What's the problem?

May 2023. Ukraine's western Ternopil region. A small group of friends is having drinks. One man begins boasting about having actual combat grenades. No one knows where he got them. Assuming the grenade he showed was just a dummy, his friends watch as he walks past the houses, crosses some gardens, and finally throws it into a nearby river to "prove" it is real.

The explosion was heard throughout the entire village, but thankfully, no one was hurt. Later, police searched the man's house but found no other grenades. His case has since been stalled for over a year.

Around the same time, another accident occurred in the eastern Kharkiv region. A soldier on leave brought home a piece of a grenade as a trophy — the detonator. No one was trying to prove it wasn't a dummy, but somehow it detonated on its own, injuring one person. A similar undetonated fragment was found in the soldier's house, and the investigation remains open.

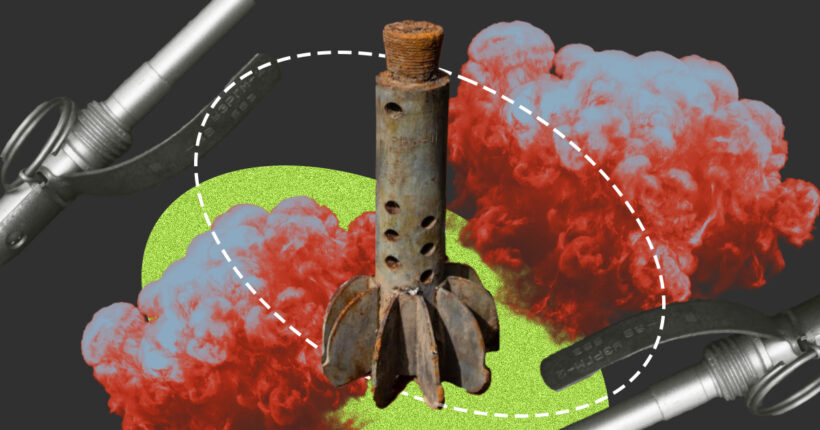

Photos of a grenade detonator. Source: internet

These are just a few examples of tragic incidents in a lengthy record. And they represent only cases where the explosive actually went off. How many others are waiting to "make their debut"?

"When I was working near Pokrovsk in the Donetsk region, a chaplain approached me with a stun grenade, saying, 'I wanted to throw it to prank the guys.' That joke could have ended tragically; it was a live fragmentation grenade from Belgium," says Major Serhii Senyk, an officer-psychologist with the Airborne Assault Forces Command.

Major Serhii Senyk, officer-psychologist with the Airborne Assault Forces Command. Photo from personal archive

Senyk explains that some explosive devices look almost "toy-like," which misleads even experienced soldiers — let alone civilians. What seems safe at first glance can end up causing severe injuries, disability, or even death.

According to the Main Directorate of Mine Action in Ukraine, Civil Protection and Environmental Safety, 1,052 people have been injured by explosives in recently liberated areas since the start of the full-scale war, and 311 were killed.

"The majority of accidents — 221 injuries — were due to unsafe handling of explosive items. There were also 188 injuries during farming activities, 145 while traveling, and 123 during household tasks," Oleksandr Riabtsev, a representative from the Mine Action Directorate, stated.

These numbers don't account for people injured or killed by detonations in relatively peaceful areas like Lviv or Ternopil.

Why are people drawn to potentially explosive "trophies"?

Whether it's an unexploded grenade found in a forest where Russian soldiers once camped or an artist-decorated shell casing bought as a keepsake, the impulse behind both is similar — we seek war trophies. These objects act as symbols, as if we've conquered something or taken part in something meaningful.

The real question is, how safe are the trophies we choose, and what do they represent to us? Nina Romanets, a practicing psychologist, explains:

"The so-called war trophy is something physical, something you can see and place as a reminder of what you've gone through. It's also a way to control something that once brought danger and fear."

Practicing psychologist Nina Romanets. Photo from personal archive

Romanets adds that the safety of the trophies we choose often depends on our knowledge of what's dangerous. Major Serhii Senyk agrees, noting that trophies aren't necessarily bad; for soldiers, they can even be a form of self-identity.

"Trophies are a significant part of a soldier's experience — a reminder of overcoming fear, defeating an enemy, and witnessing important events. In the war's early days, when equipment was scarce, even enemy boots were taken as trophies," says Senyk.

The military psychologist stresses the importance of distinguishing between trophies and looting. Actual trophies are weapons or personal items taken in battle, not things lying around to be stolen.

"But our mentality also plays a part in bringing home explosive trophies. There's a tendency to hide weapons or explosives 'just in case' for self-defense, or because 'nothing must go to waste,'" Senyk adds.

Nina Romanets says civilians and soldiers often have different motives for bringing home explosive items; sometimes, they aren't fully aware of these motivations.

"For soldiers, a trophy can symbolize personal or collective victory over the enemy. Despite their better understanding of these items' dangers, they might experience a shifted perception of risk when returning to civilian life," says the psychologist. "In contrast, civilians might do this out of curiosity or ignorance, while soldiers may feel less affected by danger."

Another reason for the increased number of explosives in Ukrainian homes is simply becoming accustomed to the presence of war and all its elements. People have grown used to the air raid sirens, and just as we ignore them, we also overlook warnings about other dangers.

At first, explosive items may frighten us, but over time, our protective instincts weaken to reduce the stress our bodies endure. Romanets refers to this as desensitization.

"The sense of danger is highly mobilizing but drains much personal energy. When this goes on for too long, our psyche has only one option — to reduce sensitivity and adjust," says the expert.

Illustrative photo from Rubryka

How can we address this issue?

Possession and carrying of explosive items or weapons can lead to imprisonment for up to seven years. If one of these trophies detonates and harms someone, the punishment may be even more severe.

The Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) and the Military Law Enforcement Service control the circulation of firearms and ammunition. They inspect vehicles at checkpoints exiting conflict zones. However, as Major Serhii Senyk explains, small explosive parts can still evade detection.

He explains that due to their small size, these items are often attached to soldiers' gear and transported unnoticed. This is especially true for foreign-made grenades, which usually look deceptively harmless and toy-like and have ignition systems unfamiliar to Ukrainian forces.

"Hand grenades and their compact fuses can be concealed on a soldier's gear and transported out of the area," Senyk says. "That's why incidents with handheld grenades, especially foreign-made ones, are most common. Their detonation systems differ from ours, and, at times, they resemble toys."

Senyk also emphasizes that while soldiers are educated on safety, they still lack the knowledge to fully understand the danger. He suggests that targeted social campaigns could effectively show the "grenade-at-home-tragic consequence" connection.

Ілюстративне фото "Рубрики"

Psychologist Nina Romanets agrees that emotionally impactful and clear messaging could also reach civilians inclined to keep a piece of ammunition at home.

"Stories of actual incidents and potential harm visualization are the most effective," Romanets says. "The messaging should be straightforward, focusing on the value of life and safety."

Nina Romanets stresses that Ukraine needs a comprehensive approach. Information campaigns should reach people of all ages and sectors. Promoting safety and caution around suspicious objects should become a modern trend. This could involve schools, social media, and mine safety training sessions.

How to talk to someone who has brought home an explosive Item

Romanets advises against accusing or creating conflict. Such a conversation may cause the person to become defensive and ignore even the most logical arguments.

A piece of ammunition. Illustrative photo by Rubryka

The psychologist suggests approaching the discussion calmly and highlighting the potential consequences for the family as a whole. Try to understand the person's motivation — is it for self-defense or a keepsake? Could it be replaced or made safe?

"It's essential to realize that people aren't disregarding reality out of ignorance. Sometimes, it's a coping mechanism. Support and understanding are key," Romanets explains.

Senyk agrees that persistence and prioritizing safety are crucial in such situations.

"Families need to firmly express their concerns," he says. "You can understand the desire to keep war memorabilia — for self-defense, for instance. However, under the law, explosive items are always seen as tools of aggression. Families should set conditions: either the items are voluntarily surrendered, or they'll contact authorities. This would lead to legal repercussions."

If you find an explosive item, call the police. If you or a family member brings one home, remember that voluntary surrender exempts you from criminal liability, as outlined in Part 3, Article 263 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine.