Davos on a wing and a prayer: How World Economic Forum went for Ukraine and everyone else

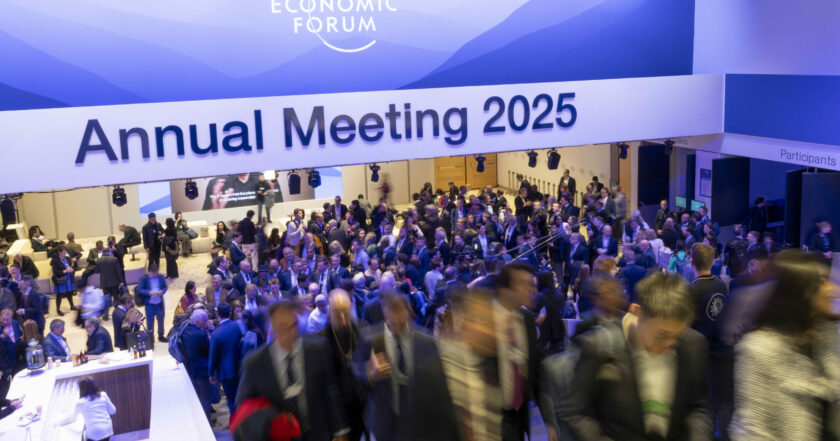

This year's World Economic Forum (WEF) in Davos drew exceptional attention. On one hand, it was the 55th edition — a milestone that calls for something special and different from the previous ones. On the other hand, for the fourth year in a row, the conference in the Swiss Alps took place against the backdrop of the bloodiest war in Europe in decades, a war that continues to claim civilian lives. That alone was reason enough for this year's forum to stand out.

Ukrainians weren't expecting the economic summit to become a peace conference, but they would've welcomed some news of investments in their country. Then again, the WEF isn't an investment fair nor an extension of Ukraine's recovery conferences on a new stage where commitments could magically materialize.

The potential gap between expectations and reality is embedded in the very name of the event. It's a classic logical trap if you will. Despite its grand image, the WEF is first a non-governmental organization and a think tank. Only then is it a high-profile gathering of political and business leaders, investors, experts, journalists, and celebrities from various fields. In other words, it can afford to indulge a little — especially when it comes to research and analytics.

Traditionally prepared by the Forum, this year's Global Risk Report opens with an assessment of "greater instability, polarizing narratives, eroding trust and insecurity." It goes on to stress that today's governance systems "seem ill-equipped for addressing both known and emergent global risks or countering the fragility that those risks generate."

The wording may be in high Elvish, but the message is crystal clear. Unlike national governments, which are primarily concerned with domestic affairs, the WEF focuses on globalization and the challenges that come with it. What's particularly striking is how this contrast stands out against the shift in the US presidential administration. While Trump radiates confidence in the necessity of protectionism and an "America First" approach, the WEF continues to champion the free movement of goods, services, technology, and labor.

The report presents findings from this year's Global Risks Perception Survey, which, in its own words, "brought together the collective intelligence of over 900 global leaders across academia, business, government, international organizations, and civil society," along with "some 100 thematic experts, including the risk specialists." And the conclusions are genuinely fascinating.

For instance, interstate wars are the greatest threat to global stability. 23% of respondents named them the top risk, compared to 14% who cited extreme weather events, 8% who pointed to geo-economic confrontations, and 7% who highlighted disinformation and media manipulation. As dangerous as floods, hurricanes, and the overwhelming spread of AI-generated content on social media may be, war remains an unparalleled catastrophe. What Putin and his cronies are doing in Ukraine eclipses any extreme weather event in terms of devastation.

So, it's reassuring to see this recognition, but it feels oddly short-lived. In the two-year outlook, war slips to third place, and in the ten-year forecast, it disappears from the top ten global risks entirely. One can only hope this is part of some cunning strategy to lull potential aggressors into complacency — because an army of experts surely can't overlook an obvious, ongoing threat. Right?

"Let's make WEF great again"

The COVID-19 pandemic, whose effects lingered for about three years, along with armed conflicts — especially Russia's aggression against Ukraine — have shaken trust in international institutions. Consequently, questions about the relevance of the World Economic Forum have also surfaced. Interest in the forum is still strong, but annually attending Davos has lost its once-unquestioned status as world leaders have started skipping it more often.

Sometimes, it's Joe Biden who doesn't show up; other times, Olaf Scholz ends up representing the entire G7. This year seemed different, partly thanks to the calendar — Trump's inauguration day (or vice versa, depending on Greenwich time) coincided with the forum's opening. Trump's first international speech stirred enough curiosity to keep the forum's buzz alive. Even Pope Francis kept his finger on the pulse, sending a special message to participants about the role of artificial intelligence in bringing nations together and urging governments and corporations to ensure AI doesn't exacerbate inequality or conflict.

By the way, there's another entirely different example of how national and global issues are interconnected. The High Court of England and Wales recently barred Russian TV channels Russia Today, Spas, and Tsargrad from seeking to seize Google's assets or imposing astronomical fines with 30 zeros. It's yet another way to make a global statement — but we digress.

Trump's address spawned a lot of hype but wasn't exactly groundbreaking. Rehashing his speech, especially its Ukraine section, would be pointless. It read like a summary of his campaign promises: the war must end, efforts to achieve a peaceful resolution are ongoing, a meeting with Putin is necessary, and China might be able to help. A relatively new element was that the US would appeal to Saudi Arabia to lower oil prices to undercut the financial backing for Putin's war. Meanwhile, Ukrainian politicians focused on strengthening their position.

Ukraine's Economy Minister, Yulia Svyrydenko, pointed out how foreign businesses' views on Ukraine have shifted — from expecting an economic collapse at the start of the full-scale invasion to now making plans based on more optimistic forecasts. Economic growth alone, however, isn't enough. These businesses are still worried about the security of their investments and are interested in guarantees to protect them. In light of this, Svyrydenko made an interesting proposal to foreign businesses to push their governments to create a new kind of 'security guarantee.' It's a bold yet reasonable move. In simple terms, Ukraine needs investors as much as investors need Ukraine.

So, what do the hard, cold numbers tell us? Ukraine's Minister for Strategic Industries, Herman Smetanin, pointed out that parts of Ukraine's defense capabilities are underused because of a lack of funding. He also said Ukraine needs $20 billion for long-range missiles, drones, and air defense systems. President Zelensky echoed this during a press conference with Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk, noting that arms and military equipment produced for Ukraine's armed forces are split in a 30:40:30 ratio between Ukraine, the US, and the EU. Within a week, this ratio shifted to 40:40:20, but the key takeaway is that back in 2022, the US supplied 90% of new equipment. So, this shift represents real progress, which should reassure potential investors.

Denmark's approach to purchasing ammunition and armored vehicles from Ukrainian manufacturers through partner governments is working well. Ukraine has also partnered with Germany's Rheinmetall AG and the UK's BAE Systems to set up joint military production, showing that such collaborations are both profitable and practical for addressing the needs of the front lines in Ukraine without relying on deliveries from Rzeszów, Poland, or being caught off guard by border blockages.

Ukraine's peaceful reconstruction also needs Western financial support. At a conference in Berlin, Yulia Svyrydenko mentioned Ukraine's need for $12–13 billion to "accelerate growth" and fund reconstruction projects, particularly in power generation. She pointed to the reopening of seaports and financial stability as evidence of how wise such investments are. However, earlier this year, Danylo Hetmantsev, head of the Ukrainian Parliament's finance, tax, and customs committee, noted that net foreign direct investment inflows in 2024 were only $3.64 billion, which is 19% lower than in the same period in 2023.

That said, most Ukrainians believe that foreign investment should be the main engine driving economic growth. Ella Libanova, director of the Institute of Demography and Social Studies at Ukraine's National Academy of Sciences, argues that the government needs to strengthen relationships with Western partners and expatriates. She believes the investment volume will depend on protecting investors' rights and promoting favorable attitudes among Western voters.

Back in 2022, Russia's invasion dominated the discussions at Davos. Russia wasn't present at that year's forum, which led The Wall Street Journal to declare the "end of globalization." The Russian House was turned into a showcase for Russian war crimes. Over time, however, the war has become a routine topic. It hasn't faded from global attention, but the "summit of a thousand leaders" hasn't been able to put much pressure on the aggressor. Then again, could it ever have?

This year, though, we can hold on to some hope. At the end of last year, WEF President Børge Brende raised several questions: Will the war in Ukraine end by spring? How will it happen? Where will the borders be? What security guarantees will European countries give Ukraine to prevent further Russian aggression? While we don't know if he has the answers, he did talk about innovation and creativity in agreements to "make the world a better place" after the forum.

Indeed, the prospects in the Middle East and Sudan are overshadowed by "fear and uncertainty," as the WEF's Global Risks Report puts it. Still, in Ukraine, the war has escalated to a horrific intensity that feels closer to genocide than vague metaphors about unclear futures. At least Ukrainians are convinced that this war is driven by Russia's desire to destroy an independent Ukraine.

Maybe the Davos Forum, with its eternal focus on the future, is already preparing for a confrontation between humans and machines. Perhaps it can't offer much help in this war, given its role in global public and private partnerships, but can't afford to remain in an illusion of safety. One of the road signs in Davos, often packed with foreign cars during the forum, has a simple but pointed message: "Don't follow your GPS."