What is the problem?

With the beginning of the full-scale Russian invasion, many citizens of Ukraine, who before the war exclusively spoke Russian, began to switch to Ukrainian. The interest in the language and the desire to break ties with the aggressor have grown in Ukraine and abroad. If earlier, many in the Ukrainian diaspora attended Ukrainian courses, now those hosting Ukrainians in their homes — doctors, volunteers, students, and scientists now want to speak the same language as those bravely fighting against Russian aggression.

What is the solution?

Inna Sopronchuk, from Kherson, in Ukraine's south, has taught Ukrainian as a foreign language for seven years. In 2022, she launched a language course for full-time students at the University of Oxford and her own school, "Speak Ukrainian." Rubryka spoke to Sopronchuk about how the most famous university in Great Britain introduced a Ukrainian course, and why foreigners are signing up to attend it.

How does it work?

Do what you like

Inna Sopronchuk originally comes from Kherson, Ukraine's southern city

In 2016, the idea of teaching Ukrainian abroad seemed surreal to Sopronchuk – much less Oxford. At that time, she was completing her master's degree at the Kherson National Technical University, majoring in English Philology, and was looking for a job.

Sopronchuk was looking for extra income in her student years, so in 2015, she started working as an English teacher in a private school and as a tutor. She soon realized that going to students' homes took a lot of time, so she switched to an online format.

Sopronchuk registered on an international platform for tutors to teach English to Ukrainians, but saw an option for teaching Ukrainian to foreigners — so she decided to give it a try. Requests from foreigners started coming almost immediately, and soon Sopronchuk started teaching an Italian who wanted to be able to speak with a Ukrainian friend in their native language.

Later, students from Norway, Canada, the USA, and Australia signed up for her classes. Most of them studied Ukrainian because they had a boyfriend or girlfriend from Ukraine, wanted to travel there, or had grandparents who emigrated from Ukraine long ago. The teacher says that at that time, she was very surprised that people who had never even seen their distant Ukrainian ancestors had the desire to preserve their roots — it was very inspiring.

"After graduation, I tried to find, as my mother used to say, a "normal job." She believed that online work was not serious," Sopronchuk recalls.

Sopronchuk thought she would go to work as a teacher at school or offices, like most of her peers. She tried to work in an office, but soon realized it was not her cup of tea.

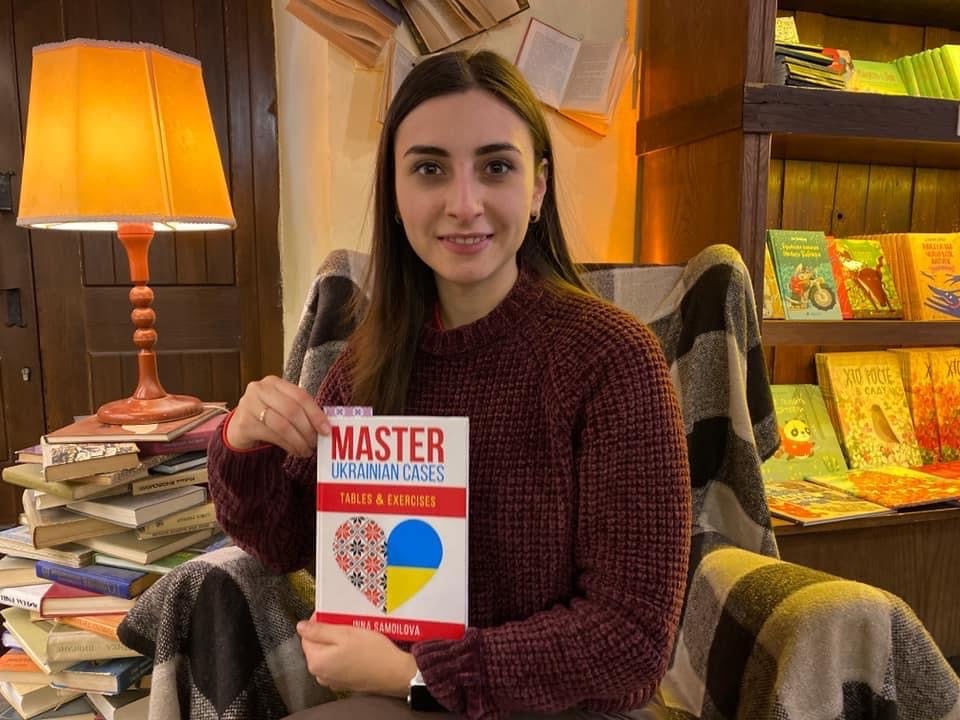

The teacher developed a big base of materials facilitating the language-learning process, including a textbook and language cards

Sopronchuk continued to do what she enjoyed. Expanding on her work as a tutor, she started recording videos on YouTube about Ukrainian culture and traditions, maintaining thematic pages on social networks. The next step was the creation of a small website with her own work — by that time, she had developed a base of educational materials for learning the Ukrainian language: a textbook, "Master Ukrainian Cases," three sets of language cards for learning 500 Ukrainian words, podcasts, had several hundreds of video lessons on YouTube and Instagram, and found like-minded teachers.

A Kherson student's desire to be independent turned into a full-fledged online school, called "Speak Ukrainian," where Inna and her team taught Ukrainian to foreigners. In total, more than 800 people from 28 countries of the world signed up for Sopronchuk's course.

Everything related to Russia is toxic

The war was a shock for Kherson. For two weeks after Russian troops entered the city, Sopronchuk hid in the basement before moving to a safer apartment, where she could no longer sit idly by, and continued holding classes at the online school. According to Sopronchuk, the war sharply increased the interest of foreigners in everything Ukrainian, including the language.

Students became more interested in Ukrainian culture, wrote letters to discover the truth about what was happening, and wanted to support Ukrainians. Sopronchuk shares that many foreigners who previously studied Russian now prefer to abandon it and switch to Ukrainian. They said that they don't need Russian now. With the beginning of the full-scale war, the Russian language ceased to be the "language of great culture," as it was sometimes called, and it became less prestigious to study it.

"The scariest thing about the occupation was that I continued to teach the Ukrainian language, tell students about the war, give interviews to foreign media, commenting on the situation in Kherson. All this was very risky," says Sopronchuk. Her husband is in the military and has been in the Armed Forces since the beginning of the war — presenting grave risks if the occupying forces found her out.

At the end of March 2022, Sopronchuk managed to get to Ukraine-controlled territory and went to live with her husband's relatives in Ternopil in Ukraine's west.

Everyone who knocks will have the door opened

Sopronchuk started a Ukrainian language course at Oxford

In the fall of 2022, she decided to move to Great Britain and try to offer her services to local educational institutions in order to popularize Ukrainian abroad.

Sopronchuk wrote, in her words, a "brazen letter" about herself, her school, and her achievements, and mailed it to universities in Britain with Slavic languages departments. Oxford responded to the teacher's letter, showing interest in the proposed course, and invited her to teach. Until then, Ukrainian as a foreign language had never been taught at Oxford, and the founder of the Speak Ukrainian school became a pioneer here.

Most of the British and European students currently taught by Sopronchuk at Oxford do not have Ukrainian roots. They study Ukrainian because their studies are related to Ukraine. For example, one of her students writes about the current situation with the Ukrainian church, and another writes about politics, analyzing relations between Ukraine and Poland. It is not just interesting for them to know Ukrainian, but also necessary.

"I still can't believe this is true and not a dream. I worked very hard for this. Thanks to my determination and perseverance, I am here now. I am sincerely proud and proudly bring my native language, history, and culture to the world," the Ukrainian teacher shares.

From extra-curricular course to Ukrainian studies

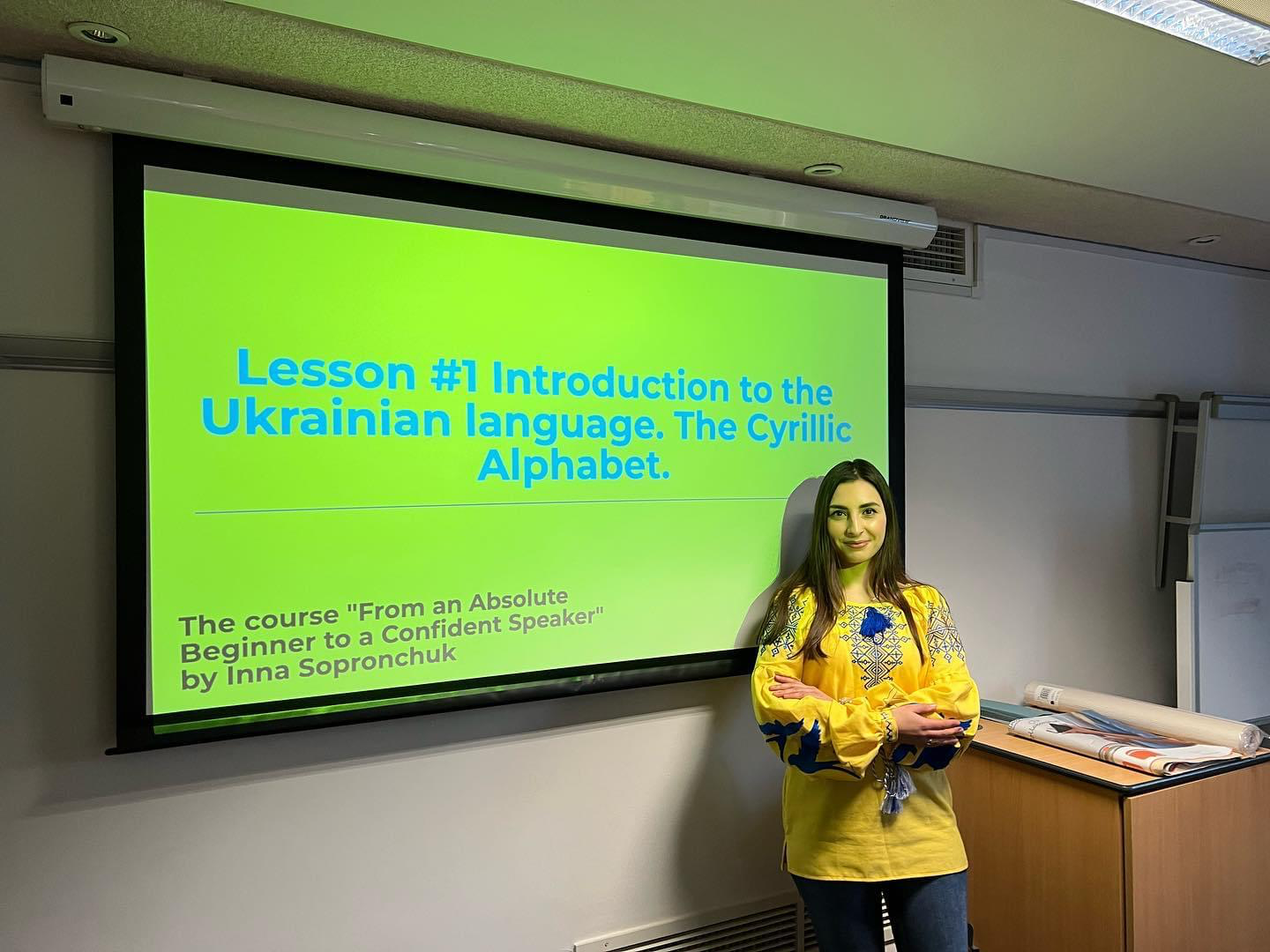

Sopronchuk teaching the basics of Ukrainian language

The Ukrainian course is being offered at Oxford for the second semester already. Currently, Sopronchuk has a group of six students. The teacher intends to convene other groups for students at an intermediate level and those who have studied the Ukrainian language before to form a whole department of Ukrainian studies, where there will be courses on Ukrainian history and culture.

Sopronchuk wants these courses to continue every semester so that students can learn constantly, improve their level and learn more about Ukraine. There have been Georgian and Belarusian programs at Oxford for many years, and the teacher shares that she considers it unfair that there are still no Ukrainian programs at Oxford but she is ready to do everything to make this dream come true.

While at Oxford, Sopronchuk found out that there were no Ukrainian textbooks at the university, and in general, in stores and libraries in Great Britain. Now she plans to fill the local library with materials for studying the Ukrainian language — and has already discussed this with the dean.

The faculty where she works is called Russian and East European Studies. The teacher says that seeing this name hurts her, and she wants to change it. Today, her minimum goal is to remove the word "Russian" from the name.

Not only about cases but also about Shevchenko and borscht

Oxford students reciting famous Ukrainian poet Taras Shevchenko's poems

"When I say that I teach Ukrainian as a foreign language, it does not mean that I teach only Ukrainian words, phrases, grammar," Sopronchuk shares. She teaches them about Ukrainian culture, and talks about what Ukraine is fighting for – reminding them that what is happening in Ukraine is not a "conflict," as it is sometimes referred to, but a terrible war. Her aim in this is to raise awareness of people in the world. In addition, when people who learn Ukrainian spread the language, it continues to live not only in Ukraine but also across the globe – which is important.

Most of Sopronchuk's full-time students studied Russian before the war, so, of course, they are very interested in history, politics, and philosophy. They know quite a lot about Ukraine, But the teacher tries to find something to surprise them with.

For example, "my students have heard about borscht, but not green borscht," Sopronchuk says with a smile – "this dish turned out to be very unusual for them, especially when I explained how it is cooked, that sorrel and boiled eggs should be added to it."

In one class focusing on words related to food Sopronchuk baked and brought cottage cheese pancakes to her students. The students had never tasted them before, and this gastronomic experience was exciting for them.

Oxford students are already making progress: to celebrate the birthday of Taras Shevchenko, Ukraine's most prominent poet, Sopronchuk recorded a video of students reciting his poetry. They are also proud that they (almost) managed to pronounce the Ukrainian word "palyanytsya" – which became a meme during the first months of full-scale war when Ukrainian soldiers used it as a test to discover undercover Russian spies, as its distinctly Ukrainian pronunciation makes it challenging for non-native speakers.

"I believe that what I am doing now is my life's mission," Sopronchuk says with confidence. "I popularize Ukrainian because I want Ukraine to win. I want our language to be heard everywhere so that people study it, love it, respect it so that it lives, continues to flourish, and takes its place among the most popular languages in the world."

Even more useful solutions!

Volunteer activity

Photo review of a charity shop "Buy a t-shirt, save Ukrainian life"

While in occupied Kherson, Sopronchuk not only continued to teach, but also created a charity shop, "Buy a t-shirt, save Ukrainian life."

As of today, the project has raised over $30,000. The teacher says the funds are directed to volunteer organizations that help the residents of her hometown with medicine and other humanitarian aid.

Sopronchuk visited Kherson in spring 2023

"I remember Kherson vividly – with kayaks, the sea, warmth, fresh fruit. I thought I was sleeping, and it was all a terrible dream," Sopronchuk says, sharing her impressions after a trip to her homeland in the spring of 2023. "Unfortunately, it is not a dream. The truth that not everyone understands and realizes, which many keep silent."

Sopronchuk believes that despite all the pain, the brave, patriotic, and unconquered Kherson people will rebuild the region even better than it was before.

For her part, Sopronchuk does everything to speed up the moment of Ukraine's victory. Her subscribers and students are actively contributing by donating funds. In winter, a caring Ukrainian ordered and sent 26 masonry stoves to Kherson people who were left without heating. Now she plans to buy equipment worth $5,000 for a maternity ward in Kherson.