What's the problem?

Since Russia unleashed its full-scale war against Ukraine, Ukrainian libraries have written off 26,136,000 books. In 2022 and 2023, 66% of the scrapped books were in Russian due to Ukraine's decolonization law condemning and banning propaganda of Russian imperial policy. These Russian books were disposed of, but there was nothing to fill the empty shelves.

The issue of updating library collections was critical even before the Russian large-scale invasion. The onset of the war aggravated the situation, as library funding remained off the Ukrainian government's priority list. The availability of Ukrainian-language editions and books by contemporary Ukrainian writers in libraries is especially important for front-line and de-occupied regions, where libraries have become not just places to borrow books but also hubs for communication, leisure, and information exchange.

What's the solution?

Today, books are donated to Ukrainian libraries by charity foundations, benefactors, and volunteers. One of these activists is Oleksandr Sapronov, a teacher from the western city of Lviv. During the war, he helped libraries replenish their collections with modern books on his initiative.

How does it work?

For front-line libraries, hospitals, and military bases

Oleksandr Sapronov with books ready for shipping. Photo from Oleksandr's archive

Oleksandr Sapronov is a historian who spent most of his life in southeastern Ukraine. In 2019, he moved to Lviv, where he now teaches at a private school.

Oleksandr has been a book lover for as long as he can remember. Typically, he sells the books he has read through an online marketplace or book flea markets on social media. At one point, the activist had many books that "stalled" and didn't want to sell. Not wanting to give them away cheaply, Oleksandr posted in the Facebook group "Book Flea Market" that he was ready to donate two dozen books to a library in one of the front-line regions.

"About 40 libraries responded, and I felt a bit awkward that I could only help one," says the book activist. "So, I posted on my Facebook page that I had contacts from libraries and was ready to collect more books. At first, my most optimistic thought was to collect at least 50 books for two more libraries, but I exceeded my plan, and for almost a year and a half, I've been working in this direction."

Oleksandr and his wife, Anna, are the only members of the initiative's team. Sometimes, they get help, but usually, they collect and send books to libraries on their own.

Books come to the project in many ways—Lviv locals bring them personally; people from other cities send them by mail; authors, publishers, different public organizations, educational institutions, and diplomatic missions also contribute. Oleksandr collects all these books in one place and prepares packages based on the requests and types of libraries.

"There are different libraries—municipal, district, rural, school, children's libraries, libraries in hospitals, and military bases. Each has its specific needs, and I try to assemble packages that best suit the type of library and the region where they are located. For example, if there's some local history literature or a novel with a clear setting, I send it to the region the book is about," says Oleksandr Sapronov.

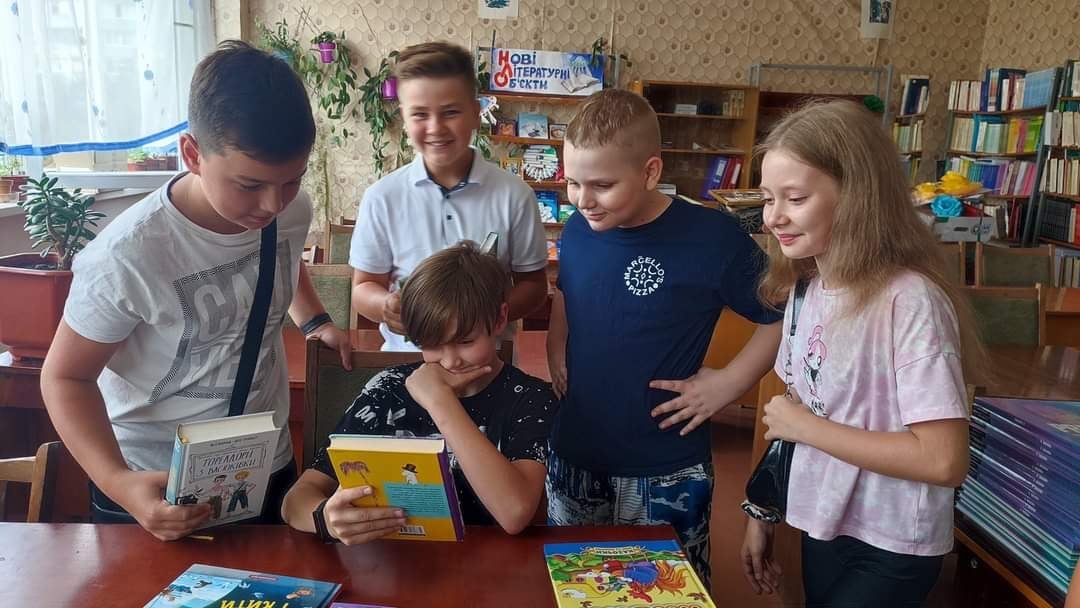

Students of School No. 4 in the northeastern town of Lozova, Kharkiv region, in the school library. Photo from the archive of Larysa Shterman

Oleksandr says libraries usually need children's literature the most because it is always in high demand. Next in line are fiction works by famous Ukrainian writers — Andrii Kokotiukha, Liuko Dashvar, Serhii Zhadan, Nina Fialko, Yurii Vynnychuk, and Maks Kidruk. They also request literature on Ukrainian history but more popular works rather than specific scientific monographs. The main topics are World War II, the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, Ukrainian dissidents prosecuted by the Soviet regime, the Revolution of Dignity, and the Anti-Terrorist Operation.

It's a different story with libraries at military bases and hospitals. Oleksandr Sapronov notices the demand for various kinds of literature, which he selects separately based on a request. Soldiers often ask for "men's" literature, but not about the war. They need detective stories, life novels, psychological and motivational books, fantasy, science fiction, and history—everything that helps soldiers relax and rehabilitate.

"They don't often request specific books because they are hungry for books, so they are happy with anything. We especially felt the demand after the centralized removal of Russian and Soviet collections from libraries. Filling the empty shelves is a pressing and painful issue," says Oleksandr Sapronov.

Does it really work?

"Library photo reports are the most favorite thing"

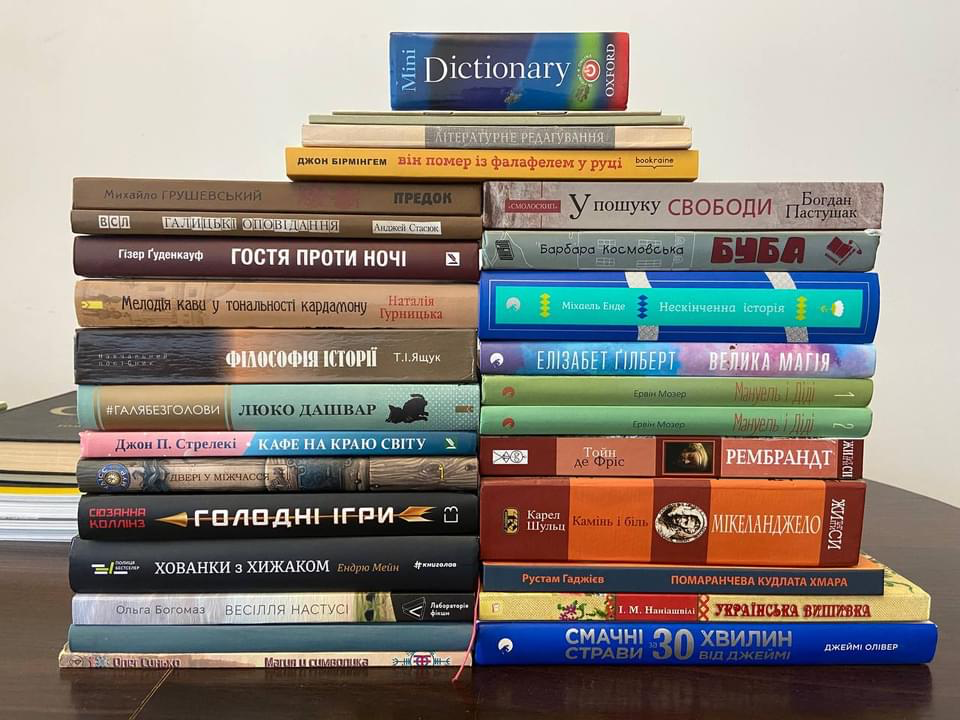

Package No. 218 to the library of the village of Naryzhzhia in Ukraine's central Poltava region. Photo from Oleksandr's archive

In a little over a year, Oleksandr Sapronov's initiative has collected about 7,000 books, replenishing the shelves of more than 200 libraries. Ninety percent of these libraries are in front-line and liberated regions, from northern Kyiv and Chernihiv to southern Mykolaiv and Odesa.

The project tries to respond quickly and efficiently to help libraries that suffered from Russian occupation, destruction from combat, or shelling. Requests from such libraries are processed out of turn. Some packages were delivered directly to front-line communities by car through charity organizations, as mail service doesn't operate there.

According to Oleksandr, every photo report from libraries is a special story where he feels his work has finally reached its endpoint.

School librarian Tetiana Liahusha presents books received from Oleksandr Sapronov. Photo from Tetiana Liahusha's archive

For example, the library of Bilozerka Secondary School No. 13 in the eastern Donetsk region has already received two packages with about 60 modern books from Oleksandr Sapronov. The librarian, Tetiana Liahusha, comments:

"I always get distraught when I can't satisfy the reading requests of our young bookworms, our grades 1-11 students. Our children are interested in reading and often visit the school library. But sometimes I can't offer them anything because they've read all the literature in their age category and area of interest."

Ms. Tetiana says that after the school library wrote off a lot of outdated Russian-language literature, they received only a few specialized subject manuals.

"I constantly faced the problem of replenishing the library's collection," Ms. Tetiana continues. "We often hold charity events with students and parents like 'Favorite Book as a Gift to the School Library,' collect and sell waste paper. With the money raised, I buy modern books based on readers' requests and the school curriculum. While searching for affordable books, I went deep into many online groups selling used books, like 'Book Flea Market,' 'Reading for Children,' and others, where I saw Oleksandr's offer to help libraries."

The Lviv teacher's initiative brought many diverse books to the Donetsk region: reference literature, books for younger and middle school students, and even some English books for toddlers.

Unfortunately, the library is now in a zone close to combat operations, and the school operates online. According to librarian Tetiana Liahusha, children still come to the school library to borrow books. The library also conducts online events to promote reading and hopes that the school library's collection will be successfully updated with modern Ukrainian and world literature.

Students of Lozova School examine books from Oleksandr Sapronov's initiative. Photo from Larysa Shterman's archive

For a year now, books from Oleksandr Sapronov have been in the library of School No. 4 in the northeastern town of Lozova, Kharkiv region. According to Larysa Shterman, the head librarian, the school library had not received new books since 2013 until it participated in Oleksandr's project. The problem with collections is acute, and everything depends solely on the librarian's initiative.

"Interest in reading has only increased during the war," says Larysa Shterman. "We have frequent power and internet outages because we live in the front-line zone. Education is only online. Parents of younger students, paying attention to their children's reading skills, enroll them in the library because books are expensive now, and not every family can afford them. The nearest bookstores are in [the regional center city of] Kharkiv, and online orders also come with shipping costs."

"Our school has 1,300 students — plenty of readers. Thanks to Mr. Oleksandr's initiative, we also have books to read," says Larysa Shterman.

Books received by the Public Library of Lozova City Council. Photo from Svitlana Vovk's archive

Svitlana Vovk is also from Lozova. She manages the Lozova City Council Public Library, which has 28 village library branches.

"With the start of the war, many readers developed a strong aversion to everything Russian, including books," says Svitlana Vovk, stressing the demand for books in the Ukrainian language. "The situation with Ukrainian books is challenging: the ones the library has been read almost to smithereens, and buying enough new ones to satisfy readers' demands is unrealistic. So, Oleksandr Sapronov's project was an incredible surprise for us.

Thirty, forty, fifty modern Ukrainian books for a village library is a real treasure."

The librarian, Svitlana Vovk, is delighted—now the halls of village libraries in the Kharkiv region are no longer empty but gradually filling with new literature and introducing readers to modern authors. The latest arrivals bring so much joy to children who choose only Ukrainian books.

Even more helpful solutions!

"Everything we do is for the long run"

Oleksandr Sapronov is packing books. Photo from Oleksandr's archive

Oleksandr regularly posts calls for book donations and updates on packages sent on his Facebook page.

Sometimes, people ask him why he collects books, spends time packing, and regularly hauls heavy boxes to the post office. A few times, people told him they had books to give away but doubted anyone would read them.

Oleksandr responds that some books may sit on a shelf somewhere, but, in other places, they might lead a child or an adult to quality Ukrainian literature or spark an interest in history even if they don't change someone's life. Moreover, libraries stay in contact with each other and exchange books, so if a book isn't needed in one library, it will find a reader in another.

People also ask why he sends English-language books to village libraries.

"Every village has English teachers and children learning English who want to study abroad. English books are scarce in Ukraine and expensive. So if a teacher and two kids in a village read an English novel by Dan Brown, then it was all worth it," says Oleksandr Sapronov.

The historian explains that what he and other book volunteers are doing now is a long-term effort. Bookshelves in libraries need to look solid. Over time, some books will be weeded out and optimized from quantity to quality, but that's only possible with the initial step of filling the book gap. According to him, Ukraine is still at this stage.

The Molfar Publishing House has donated an entire pallet of their comics to libraries. Photo from Oleksandr's archive

Some people believe libraries are outdated and no one goes there anymore. Oleksandr believes it all depends on what the library can offer its readers.

"This is partially true, but only partially because if there's no offering, there's no reason to go. I once stopped going to my village library because I read everything that interested me. I knew the placement of the books on the shelves by heart, and the only new arrivals were periodicals and some professional journals," says Oleksandr. "If a librarian has updates and suggestions, people will come. In a store, school, or church, someone will mention that the local library has a new book related to a popular TV series or by an author who is currently serving in the military, and people will definitely go to check it out."

The activist adds that village libraries are not relics of the past. Many times, librarians have told Oleksandr that people come to the library not only for books but also for communication and inspiration, as front-line communities have minimal public life right now. Clubs and cultural centers are not working and don't hold concerts, and schools are on distance learning. The library remains the only place for social interaction.

Books for the public library of Solonytsivka Village Council, Kharkiv region. Photo from Oleksandr's archive

Oleksandr Sapronov shares a personal revelation: the library world of Ukraine is alive and eager to develop. Libraries are not relics of the past; they are actively changing and becoming cultural centers of their communities. The main obstacle is the need for more funding. Often, school, village, and small-town libraries survive only on the enthusiasm of librarians and the help of volunteers and foundations.

"What does this work give me? I always wanted people to read more, and I wanted Ukrainian books to finally overcome the dominance of Russian ones in bookstores and libraries," says the volunteer. "This is my small contribution to making the public space more Ukrainian, especially in regions where the Ukrainian culture has always been in the minority, overwhelmed by Russian books, music, and cinema. I want to see Ukrainian authors and books on library shelves, not endless Lermontovs, Yesenins, and Kataevs."

How to help the project?

You can support Oleksandr Sapronov's volunteer initiative in many ways:

- DM him on Facebook and arrange a meeting to hand over books in Lviv or send books by mail.

- Donate to buy books for libraries. The project has accounts for fundraising and PayPal for international transfers. "I know how to find discounts and promo codes on publishers' websites, and I have dozens of sellers on the secondary market who will sell me a book for less than it costs in the store," says the project initiator.

- Often, books are donated by authors or publishers, so if you are one and also want to participate in a good initiative, join in.

- You can organize a book collection in your building or at work and send it to Oleksandr or receive library addresses to send packages independently.

- Participate in a charity book raffle, which Oleksandr Sapronov regularly organizes—the proceeds from the lottery help libraries in front-line and liberated areas.

How not to help? Do not send literature published during Soviet times. Oleksandr Sapronov always stresses that he does not accept Russian-language or Russian books.