"Fragments of consciousness. Explosion. Ringing, pain, leg, fall, blood. 'My leg,' I shout to the world, 'my leg.' It's close under my armpit, torn away. That's it. Shouting is pointless…

Yes, golden hour. I remember the rules of the golden hour—the first hour after an injury, when survival hangs in the balance. Back then, I'd joke with the instructor, saying the golden hour was that time just before dawn when shadow and light reach perfect balance, like artists see it. What does all that knowledge mean now? I need to focus—get a tourniquet…

There's the crater, just five meters away. Small, it didn't even pierce the asphalt. The ground is covered in white from burnt gunpowder and ash. What happened? Just 20 minutes ago, the orcs broke through defenses at the ski base and hit our rear in Bobrovytsa…"

Excerpt from the monoplay "Explosion"

"Sania, Sania, here's a tourniquet—help me!" With bloody hands, I fumble for the tourniquet in my breast pocket. It sticks to my fingers, pulling me into a soft, warm "nothingness," like a cozy blanket. It's quiet, warm, as if I'm back in a mother's womb. No sounds, no war, no explosions or tanks—just "nothing"…

Then suddenly, someone yanks away the comforting blanket of "nothing." "Yura, Yura, don't sleep! Yura, can you hear me?" And yes, I hear them. I respond just to slip back into the sweet "nothing," where I'm wrapped in my grandmother's wool, an unsung lullaby, and a soft duvet. Who are they? How do they know my name? Oh, the dog tag. It has everything on it—even my blood type…

A jolt! The endless, bright Crimean sky fades, replaced by blood-smeared masks, a dull hum, and shoving. We're moving. I wonder if I they will put me in the open trunk, like when they'd transport the wounded and dead from Novoselivka, to keep the upholstery clean. Are my legs bumping over potholes too? Or just one of them? Ah, yes—there it is, the other one, lying on my chest…

I hear my mother's voice, whispering. "Son, are you asleep?" But a rough, terrified voice interrupts, breaking through the sweet "nothing." "Yura, Yura, don't sleep! Talk to me." I see a dirty, unshaven face. Just leave me alone. Take me back to the cinema, back to the "nothing."

Excerpt from the monoplay "Explosion"

"O+," I hear a voice say. Something sharp pierces me. Probably medication, painkillers. Why? I'm fine.

"Yura, can you hear me?" A female voice now—gentle, but firm. Probably a nurse—I can tell.

"Good job, Yura, everything will be alright." I know, sister, don't worry. The doctors will save me. They're angels. You're all angels…

"How are you, Yura?" I try to nod. No, no—tell them—I'm fine. Another prick. We're moving somewhere, people are talking. "Nothing" and "something." Light and dark. Where am I? Here or there?

Voices filter in. The nurse, whispering to someone nearby, says, "Look, he's poking—what's he saying? Another fragment in the other leg? Can you believe it? He says it's dead tissue now, that it won't heal, and he's asking them to just remove it."

Then the doctor snaps, "I know what I'm doing. The amputation is already high. We need to preserve muscle for him to use a prosthetic."

I scan the room: empty beds, tiled walls. Is this the operating room? Intensive care? Someone leans over me, their face hidden behind a medical mask. But their gray-blue eyes are gentle—angelic.

"Oh look, he's awake. How are you, Yurii Ivanych?"

"I'm fine."

"Nothing hurts? Do you need any more anesthetic?"

"Tequila would be better." Their eyes crinkle with smiling lines.

"He's got a sense of humor." Another pair of brown eyes smiles too. "I'll call the doctor; he'll want to know you're awake."

I smile back. Their eyes—so different, kind, worn, yet bright. I'm fine. Why do I need a doctor? I'm alive; what else matters? Maybe he'll tell me what happened to the others…

What is the problem?

These are excerpts from Yurii Vetkin's autobiographical monoplay "Explosion." Vetkin, a veteran, first fought in 2016 near Sloviansk before resigning from service. In 2022, he returned to duty and was assigned to serve in Zhytomyr. However, he faced the enemy in his hometown, Chernihiv, where he was injured by a mortar attack during a mission, resulting in the loss of his leg. Today, he is a veteran of the ongoing war.

He is one among many. As of July 2024, about 1.3 million veterans live in Ukraine, according to Deputy Minister of Veterans Affairs Ruslan Prykhodko. This number continues to grow, and the Ministry of Veterans Affairs estimates that, by the war's end, there could be around 5-6 million veterans in Ukraine.

"That's one in every six Ukrainians," noted Maxym Kushnir, then Deputy Minister of Veterans Affairs.

For Ukraine, developing a comprehensive policy on veterans' rehabilitation and reintegration is critical, and the work must start now. A key aspect of this process is listening to veterans and valuing their stories.

"As a matter of survival, veterans need to tell their stories, or others will tell them for them, and inaccurately. This would set our society back. By sharing their stories, veterans can also challenge our adversary in the global narrative market," says Maksym Kurochkin, co-founder of the Veterans Theater project.

What is the solution?

In April 2024, TRO Media, in collaboration with Playwrights Theater, announced the launch of the Veterans Theater project. This initiative is designed for individuals who have experienced traumatic events, suffered injuries, contusions, or loss of limbs.

"Initially, we explored international practices, reviewed specialized literature, and studied articles, confirming that theater is widely used worldwide as a recovery tool, helping individuals return to a full life," explained Maksym Kurochkin, one of the project's co-founders.

Maxym Kurochkin. Photo: Facebook/"Veterans Theater"

The primary goal of the Ukrainian Veterans' Theater is to teach veterans the art of drama. Unlike typical programs, which focus on acting, this project aims to help veterans share their personal stories through theatrical performances. "This is our know-how," says Kurochkin.

How does it work?

The first step was to assemble a group of veterans. Around 40 individuals applied for the Veterans Theater inaugural course. After conducting interviews with each applicant, 17 participants were selected.

"We understood that this initial course would be exploratory. We lacked the resources to expand the project further at this stage. So we focused on veterans who could either be in Kyiv or could come to Kyiv for part-time training," explains Kurochkin.

Training began on June 18, mainly consisting of lectures and hands-on workshops. Veterans were taught by directors, playwrights, actors, and producers — "professionals from the creative field specializing in socially significant narratives." Kurochkin recalls warmly that everyone he invited to lecture was eager to support the veterans.

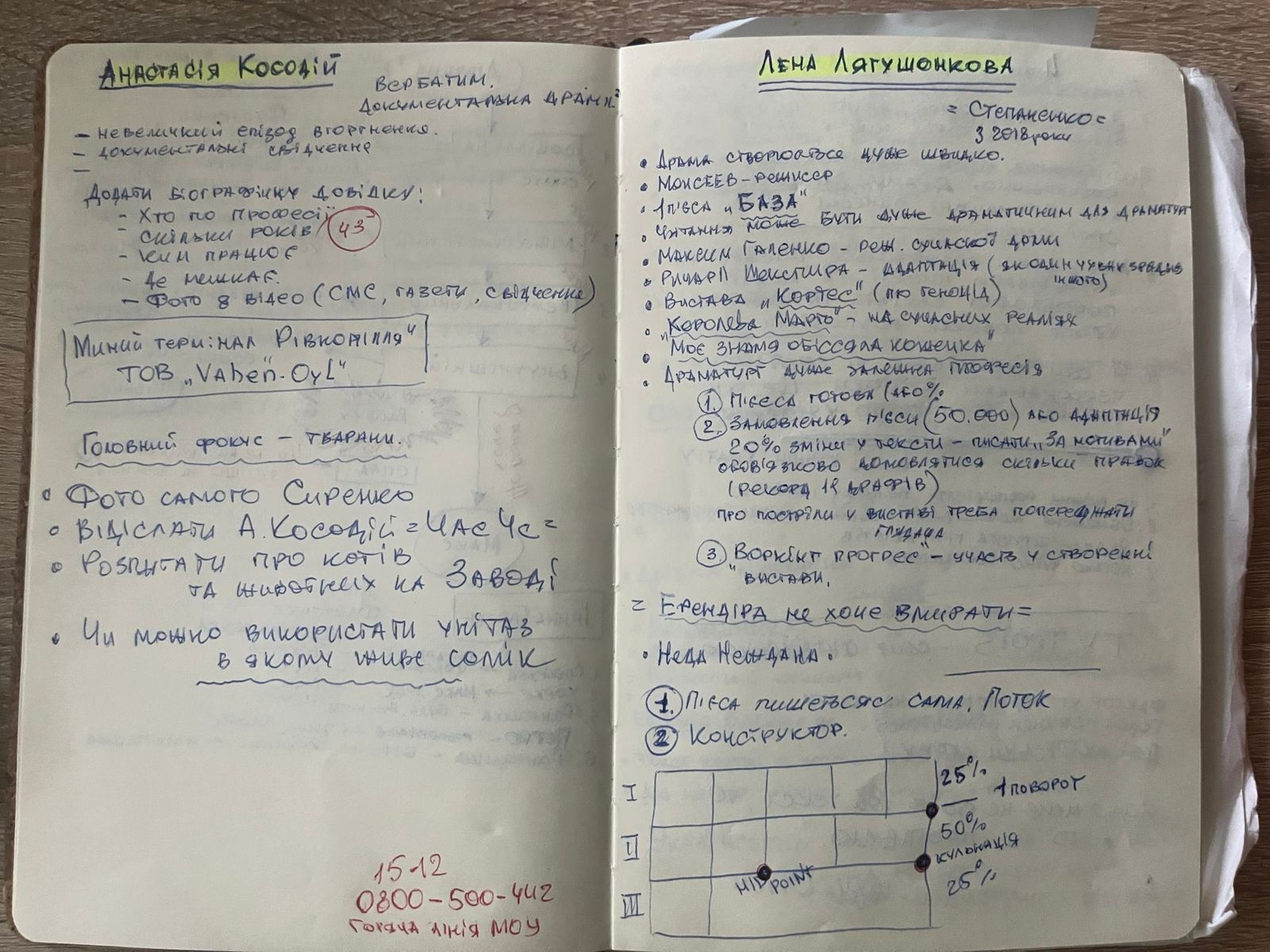

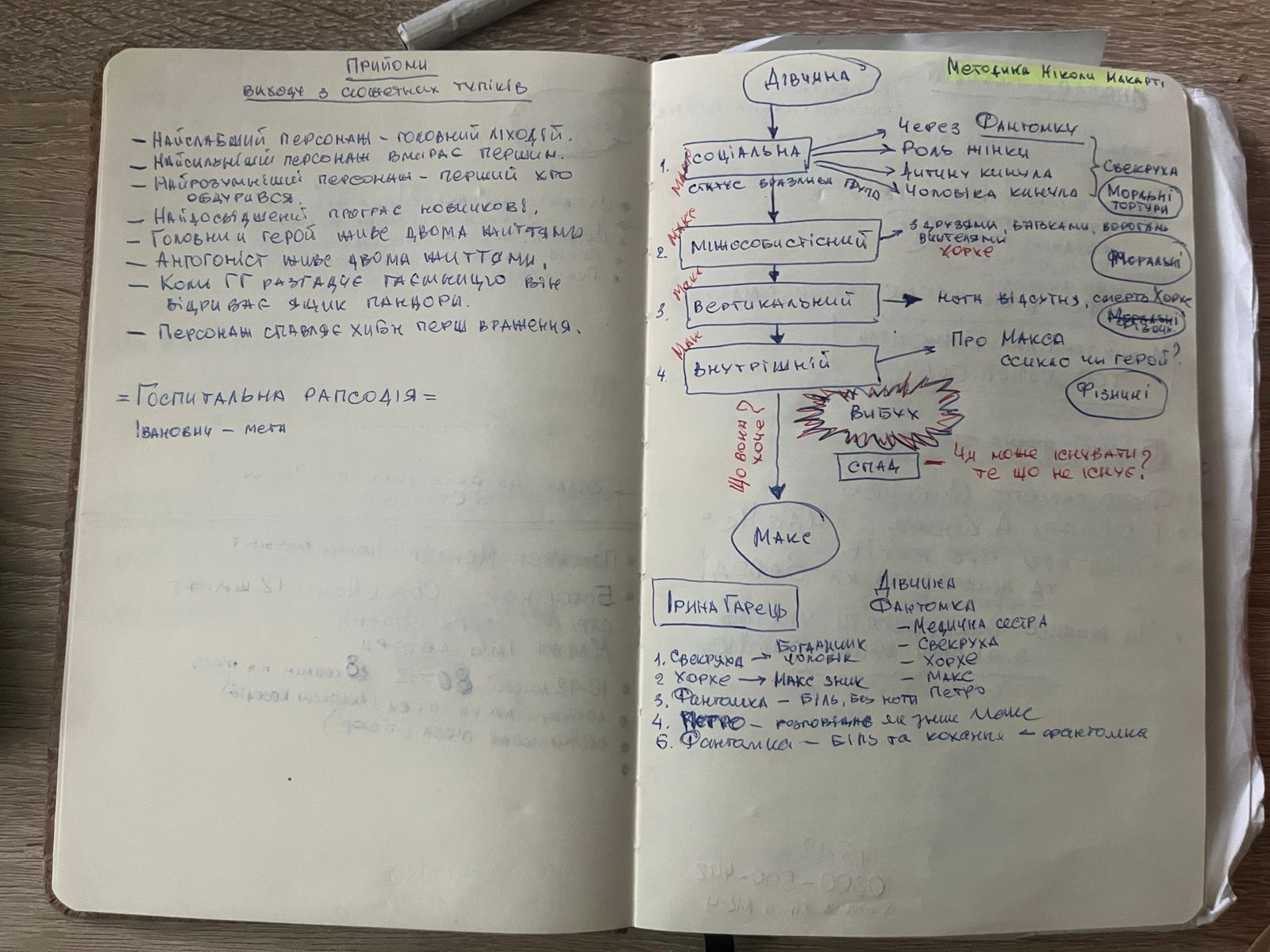

Yurii Vetkin, the author of "Explosion," speaks with enthusiasm about the lectures. "I attended every lecture, trying to absorb everything. I took extensive notes and made a detailed synopsis. We studied the hero's journey, elements of acting, and various theater forms. It was all a revelation for me," says the veteran.

Notes by Yurii Vetkin. Photo from the hero's personal archive

Vetkin recalls that from the first week, they began working on their own plays, encouraged by their curator, Maksym Kurochkin. He quotes Kurochkin, who believed that everyone, especially military personnel, has at least one story worth telling that could be crafted into a play. The team of experts was there to assist right from the start.

During the course, he managed to write three plays, one of which is titled "Explosion." Originally, it was a Facebook post, then evolved into a chapter of his future book. When director Olena Hapeyeva read it, she encouraged him to adapt it into a play.

"'Explosion' is about how I lost my leg and the emotions that come to a person fighting for their life—or rather, when others are fighting to save you, because, in moments like that, not much is under your own control," the veteran explains.

Yurii Vetkin at the Festival of First Plays

While developing their plays, veterans frequently consulted lecturers and mentors for feedback. The organizers emphasized guiding veterans to find "more effective expressions, more precise language, and more complex structures" rather than writing for them.

Kurochkin shares the story of veteran Hennadii Udovenko, who had little prior writing experience. Udovenko made 16 versions of his first play, each time making substantial improvements—not fundamentally altering the text, but enhancing it significantly. His second play, however, reached a polished state after just two revisions. "The progress is obvious," Kurochkin notes.

Beyond playwriting skills, these classes serve a therapeutic and restorative purpose for the veterans. Vetkin agrees, which is why he's now working to establish a similar initiative in his hometown of Chernivtsi.

"For us, the most meaningful result was a simple post by Hennadii Udovenko, a veteran and graduate of our program. He wrote in a private chat, 'For the first time, I like myself.' Hearing such words from someone who has endured a challenging life and faced many hardships is a tremendous honor for us. That's when we knew this truly works," says the theater's co-founder.

Another core principle of the Veterans Theater is authenticity. No one tells veterans what they should or shouldn't write about, and there's a commitment not to censor or soften the subjects veterans wish to address. The theater believes it's essential to give veterans the space to share their honest stories, with guidance on structuring them for the stage.

"Most veterans wrote about the war, which is natural. They need to process their own experiences and traumas. The plays are, of course, largely about the war, but this was never a requirement," says Kurochkin.

The theater also respects veterans by treating them as individuals with complex identities and meaningful contributions. This is not a typical therapy where veterans are seen as patients, but rather as thoughtful individuals with insights valuable to society. "This principle has always guided the 'Veterans Theater,'" Kurochkin explains.

Veterans Theater. Photo: Facebook/"Veterans Theater"

When the plays were ready, veterans began selecting directors to bring their works to life at the "Festival of First Plays." Directors, in fact, competed to direct these stories, each initially choosing a few scripts that interested them. The authors then picked the director they felt most aligned with their vision.

A key rule in working with directors was that no changes could be made to the script—no words omitted or altered—without the author's approval. The organizers also emphasized that the director should capture both the verbal and non-verbal elements to remain true to the playwright's original intention. Meanwhile, veterans received guidance on how to effectively collaborate with directors.

At the Festival of First Plays, veterans showcased the pieces they developed throughout the program. Over three days, 15 plays were performed. Additionally, Yurii Vetkin and Oksana Tsiba's play, "Turn to Irpin," was presented in the "Paper Theater" format, while director and screenwriter Marysia Nikityuk introduced the first draft of her new film about military sappers, "Noi."

The Festival of First Plays.

"For us, there is no such thing as a bad result in this project; everything is part of the learning process. In that sense, the Festival of First Plays is not a conclusion but another phase of training," says Kurochkin.

The project team is now focused on refining the training courses and their concluding stages. After the first festival, they realized that adjustments were needed: reducing the density of performances, allotting more time for discussion, and preparing facilitators to guide these discussions. At the same time, the organizers believe this format should be repeated once or twice more.

"This structure will largely stay the same. We know we'll have two more similar sessions, after which we'll need to change the format to keep it fresh and impactful. But for now, we need to continue. We truly believe that drama is one of the most universal ways to help individuals heal," Kurochkin explains.