Ivan Bahrianyi: the voice of the Ukrainian nation and champion of freedom

Photo: Nadiika Pototska / Facebook

Escaping from torturers, being chased, hiding in the extreme conditions of Siberia, working in the underground, always carrying a cyanide capsule, writing dozens of works that helped bring down the USSR, and one piece that saved hundreds of thousands of Ukrainian lives from that same USSR. A Nobel Prize nomination.

It sounds like the plot of an action-packed James Bond movie or a superhero tale — but no, not yet. This is the real story of the incredible Ivan Bahrianyi, one of the top figures in mid-20th-century Ukrainian literature. Today, you can find his works in every bookstore and library in Ukraine. People tattoo his quotes on their bodies, and filmmakers dream of adapting his novels. But just 33 years ago, Bahrianyi's works were banned and unpublished in Ukraine.

I want to tell everyone about him, urging people to read his work and shout excerpts of his writing to the world, the way people once shouted hoarse, reciting his pamphlet Why I Am Not Going Back to the Soviet Union. Each of Bahrianyi's works is a vaccine against Russia — the kind the world so desperately needs. So, let's learn more and spread the word!

Childhood

Ivan Pavlovych Lozoviaha, which was the writer's real name, was born on October 2 (September 19 by the new calendar) in Okhtyrka, Poltava region (now Sumy region), into the family of a bricklayer. He described himself like this: "All my family on my father's side were bricklayers… By origin, I'm a Ukrainian, a real Ukrainian commoner." He had two sisters and a brother.

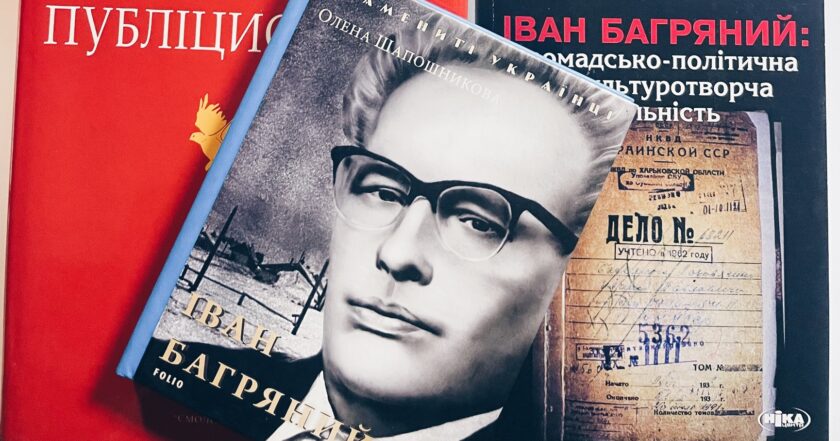

Photo from the book Ivan Bahrianyi: Socio-Political and Cultural Work

Even in school, Ivan started writing poetry, and his early work already had a spirit of protest. "I wrote my first poem when I was ten, in the first grade of the 'Primary School.' I wrote it in Ukrainian as a protest against the teacher who hit me on the head with a ruler because I couldn't speak Russian. Later, I could speak Russian, but I didn't want to," Bahrianyi recalled.

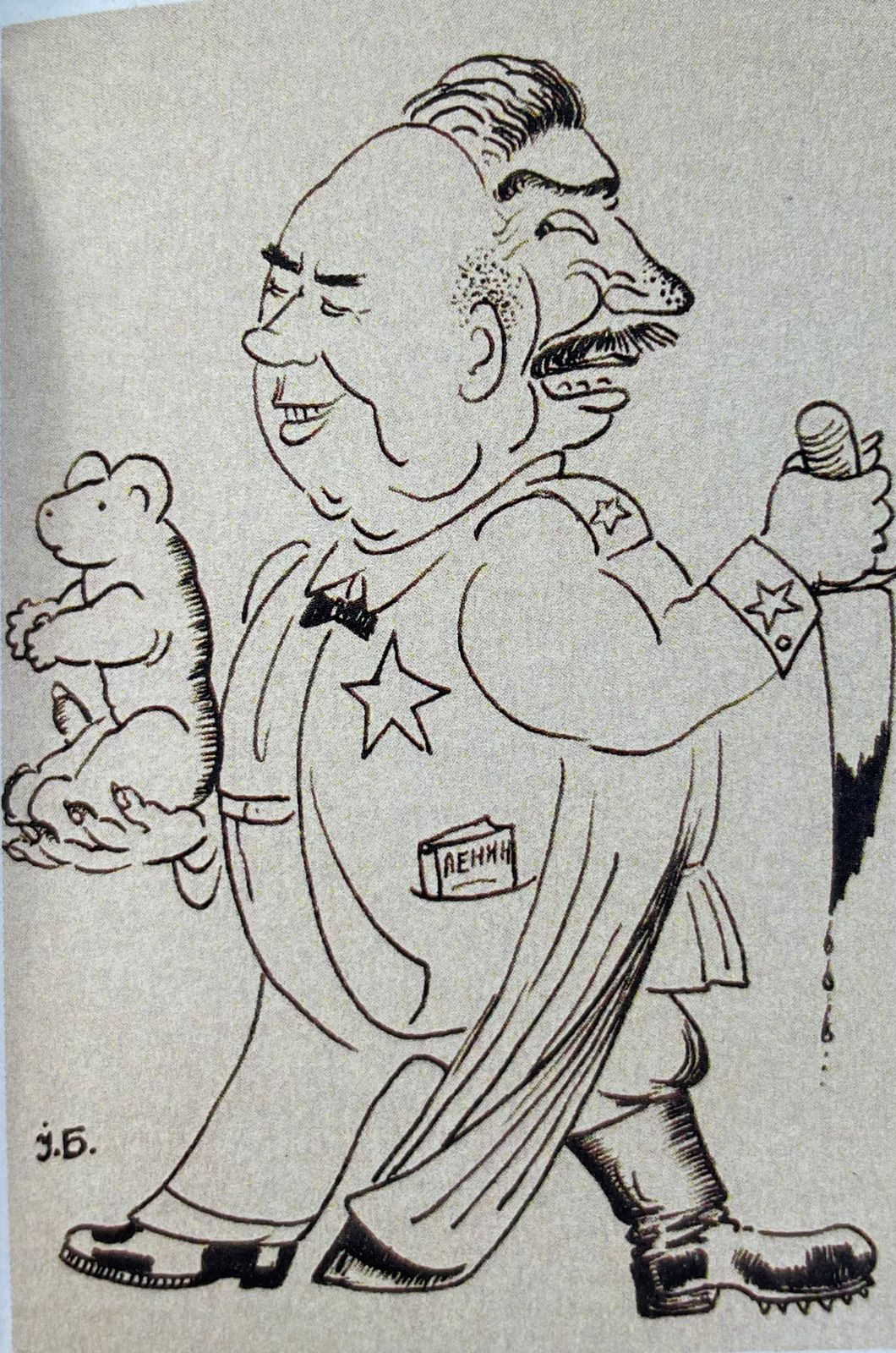

He also had a talent for drawing. Later, he would illustrate his own books and create postcards against the Soviets.

The crime of Soviet power

As a child, Ivan witnessed the cruelty of the Bolshevik regime: he saw his grandfather and uncle, a soldier of the Ukrainian People's Republic (UNR), brutally tortured and murdered. Here's how Bahrianyi described the event:

"I was just a 10-year-old boy when the Bolsheviks invaded my mind as a bloody nightmare, appearing as the executioners of my people. This was in 1920. At the time, I lived with my grandfather in a village on a beekeeping farm. My grandfather was 92 years old and had lost an arm. Then, one evening, some armed men speaking a foreign language came. Right in front of my eyes and those of my cousins, they tortured him to death while we screamed in terror. They also killed one of his sons — my uncle.

"They killed my grandfather because he was a wealthy Ukrainian farmer (he owned 40 hectares of land) and opposed 'the commune.' They killed my uncle because, during the national liberation struggle of 1917-18, he was a soldier in the Ukrainian National Republic Army. He fought for the freedom and independence of his people."

Note: There's a slight inconsistency in Bahrianyi's recollection here. He states he was ten, but by 1920, he would have been 14-15. Historians confirm that the event took place in 1920.

Student years: wanderings and early resistance

After school, Ivan Bahrianyi studied at a technical school to become a locksmith and at the Krasnopil Art and Ceramics School. He worked various jobs: teaching art at a colony for homeless children, serving as a political officer at a sugar factory, illustrating for a newspaper, and even working as a political inspector for the Okhtyrka police. He traveled widely — across Poltava, Crimea, Kuban, and Donbas.

In 1926, he enrolled in the Kyiv Art Institute, though he didn't graduate due to pressure from the authorities. In Kyiv, Bahrianyi immersed himself in the literary and political scene, joining the opposition literary group MARS (Workshop for Revolutionary Words). He befriended prominent figures such as Todos Osmachka, Valerian Pidmohylnyi, Yevhen Pluzhnyk, Borys Antonenko-Davydovych, and Hryhorii Kosynka. It was also in 1926 that he began publishing under the pseudonym Ivan Bahrianyi.

In 1929, he released a collection of poems titled To Forbidden Boundaries. He later published the poem Ave Maria and the novel in verse Skelka. His works already carried a strong anti-Soviet stance, which attracted the attention and pressure of the authorities.

On January 22, 1930, at the All-Ukrainian Congress of Komsomol Writers Molodniak, his works were labeled as "trash" and "waste paper." Bahrianyi was publicly accused of "smuggling ideas hostile to our era" into his creative works. In 1931, a scathing article titled Along the Kulak Path: On the Work of Bahrianyi was published, where he was accused of being "a singer of Kurlak ideology" — Kulak being the term which was used to describe wealthy farmers or landowners.

Arrests. Many arrests

On April 16, 1932, 25-year-old Ivan Bahrianyi was arrested. Before this, he had been threatened, persecuted, and physically tortured for confessions. After six months in prison, he was released on October 25, 1932, and was banned from living in Ukraine for three years. Officially, he was sent to a "free settlement in the Far East" — the Khabarovsk region near the Bering Strait. In reality, this was exile to hard labor.

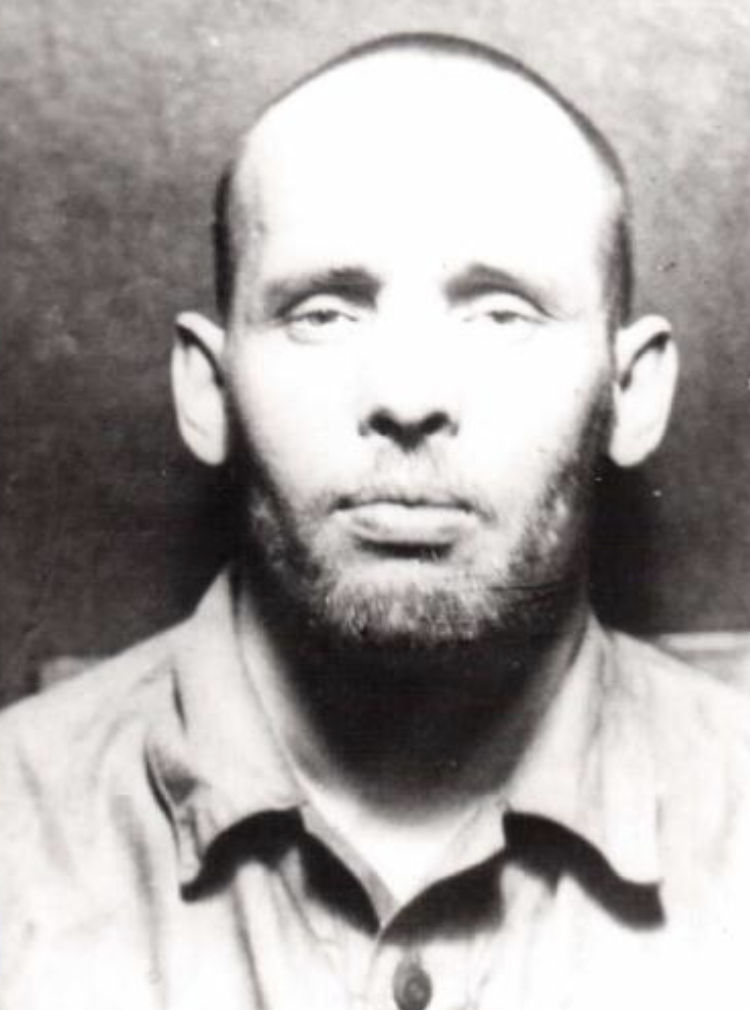

Ivan Bahrianyi during his first arrest by the Soviet authorities. Materials from the archive of Oleksandr Shuhai.

From there, Bahrianyi escaped. He hid among the Ukrainian community in the Green Ukraine, a would-be independent Ukrainian state in the southern Russian Far East. "It's better to die running than to live rotting," he later wrote in his novel Tiger Trappers (published in English as "The Hunters and the Hunted") about this experience. During this time, he met his first wife, Antonina Zosymova. In 1936, they had a son, Borys. The family would never have even one year of peace.

In 1938, after returning home, Bahrianyi faced new charges: participating in an anti-Soviet uprising organized by anarchists and engaging in anti-Soviet activities. Again, he endured threats, torture, and inhumane treatment. Despite the terror, pressure, and physical abuse, the writer refused to sign the confession. He was later released. In the April 1, 1940 decree, it was noted that all evidence of counter-revolutionary activity belonged to past years, for which he had already been convicted, and "no other information about Bahrianyi-Lozoviaha's anti-Soviet activities was obtained during the investigation."

War and a new life

When the war began, Bahrianyi worked as an artist at the Okhtyrka theater "Narodnyi Dim." In 1942, he was arrested again, this time for the anti-fascist message of the theater's curtain design. He spent two months in prison but managed to escape. He then joined the Ukrainian underground and moved to western Ukraine.

During this time, Bahrianyi said goodbye to his family for good. His son Borys would face a challenging future. He would even take his mother's surname, but it didn't help. He wasn't allowed to take entrance exams at Kharkiv University, where he had planned to study, or at any other educational institution.

Bahrianyi's son, Borys, would become one of his greatest adversaries. First, under pressure from Soviet authorities, and later, even during independent Ukraine, he criticized his father. In 2006, he said: "I don't have any favorite works of Ivan Bahrianyi because I haven't read them. I don't share his views, and I don't understand why people make such a fuss about him. I support a national Ukraine, but not the bourgeois-nationalist Ukraine that Ivan Bahrianyi advocated."

But let's go back to the early 1940s. Bahrianyi worked in the propaganda department, writing patriotic songs and various articles and drawing caricatures and posters for agitation. He also contributed to the formation of the Ukrainian Supreme Liberation Council (UHVR), helping to draft its key documents. In 1944, he wrote one of his most powerful works, the novel Trappers (later known as Tiger Trappers).

After the war: "Why I Am Not Going Back to Soviet Union"

When Soviet troops began approaching the location of the UHVR, its members fled to Croatia. In the fall of 1945, Bahrianyi moved to a displaced persons camp in Neu-Ulm, Germany.

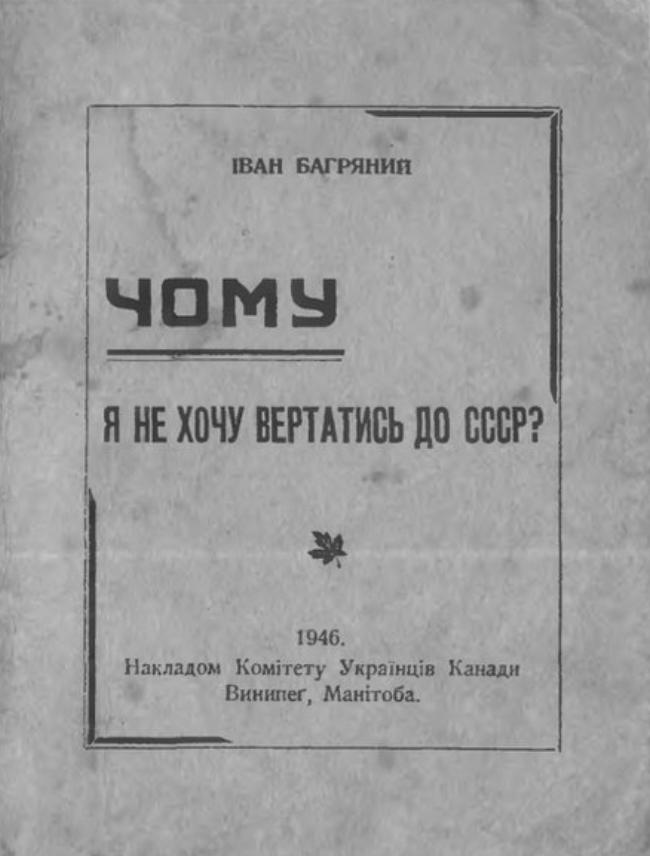

Under an agreement between the USSR and the Allied countries after World War II, people who had been citizens of Soviet republics in 1939 were to return home. Soviet repatriation commissions hunted down Ukrainians in DP camps, forcibly returning them "home." During this time, Bahrianyi quickly wrote the pamphlet Why I Am Not Going Back to the Soviet Union overnight.

He handed the pamphlet to members of the repatriation commission. According to a translator present at the time, Bahrianyi said, "Here's your answer! For all Ukrainians. Stalin and Hitler tortured us. And now you are threatening us again, saying we must return to the 'motherland.' Stalin will take his revenge on us as traitors."

In the pamphlet, Bahrianyi detailed the Soviet regime's crimes: labor camps, famine, forced collectivization, and murders. He explained that those sent back to the USSR would face the same fate. The pamphlet became the voice of the nation, as well as a protective talisman. People carried it with them, shared it with foreigners, and quoted it in meetings.

Bahrianyi's pamphlet was even used by Eleanor Roosevelt, the wife of the US president, in her reports as she advocated for human rights, including those forced to return to the USSR. In 1948, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which guaranteed freedom of movement and the right to seek asylum from persecution in other countries under Article 13. This saved the lives of hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians.

Bahrianyi was involved in organizing the Ukrainian émigré writers' group known as the Ukrainian Art Movement (MUR). He became one of the most important postwar Ukrainian writers. MUR was active for three years, publishing more than 1,200 books in the displaced persons camps. Hundreds of materials were written advocating for the Ukrainian people, and world authors' works were translated.

Photo from the book Ivan Bahrianyi: Socio-political and Cultural Work

In 1948, Bahrianyi founded the Ukrainian Revolutionary Democratic Party (URDP) and later became the editor of the newspaper Ukrainsky Visti (Ukrainian News). In 1963, the Union of Democratic Ukrainian Youth (ODUM) in Chicago launched a campaign to nominate Bahrianyi for the Nobel Prize in Literature. However, their plans were interrupted by the writer's sudden death. Scholars believe that Bahrianyi had a real chance at the Nobel Prize. He was the first to write novels about the GULAG, nearly twenty years before Solzhenitsyn's The Gulag Archipelago, which won the Nobel Prize.

In his later years, Bahrianyi suffered from severe illnesses as a result of his time in Soviet prisons. He had heart disease, tuberculosis, diabetes, and other ailments. Yet, even in his most difficult days, he continued to write, using a portable typewriter on his chest as he lay in bed. He died on August 25, 1963, and was buried in Neu-Ulm, Germany.

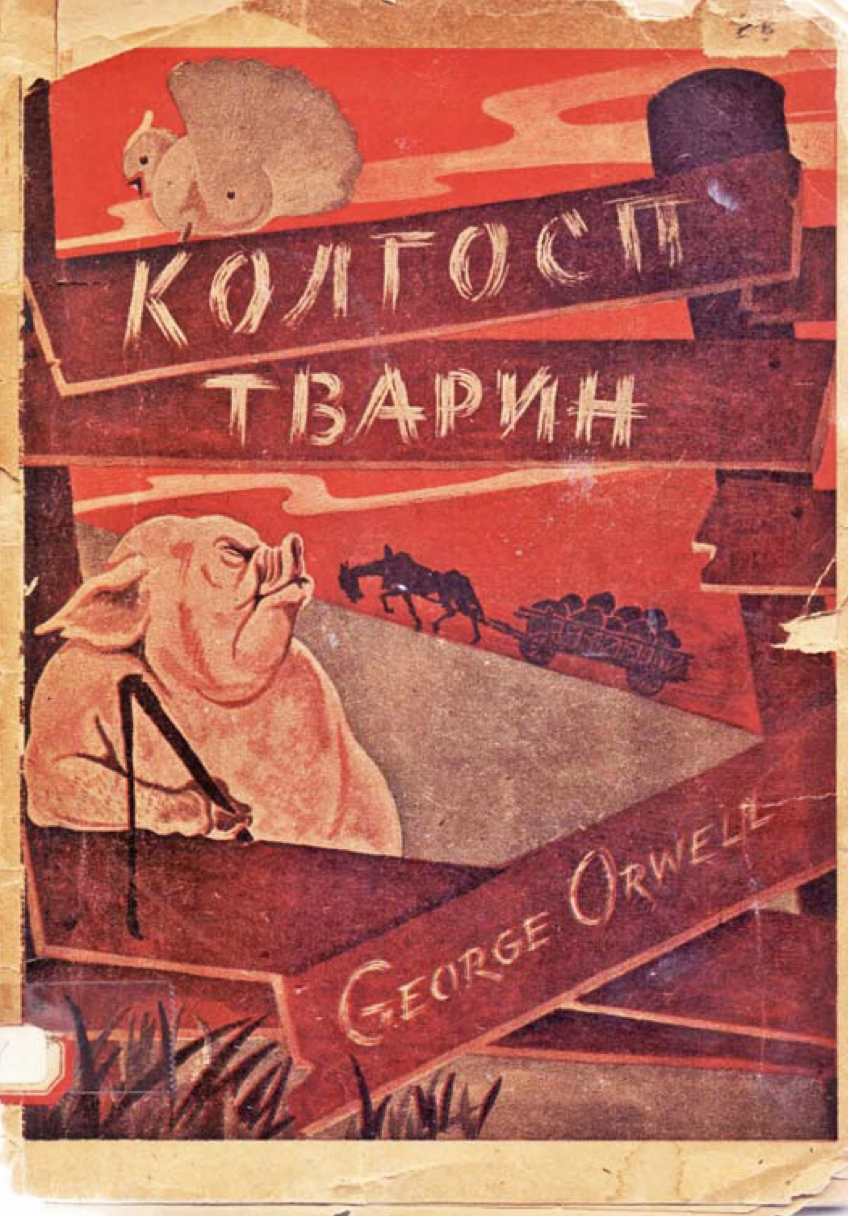

How Ukrainians funded the first translation of Animal Farm

One of the first translations of George Orwell's Animal Farm was the Ukrainian version, Kolhosp Tvaryn, with an original preface. It was translated by Ihor Shevchenko (under the pseudonym Ivan Cherniatynskyi) and published by Prometheus Publishing, which was associated with the newspaper Ukrainian News, where Ivan Bahrianyi was the editor-in-chief.

Funds for the publication were allocated from the contributions of Bahrianyi-founded party members. There are also speculations that Orwell himself may have been one of the investors in the book's printing. Moreover, Orwell waived his fee for the translation.

The book deeply angered the Soviet authorities. It was one of the critical blows against the USSR and remains a tool in the fight against dictators and criminals today.

The first Ukrainian edition of Animal Farm, taken from the Universum magazine article "How Ivan Bahrianyi Supported… Orwell"

Bahrianyi's legacy: What to read

Before Ukraine's independence declaration in 1991, Bahrianyi was banned in his homeland. His works have only been accessible to Ukrainians for 33 years and remain underrepresented in school and university curricula. As a nation, Ukrainians have much to catch up on Bahrianyi.

Both Ukrainians and foreigners should start with his famous pamphlet Why I Am Not Going Back to Soviet Union. It remains relevant today and provides an essential message to the world. The text of the pamphlet is freely available.

Tiger Trappers is one of Bahrianyi's key works and one of the most powerful adventure novels of the 20th century. It's also a story about Soviet crimes, but more importantly, it contains a victory of good over evil. This ray of hope is something we all need. The book can be understood and appreciated by both adults and teenagers.

Along with Tiger Trappers, The Garden of Gethsemane is considered one of Bahrianyi's most powerful works. It's a manifesto of human dignity and a condemnation of the Soviet system. The novel portrays the horrific crimes of totalitarianism. While morally complex and perhaps too difficult for teenagers, it's a must-read for adults.

Publitsystyka ("Opinion Journalism") is a collection of articles, pamphlets, and other materials from 1946 to 1963. These sharp critiques of the Soviet regime and its atrocities are filled with precise comparisons, vivid descriptions, and historical examples. The collection is still useful today in the fight against Russian aggression.

Other important works to read include Man Runs Over the Abyss, The Fiery Circle, and Marusia Bohuslavka.

If you want to learn more about Ivan Bahrianyi's life, the following books may help:

This article uses information from the following sources:

- The Adventures of Ukrainian Literature book;

- Local History article;

- Ivan Bahrianyi by Olena Shaposhnykova;

- The Living: Understanding Ukrainian Literature;

- Oleksandr Shuhai's article How Ivan Bahrianyi Cared… for Orwell;

- Tiger Trappers;

- The Garden of Gethsemane;

- The pamphlet Why I Am Not Coming Back to the Soviet Union;

- Ivan Bahrianyi: Socio-Political and Cultural Work.