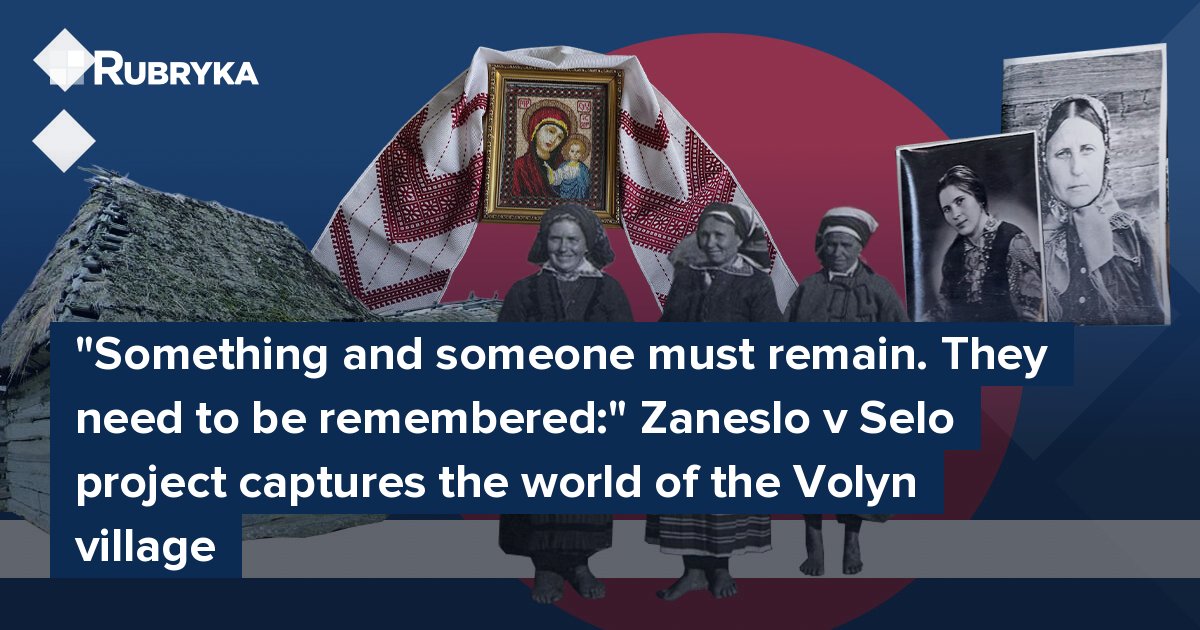

These stories are not only about traditions, long-forgotten recipes, or faded towels. They are about defeats and victories, past and present, about everything that people in the villages live with now. Rubyka shares how these stories are recorded.

What is the problem?

Villages are born and die. It is a part of life and Ukraine's history. However, to save their memory, to reflect and show them to the world means to preserve and strengthen one's own identity. To do this, you must go to remote corners of Ukrainian regions, seek an approach to local people and immerse yourself in archives. Not everyone will do it, but those who do it definitely love this with all their heart.

One day journalist from Lutsk Olena Livytska and photographer Ludmyla Gerasimyuk unexpectedly occurred in the village. Rubryka asked them how it happened and why.

"In old photos, everyone is young." Family photos from the house of 93-year-old Vera Korets, Khotsun, Volyn. Photo by Lyudmila Gerasimyuk

What is the solution?

"I carry many rural stories in me"

Olena Livytska. Photo by Lyudmila Gerasimyuk

The Zaneslo v Selo project arose in 2018 after the closure of Olena Livitska's column in one of the Volyn media. Then the publishing team moved on to another project, and the column with longreads about Volyn villages became irrelevant.

Livitska was very sorry that now she had nowhere to tell about the villages. Once, in a conversation with her colleagues, she was advised to start a page with that name and write there. This is how the project got a new life, but now — on social networks.

In Volyn, crosses in cemeteries are decorated with embroidered aprons and rushnyky — traditional Ukrainian embroidered cloth. Photo by Lyudmyla Gerasymiuk"I saw and photographed old crosses at the cemetery in the village of Lyubyaz, which are tied with embroidered aprons like on the throne in the church. I wrote about these aprons, and it started from that," Livitska says.

In Volyn, crosses in cemeteries are decorated with embroidered aprons and rushnyky — traditional Ukrainian embroidered cloth. Photo by Lyudmyla Gerasymiuk"I saw and photographed old crosses at the cemetery in the village of Lyubyaz, which are tied with embroidered aprons like on the throne in the church. I wrote about these aprons, and it started from that," Livitska says.

For her, the village is not just a project but a part of life. When she was very young, she grew up in the village with her grandma, and her parents lived in the city. Although Livitska later moved to the city, she returned to the village at the first opportunity.

A yard in the village of Sviichiv. Photo by Lyudmila Gerasimyuk

"It was an ordinary village, an old house with jasmine growing under the window, the cow's name written on the barn, and bread delivered twice a week," Livitska recalls. "You could buy carbonated water and exchange it for empty bottles. My grandfather sometimes took me to the farm with him, my grandmother cooked borscht outside in the summer, and there was a frame with photos of strange and unknown people in the corner. There was nothing special, and when you were alone, you were bored and looked around for something interesting. You looked, memorized, and discovered. Probably, that's how my interest in the details of this life grew."

This curiosity was the beginning of the stories that the journalist now collects, carries, and shares with the readers of her page.

"We don't plan, we don't count, we choose with our hearts"

A house in the village of Hotsun. Photo by Lyudmila Gerasimyuk

Currently, the Zaneslo v selo project is done by two people — Olena Livytska notices, listens, and writes, and Lyudmila Gerasimyuk takes photographs.

"Actually, it's really cool to find a photographer who sees the world as you do and who really wants to document it all. Just so that someone else will see it someday," says Livitska.

The project's goal is to capture the world of the Volyn village, to give an opportunity to feel and try it — for taste, smell, and color, and pass all this on to future generations. Where to go next time, the researchers do not plan in advance. They say they choose with the heart.

A house in the village of Buzaky. Photo by Lyudmila Gerasimyuk

"We have a lot of jokes about how we choose the villages for the trip. Once we filmed a video where the Cat Man walks around the map and chooses: where it stops — we go," laughs Livitska. "Actually, it is a little like that. We choose spontaneously. We don't explore from village to village, and we don't count them — we go to different corners of the same region because Volyn in Lyubeshiv region and Volyn in Horohiv region, for example, are different. There is Polissia, closer to Brest than to Lutsk. It is important for us to show Volyn in all its variety."

Toboly village, Volyn. Photo by Lyudmila Gerasimyuk

Anyone who thinks these trips are romantic is wrong. People often ask journalists to go with them. Livitska says that although she promises to take them with her, sometimes she refuses when she realizes that the trip can disappoint people because traveling is often a nervous and tiring affair. It is difficult and not always comfortable, especially if it is raining, snowing, or the people are unfriendly.

"No one stands at the door and waits for you to enter his house with a camera and start taking pictures of some windows, doors, and curtains on them or a frame in a corner on the wall. People have a life. If you ask: 'What are you interested in?' most likely, you will be told: 'Nothing. All the old-timers have already died. All the young people left. There is nothing to see here,'" the journalist shares.

The old church in the village of Melnytsia. Photo by Lyudmila GerasimyukResearchers hear this occasionally, but they do not give up, even when they encounter a misunderstanding of the project's purpose from the local authorities. However, there are few of them. Some community heads love Zaneslo v selo and help in every way. Sometimes they even offer to cover fuel costs in exchange for the researchers simply looking for something interesting in the community's villages and telling Ukrainians about it.

The old church in the village of Melnytsia. Photo by Lyudmila GerasimyukResearchers hear this occasionally, but they do not give up, even when they encounter a misunderstanding of the project's purpose from the local authorities. However, there are few of them. Some community heads love Zaneslo v selo and help in every way. Sometimes they even offer to cover fuel costs in exchange for the researchers simply looking for something interesting in the community's villages and telling Ukrainians about it.

"It's cool when they see value in something like this," says Livitska. "To be honest, we rarely turn to the authorities. I like to go away from people the most. For example, you pick up a postwoman on the road. She tells you about an older woman and leads you to another one… Or people drive cows to the pasture — you park the car under the church and follow them in line: one pulls up, the other, in a little while, and you already have a number of addresses and a number of impressions".

Pumpkins in the village of Velymche. Photo by Lyudmila Gerasimyuk

In such relaxed travel conversations, you can hear how the daughter of a local man convicted of a pogrom against Poles tells about how all the children in the village were afraid of her father, except her. Or how to cook hamula from apples.

Eat, pray, love

Olena Livшtska talks to a resident of the village of Poromiv. Photo by Lyudmila Gerasimyuk

To get all this, it is important to gain trust. The concept that everyone is obliged to tell and show something to visiting guests and journalists does not work here. Livitska says: simplicity and sincerity always help, and then real treasures are revealed to you. Authenticity in Volyn villages is not always about something in the past — it is present at every step today.

In one village, you will be told about black borscht, which is prepared with the blood of a freshly slaughtered pig. Or about bikus, which is actually a ritual soup for butchers made from fresh entrails. Rushnyk "from thunder". Photo by Lyudmila Gerasimyuk

Rushnyk "from thunder". Photo by Lyudmila Gerasimyuk

In another, they will tell about how tires are burned on Easter (and once, instead of them, big bonfires were lit from wood), and why they keep a towel embroidered and consecrated on Easter night on the hall doors — because it protects against thunder.

Or how "the feet of the dead are warmed" on the third day of Easter. This is how the tradition of commemorating ancestors is called in Smidyn in Volyn. Sounds creepy, but in fact, it is a feast around memories. They gather in the yard of one of the neighbors, be sure to bring firewood, food, make fires and sit around. They talk about dead relatives, remember, and eat.

Impressive stories about childbirth in post-war times. The woman gave birth on a special wooden table between the stove and the house wall, under which potatoes or other vegetables could be stored. They gave birth on these boards because it was warm there anyway. Centuries-old houses still have those tables.

A resident of the village of Velymche shows off her wedding dress. Photo by Lyudmila Gerasimyuk

The researcher adds: the more straightforward you go to people, the faster they open up and share memories and thoughts. She names three life hacks that have long since become classics: eat, pray, and love.

Eating means not shying away from everyday life, not being afraid to go to people. They want to treat you to tea — if you can, don't refuse. If you want to give something to taste, try it. The best way to get along is over food. Sometimes Livitska uses conversations about food:

"If people don't want to talk about difficult memories, I ask: 'Tell me what your grandmother used to cook for you when you were very young. What did you eat then?'. These are memories that come very easily. They are nice. And after them, other stories come crashing down."

The old door in the Trinity Church in the village of Trostyanets. Photo by Lyudmila Gerasimyuk

Pray is to accept the world of people. They are taking you to the church — go, look, listen. Even if you don't intend to write about it or you won't be surprised by anything there. This is their world, and it is important to immerse yourself in it. And this is not only about the church.

To love is to love — the work you do and the people.

"Our land is unique, and people are all-powerful. We have something to fight for"

Volyn children. Photo by Lyudmila Gerasimyuk

Blue windows, blue doors. A sea of potato food. Traces of former farms between villages. Cross-figures, richly dressed in handkerchiefs, aprons, and ribbons, are very colorful — bright colors against the background of simple Polissia life. The huts are hung with towels and icons. That's all — Volyn.

The most important thing here is the people; they are exactly what Ukraine holds on to.

"At first glance, these are silent people who are allegedly hard to budge, who do not wear embroidered clothes on display but have them. They are very strong; they believe in the forces of nature until now, and, as needed, they will protect Ukraine by becoming a wall. That is why we are now burying a lot of heroes," says Livitska.

A teenager from the village of Shkurat. Photo by Lyudmila Gerasimyuk

"When the Russians blew up the Kakhovska hydroelectric power plant, I took it upon myself to read Dovzhenko's "Poem about the Sea." He wrote about people and villages that were supposed to disappear under the water of the Soviet Sea. I read and thought: people are the same in all villages, and some unchanging images are repeated. You will not erase them," Livitska shares.

Headmaster of the Khotsun school, Anatoliy Gerel. Photo by Lyudmila Gerasimyuk

For example, the researchers got to know the school director in Khotsun, a village in the Lyubeshiv region. The school is on the verge of closing. The village is near Belarus and is quite remote. The school's director, Anatoliy Gerel, an older man, reads Vsesvit magazine, listens to Pink Floyd, follows Twitter, and doesn't like journalists because everything always gets twisted. He protects the village school.

Ostap Susval, Hero's father. Photo by Lyudmila Gerasimyuk

Ostap Susval lives in Susval, a 'difficult and capricious old man.' Ostap is the hero's father. He lost his son, after whom the village was named.

Volodymyr Panasyuk, bell ringer from Buzaki, reads a newspaper. Photo by Lyudmila Gerasimyuk

90-year-old bell ringer Volodymyr Panasyuk is also from Buzaki. He is both a ringer and a butcher. He shares the secrets of how to stuff karukh with ribs. Karukh is a pig's stomach or urinary bladder, cleaned and stuffed with seasoned meat, then dried — it is a Volyn specialty.

Anastasia Finikovska from Wola Uhruska became a Tik-Tok star. Photo by Lyudmila Gerasimyuk

Anastasia Finikovska, from Wola Uhruska near Poland, is 88 years old. She became famous on TikTok by reading poems.

Hryhoriy Zarubych from Smidyn and his homemade hockey sticks. Photo by Lyudmila Gerasimyuk

Hryhoriy Zarubych from Smidyn in the Starovyzhiv region — at age 67, he goes out every winter to play hockey. He keeps the sticks he made himself under the house — for the whole team. They play hockey all over the street. And for the soul, he writes humorous stories about his neighbors.

Kostyantyn Bobrych from the village of Toboly. Photo by Lyudmila Gerasimyuk

Former village head Kostyantyn Borbych went to fight as a volunteer when the war just started. He returned and has been working at the military commissariat ever since. He researches the history of villages and knows all the nooks and crannies.

"By some terrible irony of fate, Kostyantyn Bobrych once brought back from oblivion a large World War I cemetery where, among others, the ancestors of those with whom he fought in 2015 and is still fighting are buried. Russian occupiers are killing Ukrainians, and Ukrainians are looking at the graves of their great-grandfathers," says Livytska, a local researcher.

Nadiya Derkach folds her skirt in the village of Buzaky. Photo by Lyudmila Gerasimyuk

This is Nadiya Derkach from Buzaky in Kamin-Kashir district. She keeps 'deadly clothes' in the chest. According to tradition, women 'go to the next world' in wedding clothes, so many unique outfits have disappeared. Derkach would like to pass on her wedding embroidered shirt to her grandchildren to keep, but she does not dare to break the custom yet.

Derkach prepared not only for death but also for war. She put dried crackers in a pot with flowers in case war comes to the house. And the war came to the house differently — it took away her son.

Bread for the war — crackers, dried by Nadiya Derkach. Photo by Lyudmila Gerasimyuk

Despite all the difficulties, age, and troubles, these people, like their villages, do not exist but live. According to the researcher, the secret of these people is their philosophical attitude to life. In their world, they talk about complicated things easily, including death.

"I don't like whining about the villages surviving. Everything has its own time — something remains, something leaves — that's normal. It is important to record this process as evidence, evidence of this passing," says Livitska.

Even more useful solutions!

Zaneslo v selo is a bridge between the past and the future

Viewing family photos in the village of Sviichiv. Photo by Lyudmila Gerasimyuk

The Zaneslo v selo project was temporarily put on hold when a full-scale war broke out.

According to Livitska, there was shock and thoughts: Who will need it now? Who will read about the villages of Volyn when everyone reads news from the war and nothing else?

"Some time has passed — we carefully submitted the first story from Smidyn, the materials collected before February 24," the journalist continues, "and frankly told the readers: we understand that it may seem out of time, but we want to prove the opposite. This war shows us that we have something to fight for. We have something to defend. This is the world, and we will talk about what we need to protect and record. However, every story told during the war is about the war. You cannot avoid these reflections in the texts. They are there. Sometimes literally, somewhere between the lines."

The project will start a column to which the researchers plan to devote the summer and autumn. It is called #Land of Eve. This story is not just about the fate of one family. It is about memory and the power of the native land.

The family of Eva Lazar, a reader of the Zaneslo v selo project, has been living in Britain since 1948, but she used to live in Volyn. Her father, Józef Shinyavskyi, left Volyn with his family before World War II. Józef spent his childhood there and constantly talked about Ukraine. Together with his daughter, he began to explore this region. Her father died, and Eva went to Ukraine without him, but the COVID-19 pandemic began, and then the war. Now Eva volunteers and helps Ukraine. Olena Livitska and Lyudmila Gerasimchuk decided to help her. They will become her eyes. Through them, Eva will see her father's Ukraine.

Zaneslo v selo project: rural landscape, Volyn. Photo by Lyudmila Gerasimyuk

"We want to let her feel, see and understand how here, what has changed, and most importantly: why it happened like that, and not otherwise," explains Livytska, "We now know how strong the power of the earth can be in different senses. Therefore, this project may be more necessary not even for Eva but for those here, at home, who need to learn to appreciate what can be lost. The present shows us that tomorrow may not be possible, but there is no such way to erase everything. Something and someone must remain. The memory should be passed on to them."