Before the war, Uliana was an architect who developed a family confectionery cafe and a flower shop— also a family business. "I'm both a florist and a pastry chef… That's 'too active' a person," she says.

Enemy military equipment reached Melitopol on the evening of February 24: "They entered the suburbs at 7 pm. Some brave men drove around the city district where there's an exit route to Crimea and asked soldiers, 'Why did you come here?' The russians launched the attack on the city, as all over Ukraine, at 5 am on February 24," our article's heroine says.

Then everything went per the scenario of the occupied cities: on February 25, the mobile service began to disappear, and then the russians bombed the tower; the town was left without any communication with the outside world:

"It was because the military drove russian equipment through Melitopol. The connection was turned off so that no one passed this data to the Armed Forces. They did that several times."

"National guardsmen" of Melitopol and tightening the screws

"The looting began almost immediately. The russian occupiers were the first to plunder, followed by the Melitopol residents themselves, whom we consider to be the marginalized group. Somewhere on February 26, local active men began to organize into militias. They had an 'educational conversation' with some of the looters, and they and the other marginals began to return the loot. They did all this on video: looters returned washing machines, refrigerators, and food and handed over the money. I believe it was a shock that caused this herd instinct and the lack of civilized behavior, but then it all started to roll back. The events took place at a cosmic speed, and everything changed every 3 hours. The store is still selling goods on one side of the street, and on the other side, it's already being robbed."

There was no time to form the official territorial defense, as it was in Kyiv, in Melitopol, but the mechanism worked properly: the militiamen kept order in the city. However, it did not last long.

"The russians began to persecute people with a pro-Ukrainian position who served in this territorial guard. Soon the russian occupiers banned the actions of our militias: they said it was illegal by their 'occupier' standards. The occupiers are present at every second intersection in the city. They go to our markets, picking apples with machine guns."

Uliana spent an entire month under the occupation, and she watched as the ruscists gradually tried to crush the local population:

"Until our mayor was kidnapped—it happened on March 11—there had been many people who openly expressed their position, even rushed to the tanks! On March 8, the first shots were fired at people at rallies, and then after March 15, the protests were banned. People began to be taken away into paddy wagons; people were locked in basements while the russians took others out of the city. We have a bunch of russian guardsmen—Chechens, Kadyrovites—we saw that these are not russian faces."

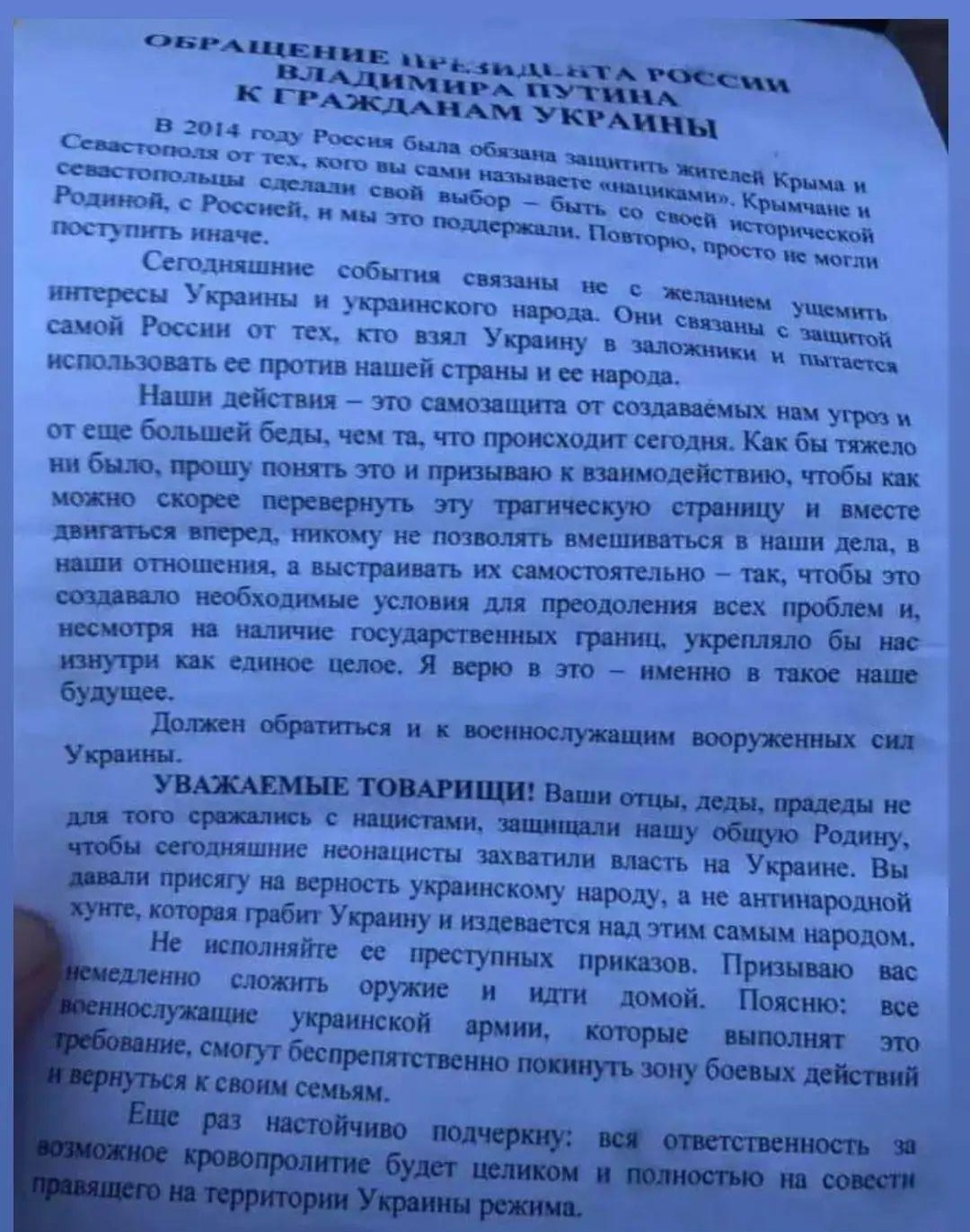

Instead, russian propaganda appeared. The city was isolated from information: All Ukrainian TV channels were switched off, radio was muted: "One day, I was driving my car and heard a radio broadcast by putin about how Ukraine ' blew up the entire heritage of the russian empire,' that he felt sorry for this and promised to restore it all."

"Where have you been for eight years" and other delusions

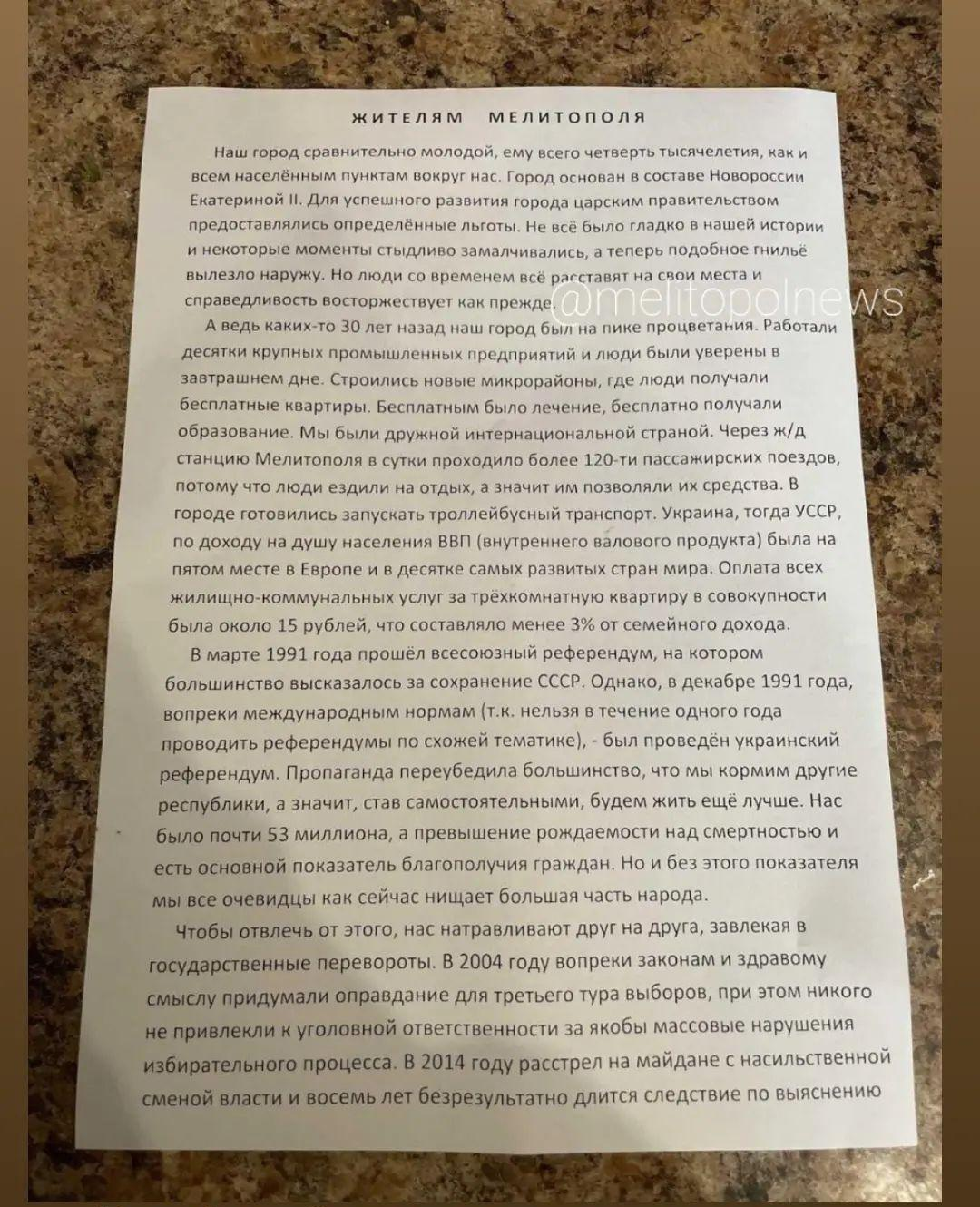

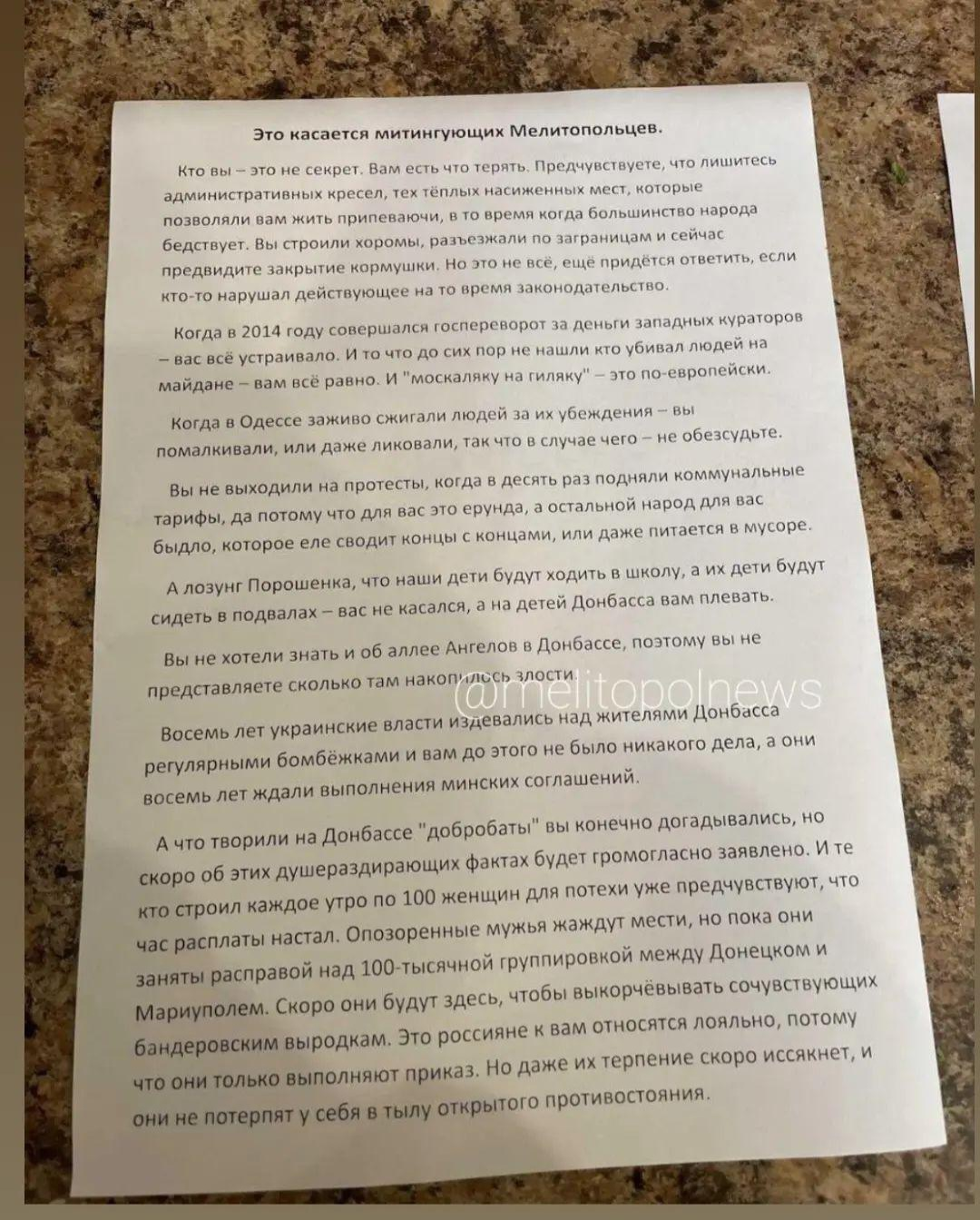

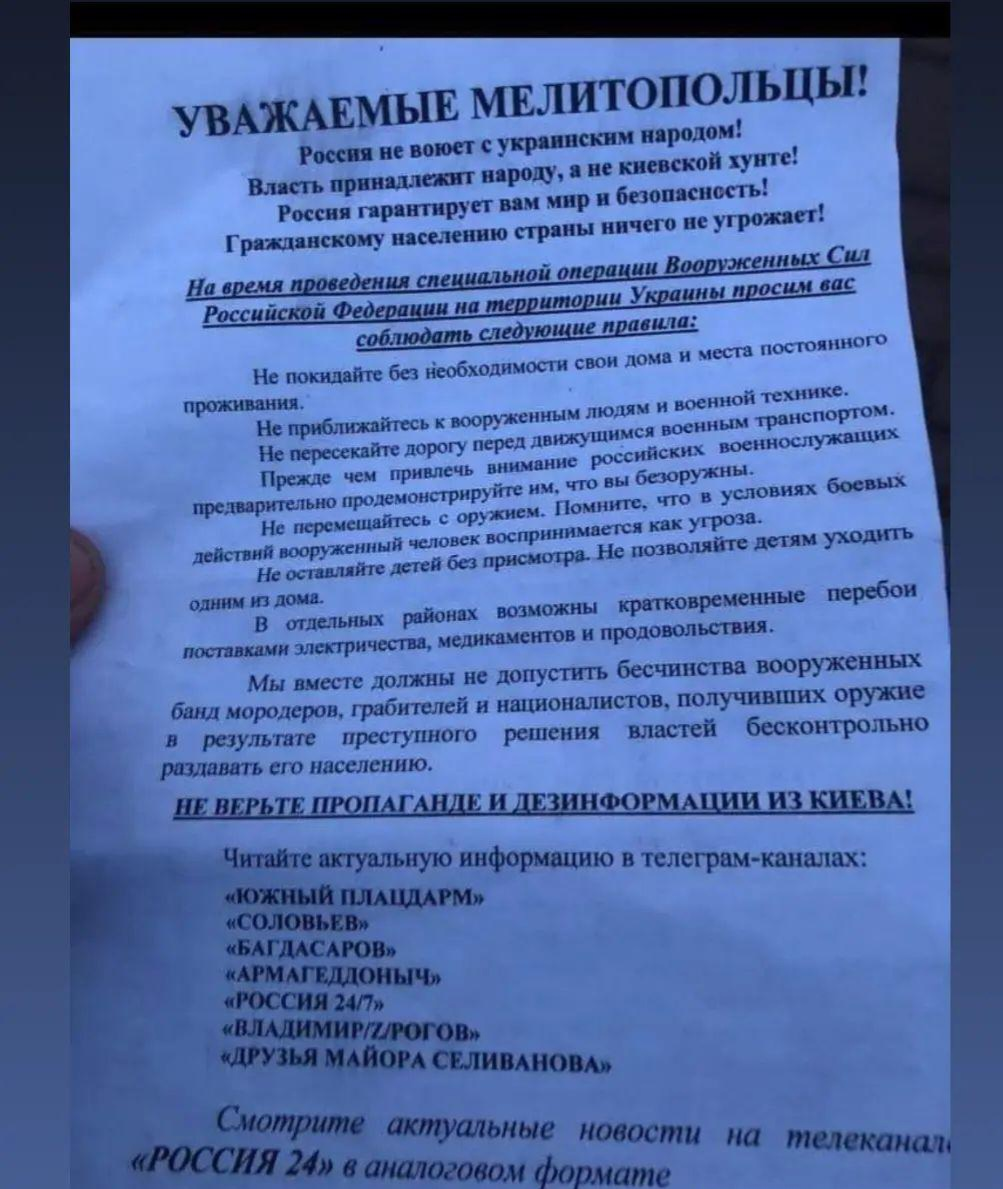

The russians did not invent anything new and turned to the old methods used by the German occupiers during World War II: they began to distribute leaflets. Uliana photographed the ones she came across: not even a newspaper, but a plain text printed on a sheet, saying how prosperous the city was 30 years ago, and "how the majority of the people are now impoverished," how "we are being set against each other, carrying out state coups" (legitimate elections in 2004), the "coup in 2014 for the money of western curators" and other delusions of russian propaganda, including the notorious "where have you been for eight years."

The locals kept the leaflets only to demonstrate how brazen and flat the enemy's lies could be.

There were also proposals for cooperation: the russians created their own people's militia. They said that holding rallies was illegal, advising us to stay at home and not go anywhere, not to provoke aggression, and not to attack russian soldiers. They urged "to demonstrate as much as possible that you are not dangerous to the russian military "… But then the abduction of people with some social influence began. I think these people were forced to cooperate. So they stole our head of the district administration, Serhii Prima."

The russian occupiers abducted Serhii Prima on March 13 after a search of his home. It is still unknown where he is now; more than a month has passed since his disappearance.

Humanitarian aid sold for money

Trucks with medicines and provisions were no longer allowed to enter the occupied city: we had to rely only on what was left in Melitopol from the "pre-war" period. It does not mean that the city was left without humanitarian aid; food, medicine, and other humanitarian assistance went from unoccupied Ukraine to Melitopol, but the occupiers decided to profit from the selflessness of the people:

"The self-proclaimed acting mayor closed the buses with humanitarian goods in the fire department. Now these products, supposed to become humanitarian aid, are being sold to people at space prices."

Instead of Ukrainian humanitarian aid, the russians brought their own. But since not many people took food from the hands of the occupiers, the russians had to stage a play: "The russians brought their humanitarian aid, but I saw five buses with people from Crimea brought in with them. They staged a theatrical performance where people from those buses took humanitarian aid. All this was filmed for television, but there was no single Melitopol resident in the lines. None of our acquaintances were there; we later discussed it. The person who organized it is now lying wounded in a Ukrainian hospital; our people are treating her."

The escape from Melitopol

Uliana's mother has cancer, and her last course of chemotherapy was in Melitopol. But she needs targeted chemotherapy; she gets IV all her life, one time in 3 weeks. The daughter could not obtain the necessary medicines in the occupied Melitopol. For her mother to continue treatment, it was essential to pass tests and perform CT scans. Because of the war, it also became impossible. The family decided to go to Zaporizhzhia and find a way to do it safely:

"We have a volunteer, Liubyshko. If you can mention him, be sure to do it. He's a great person; I don't know how he does it. He created Viber groups where people cooperate and manage to evacuate on safe routes, developed by him. They leave without a humanitarian convoy because it is dangerous to go with it; we understood this from the example of Mariupol. Yes, someone left once, but about 50 cars leave Melitopol every day, and all of them are crammed in with at least five people. You can count how many people leave the city, and still, many people want to. But people are afraid to leave because there are no guarantees, and you are responsible for yourself. As we were leaving, the russians shot our column after we crossed the border between the occupied and Ukrainian territories."

While Ulyana's family was on their way to Zaporizhzhia, there were nine russian checkpoints on their way, and the occupiers inspected them at each: "There was no aggression against me, but there was no doubt that they could shoot me. They checked the documents, looked at things in the trunk, and checked phones and laptops. Some men leaving Melitopol were asked to undress. At one of the checkpoints, we were asked: 'What do you think about the Armed Forces of Ukraine?' Not to provoke them, we said that we were leaving for treatment. Later he asked whether we were going to Poland. I think he asked it with a fit of slight jealousy. After all, there is already no prospect of any trips abroad for them," the woman jokes.

To date, 58 people have been abducted by russians in Melitopol.

The occupiers stole three million hryvnias from the Ukrainian post office; this money was intended to pay pensions, social benefits, and salaries to Melitopol residents.

They pass the call-up papers to the men of military age.

But there is also good news: a partisan movement is rising in Melitopol, and they have already fought 70 russian occupiers.

Everything will be Ukraine.

Melitopol is Ukraine!