What is the problem?

Russia's war continues to destroy Ukraine's historic architectural heritage. The Drama Theater in Mariupol was one of the first to be lost following full-scale invasion, and afterward, several other precious cultural monuments were demolished – like the 120-year-old building on Zhylianska Street in Kyiv, or the early modernist complex in Lviv, built in the 1930s.

However, it's possible to save these buildings with the help of the most advanced 3D modeling techniques.

What is the solution?

Architecture is digitized all over the world

In an age of technology and digitization, it may seem strange that some works of art have yet to be brought into the digital world.

The idea of "digital heritage" was created in 2003, with the UNESCO Charter on the Preservation of Digital Heritage. One of the key objectives of archiving of cultural heritage digitally is to make it accessible to current and future generations.

An example of digital heritage can be an electronic copy of paper documents, monuments, paintings, a 3D model of a statue or even a building, or an original that exists only in digital form. In the context of architecture, it means constructing 3D models of buildings.

Long before the Russo-Ukrainian war, 3D scanning was applied in anticipation of the risks posed by disasters like fire, flood, or damage to valuable buildings. In 2015, before the notorious blaze at Notre Dame Cathedral in France, architects created a 3D model – thus, when it came time for the rebuild, they could accurately replicate the intricate elements lost to the fire.

French firm Iconem has been making 3D models of cultural artifacts that are in danger due to military conflicts for over a decade. Yves Ubelman, founder of Iconem, had been operating in countries affected by war such as Syria, Afghanistan, Lebanon, Armenia, and has worked on digitizing many historic sites before coming to Ukraine.

How does it work?

Creating a 3D model requires great precision. Technicians place markers that resemble QR codes around a building with double-sided tape. A laser scanner then measures the distance from one marker to the next and records their spatial coordinates.

The scanner creates a precise 3D model. First, it does a quick lower-quality scan, and then specialists mark certain areas to scan specific elements. Photos are taken using cameras on tripods with the right amount of light to make the images as clear as possible so that the model accurately represents a digital double of the building.

Ukrainians are learning from the best – 39 buildings in the west of the country have already been digitized

When Ubelman came to Ukraine last year, it was not to start a new venture for his company — but to pass his knowledge on to Ukrainian architects, who surprised him with their experience and skill.

The Skeiron project started up in Lviv back in 2016, and it's all about digitizing museums, showcasing architecture, and creating virtual tours. Skeiron's "Feel Ukraine by Touch" charity project is well known; they had architects make 3D models of seven architectural structures in Lviv so that visually-impaired people could imagine what the buildings of their city look like. The team also developed the "Pocket City" mobile app that lets you explore 3D models of famous architecture, plus the "Museum in 3D".

Skeiron team founders Andrii Hryvniuk, Yurii Prepodobnyi, and Volodymyr Zayats in 2020. Photo taken by Kateryna Moskalyuk and sourced from the Local History Museum.

From the start of the invasion in March 2022, Skeiron began taking a look at the architecture in their home city of Lviv. The city's historic center is designated as a UNESCO World Heritage site, and ensuring its preservation is a priority.

The Save Ukrainian Heritage project team has already used a special laser to scan 39 cultural sites in western Ukraine, as Iconem does, and over 200 objects through photogrammetry technology – which uses two-dimensional images to build a 3D model.

Yuriy Prepodobny, one of the members of the Skeiron team, in an interview with Local History in June of this year, said that one of the most significant projects they are currently working on is Chernivtsi University:

"If we take around a thousand photos and set up 20-40 scanning points while scanning a typical wooden church, [then] Chernivtsi University will have over 20,000 photos and over three thousand scanning points. These files are really huge – 2.5 terabytes. We've been scanning this monument for a month and have been working on it [Chernivtsi University – ed.] since December. At the same time, we have been scanning other things, like St. Sophia Cathedral. We were lucky because the Austrian firm RIEGL, which manufactures scanners, gave us the necessary equipment, and we managed to get it done in just one week," said Yuriy.

Architects and geodesists began to create 3D models of buildings in Mariupol

Skeiron also has another project strictly related to Mariupol — Save Mariupol Heritage.

"By the end of September 2022, Oleksiy Heneralov contacted us and sent us pictures of the Mariupol Drama Theatre, which had been decimated during the city's bombing. After that, we started a crowdfunding campaign to get a hold of pictures and videos to acquire as much information as possible to build a 3D model of the theater, the area close by, and other noteworthy buildings. With the aid of photogrammetry technology, we acquired thousands of photos and constructed a 3D model of Mariupol," the project's website says.

The Skeiron team created the 3D model of the Drama Theater in Mariupol. Source: Skeiron

You can try out a 3D tour of the drama theater on the project website. Additionally, the team is looking for pictures that can be used to make 3D models of other landmarks in Mariupol.

Skeiron isn't the only one on the scene regarding 3D modeling of buildings. Digitization of cultural heritage is done by the Pixelated Realities team from Odesa, which also works on 3D modeling, the Kyiv company AERO 3D, which creates 3D models and sells them through NFT technology, and My Future Heritage from Lviv, which scanned most of Pinzel's sculptures in the city. All of them aim to preserve cultural heritage in digital format.

3D models of already destroyed buildings are being created in Ukraine. Why?

Kyiv architect Serhiy Revenko and his partner web designer Mykita Solopov have teamed up to make 3D models of Ukrainian historical buildings destroyed during the Russian invasion, and launched the ScanUA project to highlight Ukrainian heritage amid the devastation of war.

Among the scanned objects are the destroyed buildings of the library and cinema in Chernihiv, the Church of the Ascension in Lukashivka in Chernihiv Oblast, the school and fire station in Kharkiv, the destroyed bridge in Irpin and the psychological rehabilitation center in Borodianka. The architect also scanned a residential building destroyed by a kamikaze drone in Kyiv on Zhylianska Street.

View this post on Instagram

These technologies enable us to not only keep cultural heritage safe, but also come in handy in forensic examinations. In an interview with Suspilne media, Ella Simakova-Efremian, deputy director of the Bokarius Forensic Science Institute at Ukraine's National Scientific Center, stated that the laser scanning method is utilized to evaluate and document harm to buildings and infrastructure. She added that this method enables experts to detect even the tiniest damage and cracks, significantly shortening the time span of their work.

3D models can be a significant part of rebuilding. This is how Notre Dame was reconstructed after the fire

Directors and architects of the French company Art Graphique et Patrimoine (AGP), made detailed digital scans of most of the Notre Dame Cathedral in 2015, recording the architectural monument before the fire broke out. In April of this year, they told Fast Company how it was created, and how both old and new scans of the cathedral played an essential role in the cathedral's reconstruction, which is due to reopen in 2024.

It took over a year to make the initial digital model consisting of more than 12 thousand pieces, 30 thousand square meters of stone wall, and nearly 4 thousand square meters of lead roof with 186 cathedral vaults.

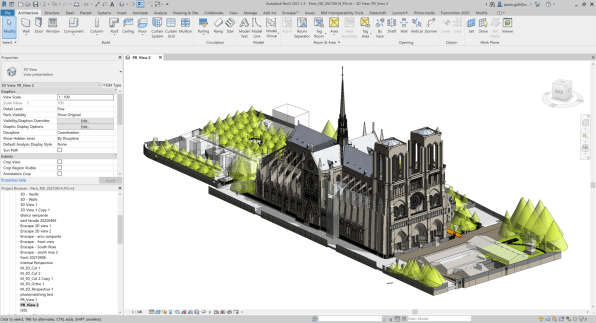

A 3D model of the cathedral, provided by Fast Company, is pictured.

Following the fire, AGP and Autodesk conducted another scan of the building to determine the changes caused by the blaze. Onsite personnel recorded an exacting 3D geometry of the cathedral with the help of lasers and cameras. Using the data acquired from the process, experts were able to craft detailed shapes and objects, down to each individual brick. This helped them understand how the building shifted during the fire, enabling them to predict any potential stability issues and plan the rebuilding procedure. It took about a year to complete the whole process.

The rebuilding of Notre Dame Cathedral. Credit: Financial Times

Today, architects and engineers can utilize the 3D model for anything ranging from modeling varied lighting options for the renovated cathedral to meticulously organizing the positioning of trucks, cranes, and other equipment on the tiny Parisian island where the cathedral is located.

An image of a 3D model of the cathedral provided by Fast Company

Even after the cathedral reopens, the model can still be useful. The company is now talking about using it to regulate certain parts of the complex in the future, possibly with sensors that could identify the site of future fires.

What if not everything can be preserved? 3D models as cultural heritage

A few Ukrainian museums have begun digitizing their collections in response to the threat of full-scale war. An instance of this is the Zhytomyr Regional Museum of Local Lore, which will be preserving its displays digitally by mid-March 2022, with backing from the European Union.

"If we lost any Polissia embroidery or Easter eggs painted in the Zhytomyr region, we would have no chance of finding such replicas in European museums. These items are an essential part of our Ukrainian identity," said Roman Nasonov, the museum's director.

According to Nasonov the work of digitization is very tedious; there is not enough equipment in some places, and to fully digitize the collection, scanners are also needed in addition to photo equipment.

3D scanning technology is open to everyone

You can use digital technology to preserve your house, or scan ruins so you can reconstruct them with precision.

In Kharkiv, Ukraine – one of the places hit hardest by missile strikes – the Bokarius Institute of Forensic Expertise uses 3D scanning to examine buildings damaged from shelling, missile attacks, and air raids.

The institute states that anyone is eligible to obtain such an examination. A virtual model can be used as proof in the event of a lawsuit for damages or, as the articles demonstrate that it takes about two hours to do a 3D scan of a nine-story building that's been destroyed, but building a 3D model out of it requires a whole lot longer.

It is worth noting that the cost of such a service is not insignificant – depending on the size of the house, it can cost up to several thousand hryvnias. Many companies offer building scanning services.

To scan or not is a personal decision of everyone. However, now, in times of war, it can be a kind of insurance or investment in future reconstruction.