Ukrainian Diaspora: 6 amazing facts about how identity was preserved away from home

A traveling suitcase, a rare poster of a famous French designer with a Ukrainian choreographer, and a choice between New York and Ilovaisk. Rubryka visited the Museum of the Ukrainian Diaspora in Kyiv. We report the most interesting facts

Back in 2010, there were approximately 10 million ethnic Ukrainians in the world forming a diaspora abroad. Now, eleven years later, this group has doubled; the times have changed, so have the countries of migration, the reasons, and businesses that Ukrainians do abroad. However, the only thing that hasn't changed is a living memory and a close connection with the homeland of Ukrainians around the world.

Rubryka visited the Museum of the Ukrainian Diaspora in Kyiv and learned the most interesting facts about Ukrainian diasporas who lived abroad, returned to Ukraine, or tried to help their homeland from afar.

The mystery of the poster and connection between the famous Ukrainian and Paul Colin

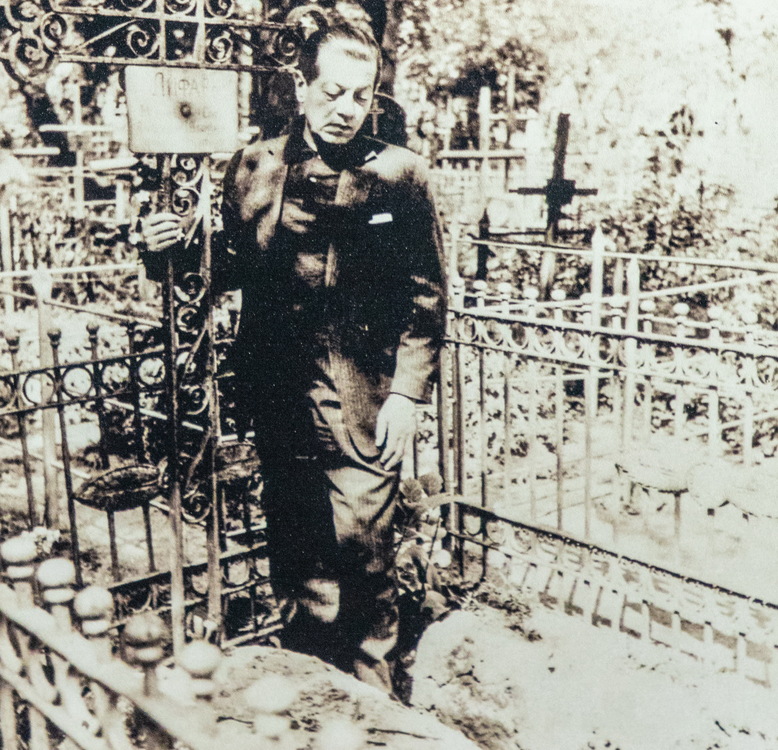

Ukrainians didn't forget their homeland. Serhii, or as he was called in France, Serge Lifar, a Ukrainian choreographer originally from Kyiv, who emigrated at 17, in 1923. He was not only a professional dancer but also a collector, bibliophile, and writer. After his death, he bequeathed all his archives to his hometown, but after his death, the transfer of archives has continued for 35 years. Some of them went to the Museum of the Ukrainian Diaspora:

"I often stop my gaze on the image of Lifar, created by the famous French designer, one of the most famous poster artists of his time, Paul Colin. This is a 1935 piece, a rare original exhibit," Oksana Pidsukha, the museum's director, explains.

Serge Lifar has achieved the highest recognition in Paris, and the confirmation is kept in the museum. These are two medals, one of which is a jubilee, issued to mark the 40th anniversary of Lifar's work at the Paris Opera in 1949 as an award given for his many years of service as a choreographer of the Paris Opera. There's also a 1956 commemorative medal to Serge Lifar from the Parisians, which was presented to him by the city hall.

The Ukrainian lump of soil emigrated abroad and returned 40 years later

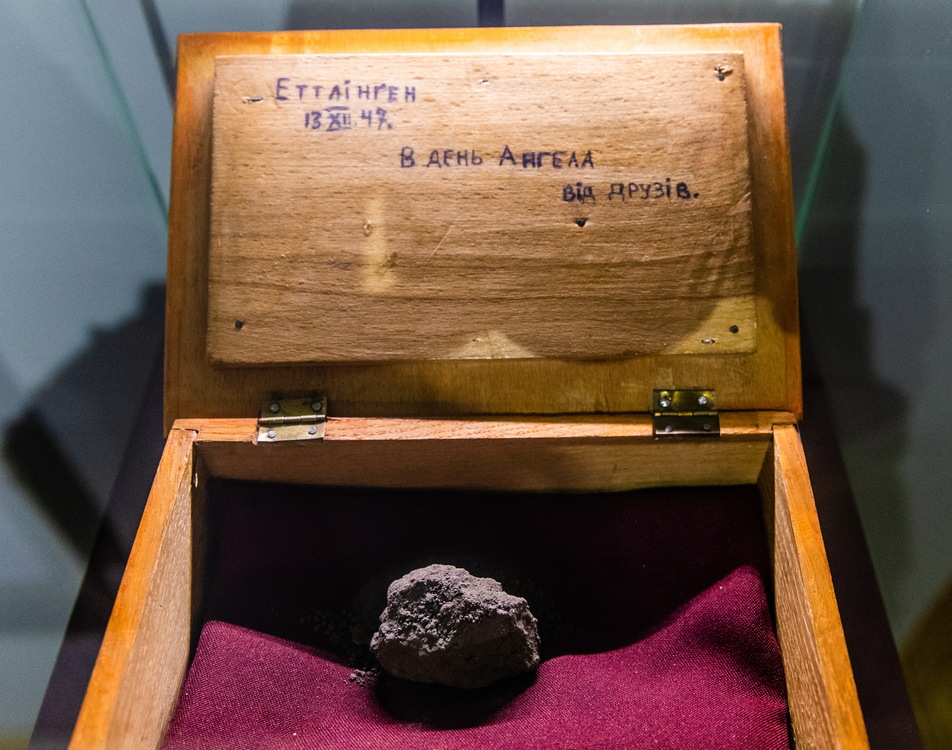

The same museum houses many exhibits that have long reminded Ukrainians abroad of their homeland. One of them is a seemingly ordinary lump of soil, which has a very unusual history.

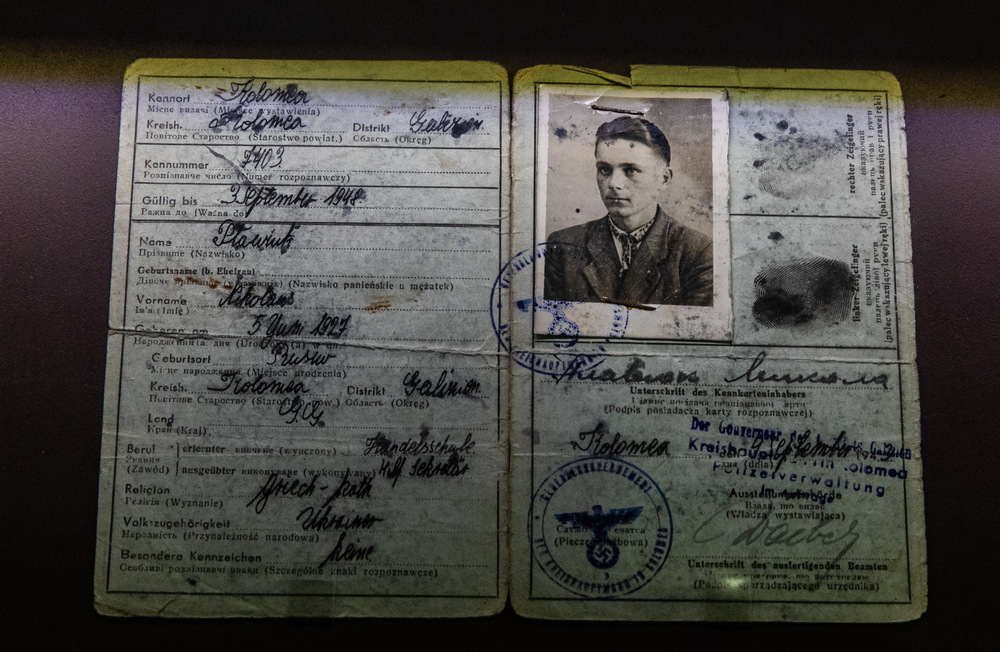

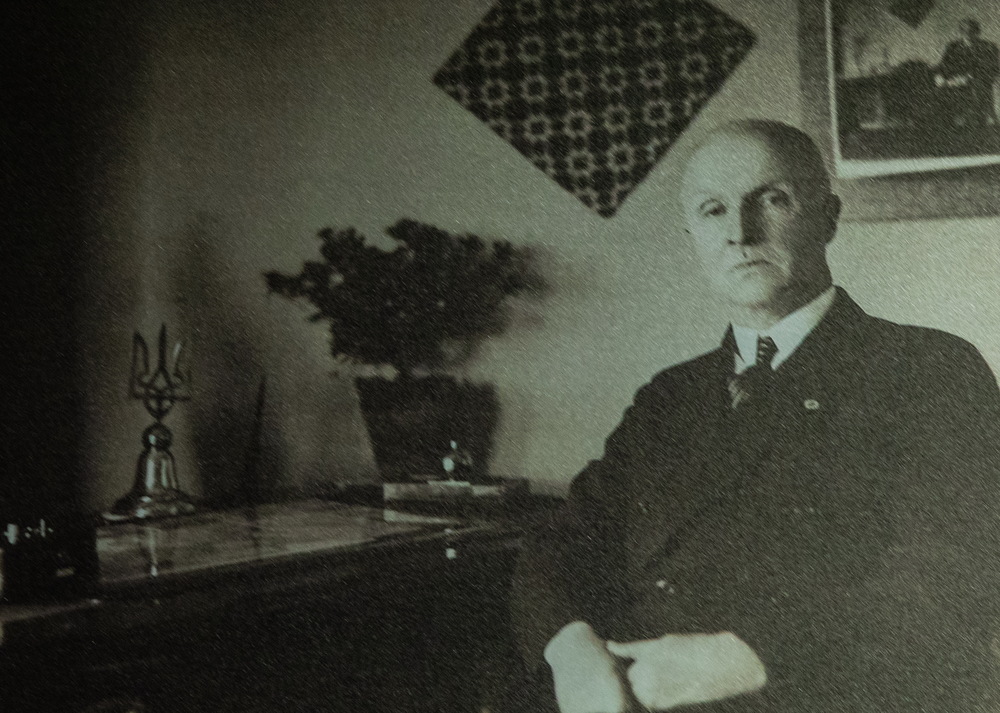

"This small lump of soil in a wooden box was given to the leader of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, Andrii Melnyk. There's an inscription on the box, dated 1947: 'On the name day from friends. Ettlingen.' We don't know for sure who took this symbolic gift from Ukraine to the German city, but we know Melnyk kept the precious memory of his native land until his death. Later, the box was inherited by the new leader of the OUN, Mykola Plaviuk, who brought it to Ukraine after independence," Oksana Pidsukha says.

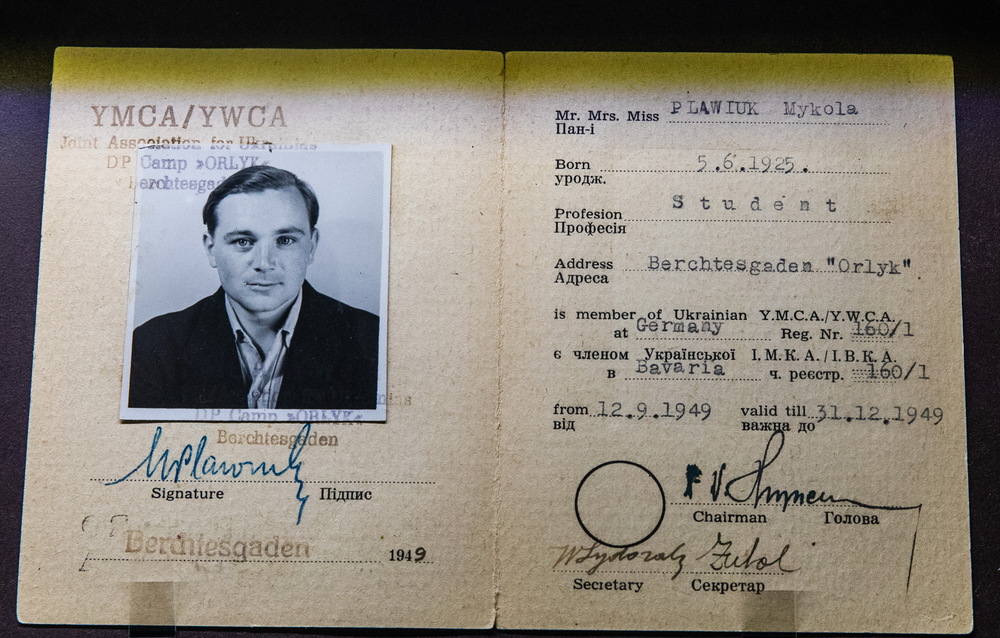

Mykola Plaviuk was a prominent figure in the Ukrainian diaspora, serving as President of the Ukrainian People's Republic in exile, an organization that maintained the longevity of the state tradition abroad after the defeat of the Ukrainian People's Republic. In 1991, when Ukraine gained independence, Plaviuk returned to Ukraine, handed over the presidential regalia to President Leonid Kravchuk, and received citizenship.

"The new exposition presents documents and personal belongings of the last President of the Ukrainian People's Republic in exile, which tell about his victorious struggle for Ukrainian statehood abroad. But the most touching exhibit is a lump of Ukrainian soil, which together with other exhibits was handed over to us by the director of the Oleh Olzhych Library, Oleksandr Kucheruk," Ms. Oksana comments.

Why did the artist's suitcase become an artifact?

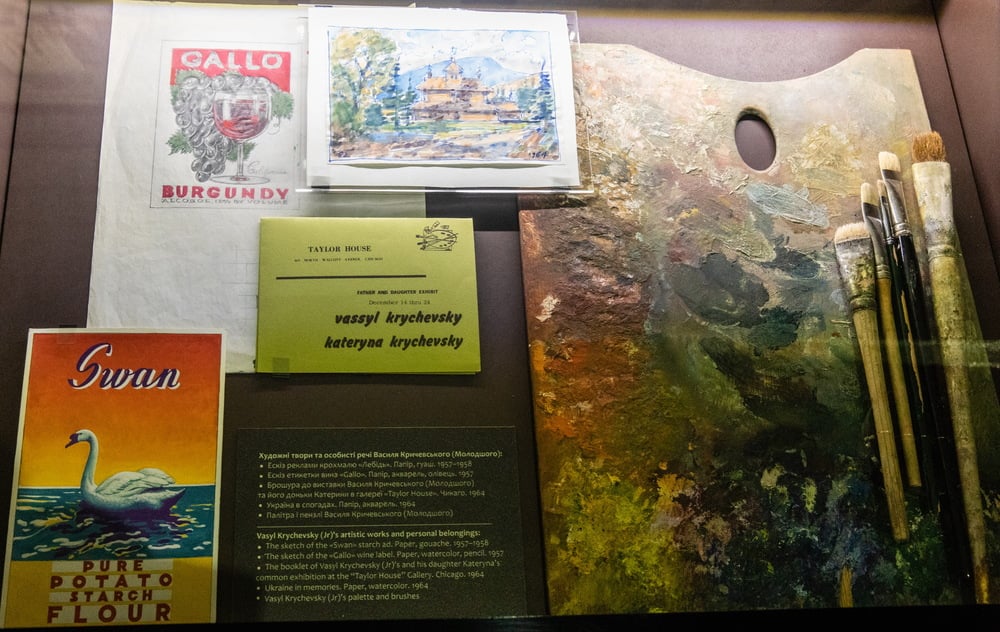

The red suitcase stored under the museum glass has an impressive history. It belonged to the outstanding artist Kateryna Krychevska-Rosandich, who turns 95 this year. She belongs to one of the most prominent Ukrainian artistic dynasties, left Ukraine at 17 in 1943 with her parents. After long travels in Europe, refugee camps, the family found itself in America in 1949 and found its second homeland and home there. But later the artist returned to Europe because she dreamed of learning the art from her uncle, the famous Ukrainian and French watercolorist Mykola Krychevskyi. With this suitcase in 1959, she was in Paris, Venice, and various cities in Germany. Stickers from different ports have been preserved on the suitcase, which one can use to follow the artist's path. It's just one of the many exhibits that Kateryna Krychevska-Rosandich donated to the museum. The exhibition presents numerous works of art and documents that acquaint visitors with the life and work of various members of the Krychevsky dynasty.

Diaspora made up where Taras Shevchenko and Abraham Lincoln met

Another feature of the Ukrainian people is strong empathy and readiness to always come to the aid of a loved one. Even thousands of kilometers from the native land, this characteristic doesn't disappear, but only intensifies, growing into great deeds. Proof of this is the securities of the first credit unions of Ukrainian diasporas, which are also now stored in the museum. How they got to the museum is a fascinating story:

"This story is connected with me," Oksana Pidsukha shares her memories. "In 2015, I went to America, presented a museum at the Shevchenko Scientific Society in New York. There I met with representatives of the Ukrainian diaspora and brought some archives home, which were donated to the museum. It was a roll of old papers that prompted us to research. In the course of scientific research, we discovered that there were rare historical artifacts among them.

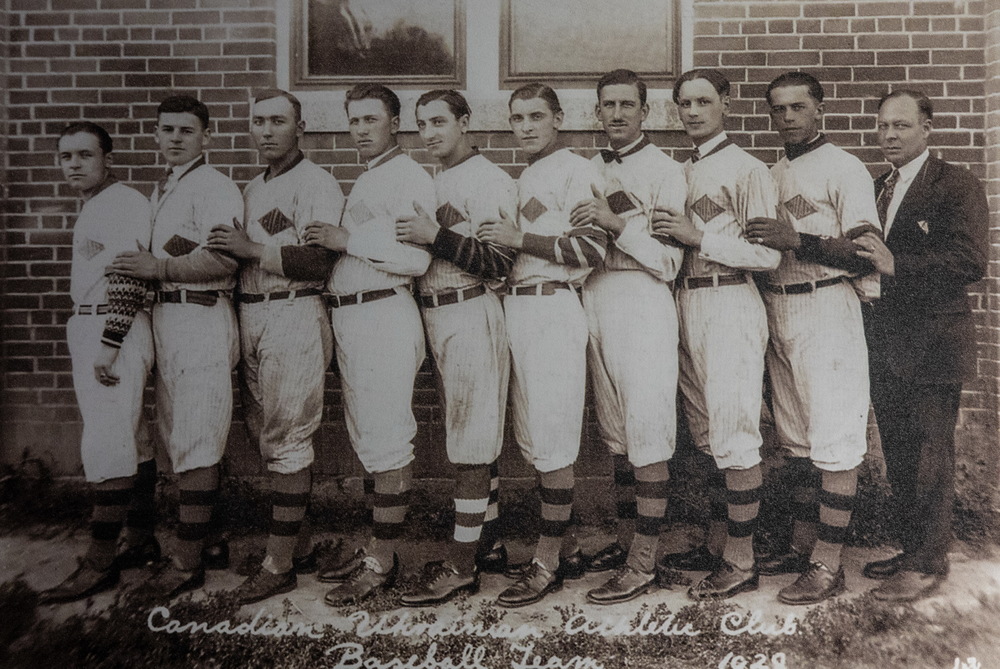

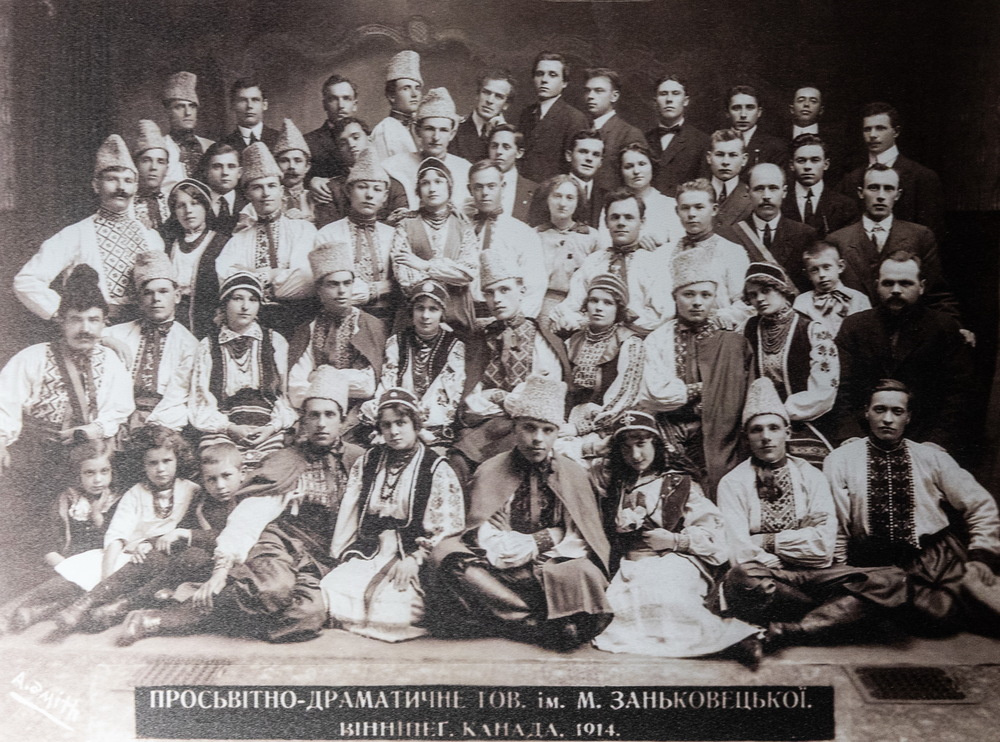

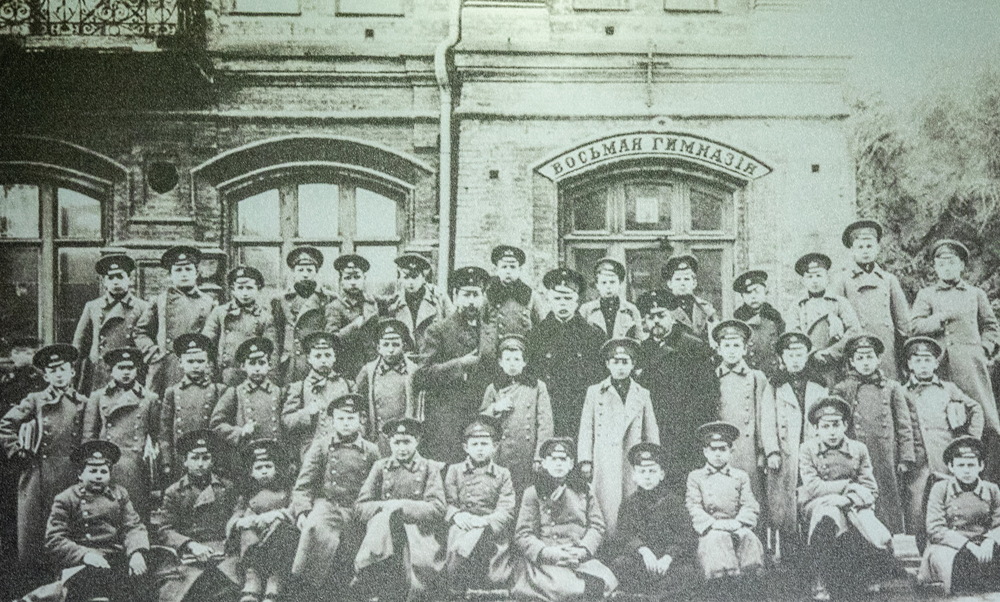

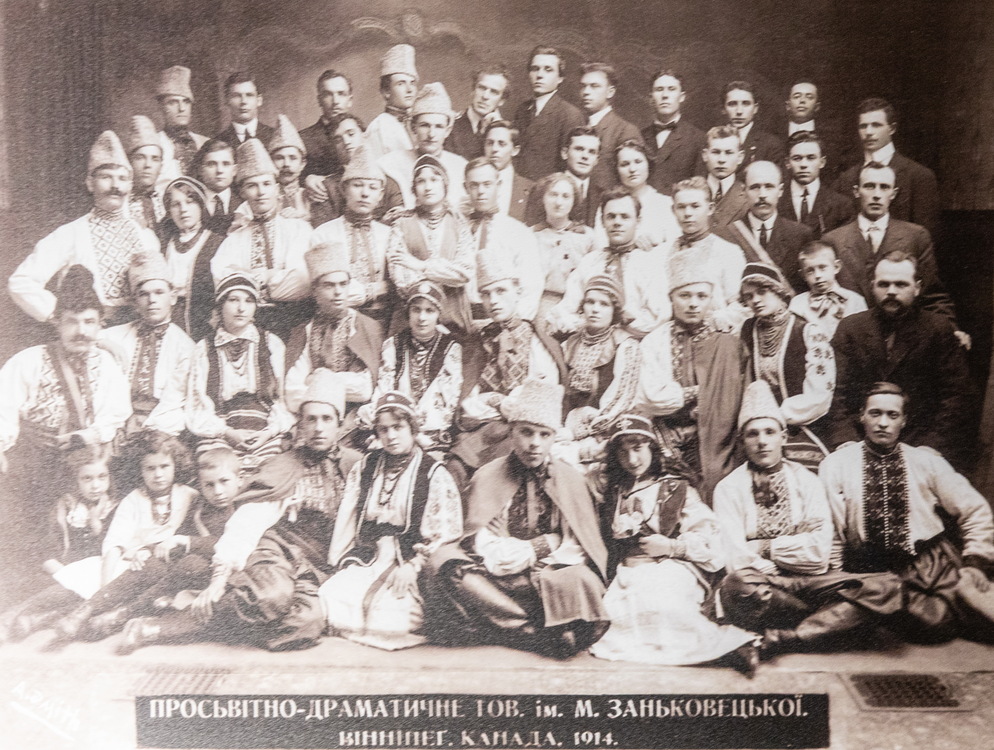

The presented documents deepen us into the history of the first Ukrainian immigrants who went to Canada and America in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Most of them were landless peasants from western Ukraine who couldn't earn a living in their homeland. But while most people went to Canada to explore "free lands," most people in America worked in mines or factories. Many Ukrainians, entire families, or even villages, went to industrial Pennsylvania, where they mined coal. Newly arrived migrants settled in compact groups or even founded their monoethnic towns. For example, Olivent in Pennsylvania was almost half inhabited by Ukrainians. It was there that the local mutual aid society "Consent of the Brotherhoods" was established, which, on the one hand, became the center of public and even political life of the city, and on the other hand, was aimed at helping the community. In modern terms, the "Consent of the Brotherhoods" played the role of a credit or insurance company.

Several documents of this society are displayed in the exposition. But the most striking is the 1917 membership letter, which depicts Taras Shevchenko, Bohdan Khmelnytskyi, George Washington, and Abraham Lincoln. The document has a refined design with Ukrainian ornaments and carries important meanings. The charter unites American presidents and prominent Ukrainians, shows respect for the new homeland and carries the memory of its history, emphasizes national identity," the museum's director explains.

Ethnic Ukrainians are returning home

Makian Paslavskyi is a Ukrainian born in New York to an immigrant family in 1950. He was brought up in a patriotic spirit, so in 1991, when Ukraine gained independence, he came to his parents' land and later moved to Ukraine altogether. He became a participant in both Maidans, and in 2014, he died in the undeclared Russian-Ukrainian war near Ilovaisk.

"For us, it's a very symbolic and important part of our museum collection and exposition, because we're talking about a Ukrainian hero who was an American by birth. Unlike us, Ukrainian citizens, he had no obligations to his historical homeland. But his love for Ukraine was instilled in his genes and brought up by his parents: Markian was educated in Plast, studied at a Ukrainian Sunday school, and read Ukrainian books. After Ukraine gained independence, a successful entrepreneur and US Army officer, Paslavskyi made his fateful choice by returning to his parents' land. Later he received Ukrainian citizenship and was one of the first to go to the front as a volunteer. His life ended near Ilovaisk in 2014. Paslavskyi didn't take care of himself, he chose the 'hottest' flashpoints," Oksana Pidsukha says.

"Initially, the idea of an exhibition in Paslavskyi's memory came about. We were lucky enough to find the hero's family in New York quite quickly. With their participation and the Maidan Museum in 2019 (on the 5th anniversary of the soldier's death), we opened the "New York-Ilovaisk: Choice" project. After the exhibition, the family donated Markian's memorial items to the museum for eternal storage. Some of them have been included in the permanent exhibition," Oksana says.

Some exhibits of the Museum of the Ukrainian Diaspora were found on eBay

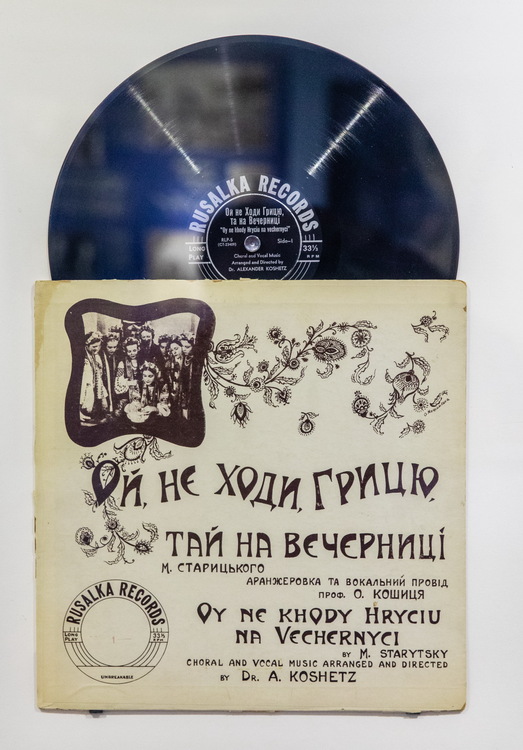

There the museum purchased a rare record with the recordings of Oleksandr Koshyts, an ambassador of Ukrainian culture who bought a choir in 1919 and went abroad to introduce it to independent Ukraine and its music: "He fulfilled his mission successfully, but couldn't return to Ukraine because of the defeat of the UPR," Oksana Pidsukha shares.

Oleksandr Koshyts was a choral conductor, composer, and teacher, whose fate threw him on the American continent. His legacy is also preserved in Canada. Finding and returning original artifacts related to the life and work of the genius Ukrainian musician to the homeland is not an easy but important task. Therefore, the museum made a lot of efforts to launch its collection in Košice. The original poster and one record were presented by the founder of the Museum-Archive of the Press in Ukraine Vakhtang Kipiani. Another one, or almost the first recording, made at the American studio Brunswick in 1922, was purchased on eBay by the American collector Eduard Khodorkovskyi and donated to the museum.

Photos Rubryka, from the archives of the Museum of Ukrainian Diaspora: