Pavlivka of the Bilopillia community is a village stretched for ten kilometers along the river of the same name, and at the edge, it comes close to the border with Russia. Like almost all villages on this border, it suffered a lot from shelling. Volfyne, Shpyl, and Katerynivka were the most affected in the community — those villages actually no longer exist.

We go around the village accompanied by the village head, Svitlana Fedorchenko. According to her, before the full-scale invasion, more than 1,500 people lived here; now, there are about 260. They are mostly seniors, although there are also young people and children. Despite the constant risk of being killed by shelling, those who have remained do not want to leave. They often do not know where they can move to and what to do there. They say ₴2,220, less than $100 of aid, is insufficient to start a new life. In addition, other challenges will arise in a new place: employment problems and adapting to a new community.

Sad conversations

The streets in Pavlivka are empty. Fedorchenko shows destroyed houses and tells about the dead. Three people died in the community, two in Pavlivka and one in Volfyne.

We pass by a destroyed house. Fedorchenko says here, an older lady died due to shelling.

The head of the village tells about another person who died — a man was just working in his garden when a missile struck near his house. An older man in Volfyno died from a shrapnel that flew into his house.

Everyday life in the border community

The village has two shops: one is open all the time, the other is open twice a week. There is a post office, which also operates twice a week, and a farm. However, due to mining, many lands in the community are not cultivated.

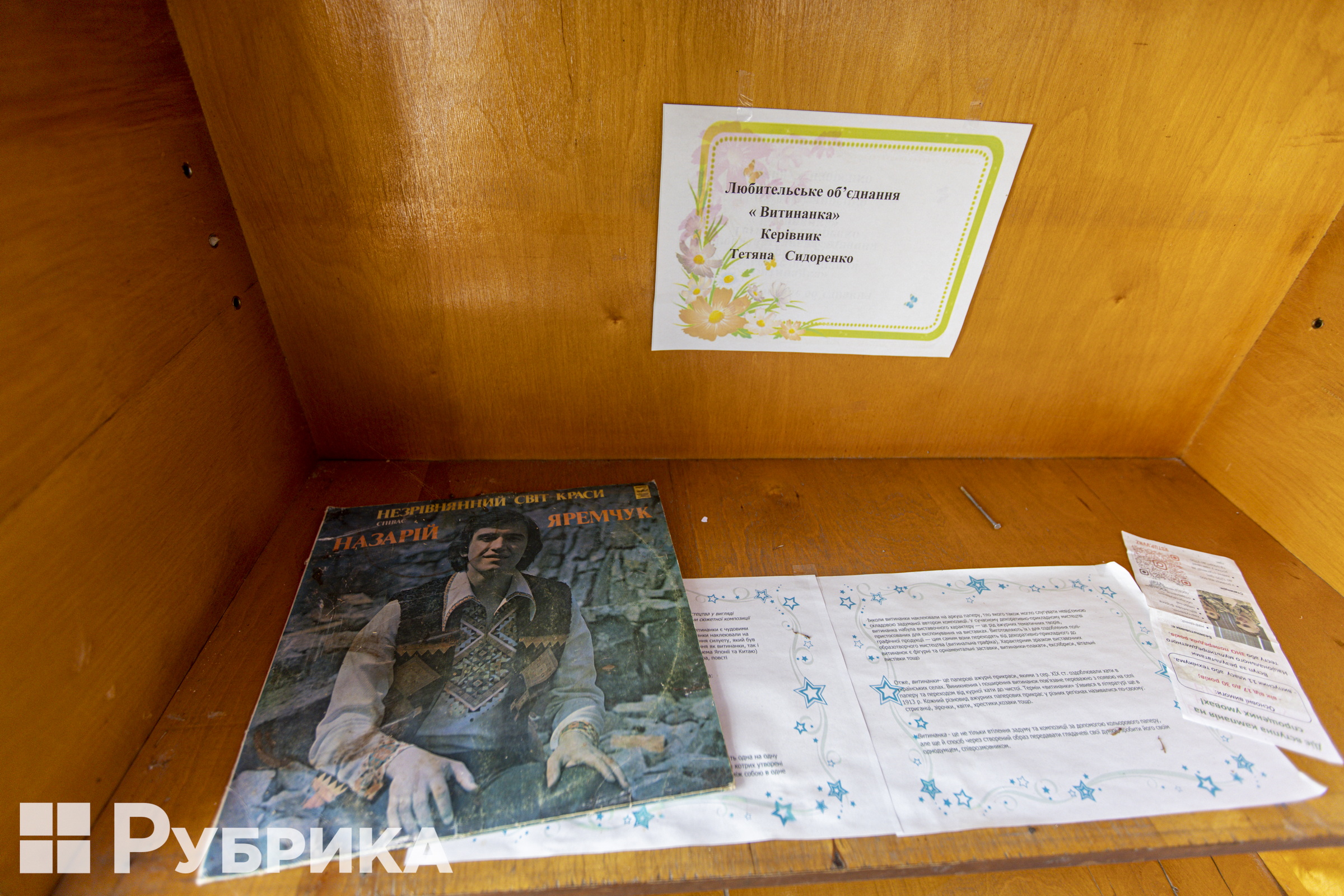

We approach the house of culture.

Fedorchenko asks not to take pictures of the untrimmed grass. The village elder is ashamed — she says that everything was neat before.

In November of 2022, the center of culture had just finished providing humanitarian aid when targeted shelling began. Fortunately, almost all the villagers had already left. Only the headman, the artistic director, and four other workers remained. If the shelling had been a little earlier, it would hardly have passed without casualties.

Now, when humanitarian aid is brought, Fedorchenko asks the farmers for a car, and aid is delivered point by point in the village.

There is often no electricity here due to shelling, but Fedorchenko assures that they are restoring the supply quite quickly. However, the village now faces another, more complex problem — preparation for winter. Before, it was possible to collect firewood, but now it is impossible due to shelling.

"If not for the war"

On Our way, we meet Mykola.

He has lived in the village all his life and does not want to leave anywhere. "There's nowhere to go," he adds. Mykola and his wife have a farm — they keep a cow and sell milk. He says he has been used to constant shelling for a long time. The man smiles and explains that he is happy to have his house intact.

Another local, Serhii, is sitting by the fence of his house.

Serhii is 51 years old and has also lived in Pavlivka since birth.

"They shoot here often, sometimes every day, sometimes every other day," Serhii says. The villagers have long been distinguishing between the various war sounds. He says there was not much work in the village even before the war and even more so now. He does not want to leave and explains that you can go when you have money. "Well, no one needs you anywhere," the 51-year-old smiles sadly. Serhii has a disability, will not be able to work, and does not want to panhandle. At home, he has a farm, chickens, a piglet, a cat and a dog. "If it weren't for the war…" the man sighs.

We meet Viktor near another damaged house.

The 47-year-old Viktor is engaged in farming. He shows his house's destroyed roof, which is now covered with a film. Viktor says that now the problem is to buy slate. He was injured during the strike but now can walk, albeit with difficulty.

"I walk slowly, and that's all," says Viktor. 'When I go to bed in the evening, my legs burn to the point that I can't fall asleep. My kidneys hurt, and so does my heart. The missile struck ten meters away, and the shock wave was strong."

Life in the village today is difficult. Yet, walking along it, we notice the details of the pre-war period — goats graze near the road, flowers bloom, sometimes cars drive, or someone rides a bicycle. At this time, it is quiet here — no explosions are heard, and everything is as it used to be in peacetime. However, a few hours after our departure, powerful shelling is heard near the village, which can be heard several kilometers away.