Mariupol. I hate them for their lies, but I do not abandon the idea that they were also lied to by commanders to raise their morale.

Then rumors began to spread that there were departures from Donetsk. But I understood that they would check me there, and what would I tell them? Yes, I've been writing about how you torture people here all this time. And that's why this path was closed to us," the woman says.

Tania's workplace in the corridor in Mariupol when she was still staying in the apartment.

Later, she found out about the buses that could be used to leave. Tania and Danil agreed that they would be taken to the correct checkpoint. The driver didn't want to take money from the passengers, but they gave him 200 hryvnias. As Tania says, it was a ridiculous amount, especially in conditions where it was almost impossible to find gasoline.

"I remember the morning when we left. I constantly looked around the apartment. Everything became so freakish because once I looked at these things, I remembered how I bought them or how they were given to me, how much happiness they brought me, and now, how much pain is associated with them. The war just contorted everything.

I could barely pull myself together through tears, and we said goodbye to the entire basement. People cried or remained silent. It was tough to say goodbye," says Tania.

The bus used to take people away was painted with the letters Z. The journalist recalls that she was afraid to get on it because if the Ukrainian military saw a marked car, they wouldn't know whether there were civilians or military. The woman was constantly nauseous from the worries, but they reached the transshipment point in the end.

Tania and Danil left Mariupol but not the occupation. The photo was taken near Berdiansk. "I cried then because I understood that I would not see the sea for a long time," the journalist recalls.

From there, they came to the occupied Berdiansk, and only then, thanks to the efforts of Tetiana's editors, who found a driver and transport for her, the woman managed to leave for the territory controlled by Ukraine.

"I will never call these people again"

Tania is safe now. However, the experience responds and will remind of itself for a long time. She managed to get back to work relatively quickly. As before February 24, the woman writes about the war, the military, and people whose relatives have disappeared. She writes about children who were illegally taken to russia and about volunteers. And she writes about Mariupol, which has become home over the years of living there.

"I'm generally quite an emotional person. I cry a lot. It's my way of expressing my emotions. And when I left, there were moments when I saw the same tray that we had in Mariupol and thought: 'Well, we met.'

And once I interviewed in a cafe and saw a guy who looked like Sviatoslav "Kalina" Palamar, who was still in captivity then. I ran to the toilet and cried for about 5 minutes. I was just overwhelmed. And now I often see people who look like my acquaintances, which is very difficult.

And another important thing: since I worked in the city, I saw a lot of how Mariupol was being developed and how new places appeared. It is unfortunate to see how they are being destroyed. But it's even worse when you know many people through your profession and then discover they have died. I sometimes look at phone numbers and realize that I will never call these people or ask anything. It hurts," Tania shares.

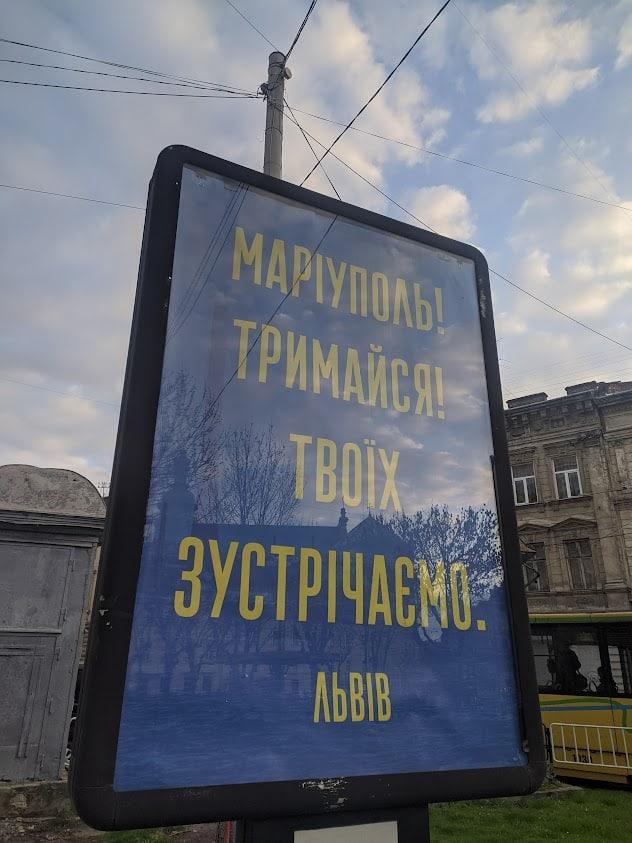

Citylight in Lviv, which touched Tania

The woman says that she tries to separate a part of her life from work, where she can joke, relax and find new strength. For example, on her Instagram, she posts memes, shares photos from vacations, and tries not to let much work there.

"I have Facebook for work, and Instagram is a personal space where I can post a meme. And sometimes people write, saying, how can you laugh, how is it possible? Do you know what happened there?

And I know. I write about it all the time. If I don't write about torture today, I write about death. And all this has a prolonged negative impact and affects me very strongly.

Many say that we journalists should be humane and adhere to standards. But it is also vital to remember we're now fighting an enemy that doesn't follow the rules and uses all the worst methods. It does not mean we should give up on everything, but there are times when the weapon must become more powerful to confront the enemy.

What is happening to the russian people now is the price for their impotence and their silent consent to what was happening. I think it's right when journalists talk about it honestly."

The article was prepared within the grant competition from the NGO Internews-Ukraine with the financial support of Sweden and Internews (Audience understanding and digital support project). The views expressed in this publication are solely those of the author.