The Sumy region suffers from russia's shelling every day. The Telegram channel of Dmytro Zhivytskyi, the head of the Sumy Regional Military Administration, resembles the State Emergency Service news feed.

"June 20. Today, around 6:30 am, the russians shelled the Seredyno-Budske community from their territory. Artillery fire, 30 hits. There are no casualties or damage."

"June 21. The night in the region passed relatively quietly; there was no shelling.

But yesterday evening, two employees were injured when a police car blew up on a mine while patrolling the Okhtyrka district.

A second explosion sounded when deminers and investigators were working at the scene. As a result, five more were injured.

One person died on the spot."

"June 21. The enemy continues to attack the Krasnopillia community.

This afternoon there were four shellings from mortars and other types of weapons.

We record a total of 42 hits on the territory of the community. The russians also attacked populated areas, damaging houses, farm buildings, a school, and a village council. Enemy shells destroyed a cozy park in one of the settlements of the community. Fortunately and surprisingly, none of the people were injured during the shelling. But today, there was an attack by kamikaze drones on the community's territory. Four people were wounded, and two were in serious condition in the hospital. The car was also damaged."

It is every day. That has been the typical life of the Sumy region, which isn't lucky to border the aggressor country.

We drive past destroyed villages. Outside the window, we see a contrast we can't get used to: the destruction inflicted on the region by the russians and the vitality of Ukrainian nature.

Boromlia Village

Strawberries and removing rubble

The village was occupied for almost a month. We stop in the center, where they have a small bazaar, and locals, mostly older women, sell strawberries, eggs, and honey.

Gesticulating, the Icelandic photographer Oskar communicates with the older women, Nina and Ira.

It's difficult for them to understand each other, although he has been living in Ukraine for several months, married to a girl from Odesa, whose grandmother he calls "granny." He says that the Ukrainian language is warmer than russian. Women complain people buy little from them. Fortunately, their houses are almost intact with broken windows only.

Almost all the houses around are destroyed. Cafes and shops are damaged and not working.

The center of the village has several fenced-off craters from air bomb explosions.

Another bomb was dropped by a jet at a kindergarten at 6 am. Near one of the destroyed buildings, the gas company premises, we see many people taking the rubble apart, carefully stacking the surviving bricks, and looking for what can still be used for construction.

Volunteers from Sumy and the entire region are working here. Oleh Strelka, a spokesperson for the State Emergency Service's central administration in the Sumy region, says it is the eleventh trip to the area from the city of Sumy. Trostianets, Lebedyn, Okhtyrka, Boromlia—when these towns are shelled, and as soon as a post about needing help appears on the Dobrobatsumy Telegram channel, a massive line of people willing to help immediately emerges. Because of difficulties with fuel, it is challenging to transport all those willing to help; there are much more issues than opportunities to involve people in the cause. All volunteers are instructed because you can sometimes find a shell or grenade even in places checked by sappers. Rescuers supervise them. When volunteers find an explosive object, they must immediately raise their hand; then, sapper service employees remove the items. But only employees of the State Emergency Service work at the most complex and dangerous facilities.

Stanove Village

Fishing and shells

People found a russian tank in a local lake; the Ukrainian troops shot it during the retreat of the russians. The Ukrainian Armed Forces pulled out and took away the tank, but the part of the ammunition that didn't explode was scattered all over the water area of the lake. So now here, diver sappers are searching for munitions on the bottom. Working conditions are complex; the water is very murky, and the bottom is muddy. They need to carefully examine the bottom with the help of metal detectors very slowly, almost to the touch. We see how four tank shells are pulled out of the water.

Nearby, children pass by us returning from fishing.

They say they like fishing and are not afraid of shells. Sappers say any ammunition can pose a danger to anyone, and no one should divide them into types and hope that a munition from a tank won't cause damage. Sappers don't recommend fishing or swimming in not-yet cleaned water bodies. However, after surveying the reservoirs, fishing may become safer.

Trostianets City

Tai, the sapper dog

The former brick factory's territory was on the city's outskirts. russians were based there during the occupation. Trostianets and Okhtyrka can be seen from here, as if at your fingertips. The entire territory and surrounding forest plantations were mined. There were tripwires everywhere, with which the russians tried to secure their presence during the occupation. After leaving, they mined almost the entire territory of the plant.

Since the territory's initial survey may not give a complete result, dogs come to the sappers' aid. Let's get to know dog trainer Maksym Patiokha and his assistant Tai.

"A mine can lie under a bag, a slate, anything—a dog can detect explosives thanks to its good smell. We put a marker and go on to work. Two dogs should mark each place."

Maksym and Tai are from the city of Romny, the interregional rapid response center. The man has been working there for 16 years. His assistant Tai is only three years old, and the staffers prepared the dog themselves. The dog works not only with Maksym but also with the second partner, taking turns.

"We start preparing a dog from three months of age, and it trains all its life," explains Maksym. "Malinois (Tai's breed, ed.) works very well, just like the German shepherd, but its temperament is more durable; it can work longer. Tai likes this kind of 'work'; it's like a game of hide-and-seek: someone has hidden it somewhere, and he has to find it. The dog is not looking for what I want but because he likes it. When he finds something, he either sits down, stands, lies, freezes, and looks only at the place where he smelled it."

We watch how Maksym and Tai work. The dog sniffs the building very briskly and curiously and freezes almost immediately.

While Tai and Maksym are moving on, at the place where Tai froze just a minute ago, another sapper pulls out a grenade from under the rubble. We watch the sappers take anti-tank mines and grenade launchers out of the house and put them in a specially designated place. They will soon bring them to the field to the detonation site.

We go inside the room. Maksym sighs:

"If I could cuss… It's not just a mess; it's everything. Where they ate, there… they did everything. These are not orcs; I don't know what word to choose"

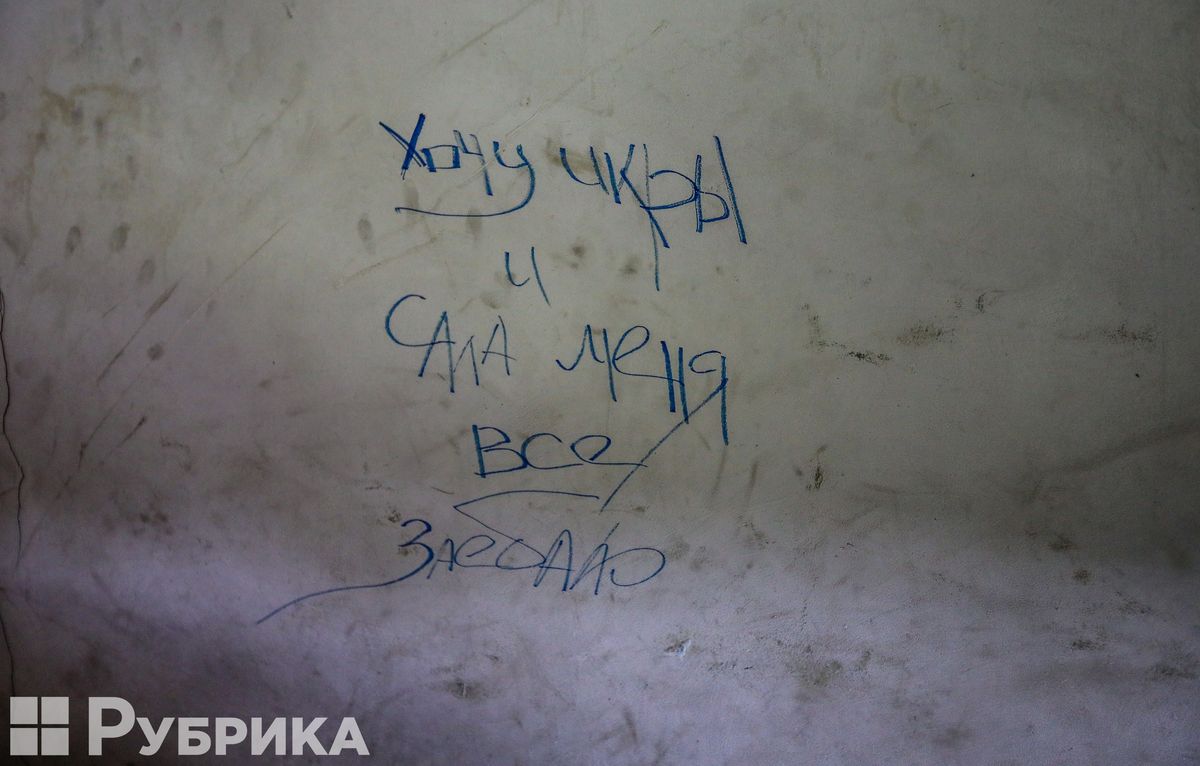

There's a terrible mess inside, everything is scattered, and some almost "rock" paintings are visible on the walls.

All doors are broken. On the floor, there are many empty candy boxes from the local confectionery factory; during the occupation, the invaders looted all the shops in the city.

Boholiubove Village

Time for our last stop. From afar, we are watching the detonation of the ammunition found today.

The area here is historical. Nearby is the village of Boholiubove, not far from which, in August 1399, a historic battle took place on the Vorskla River between the Golden Horde and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. This battle was one of the most massive and bloodiest battles of the Middle Ages.

Now there are entirely different battles going on here—fights with the consequences of occupation by russian troops, with barbarism in its purest form.