What's the problem?

Right now, the only reliable source tracking Kyiv's abandoned buildings is an interactive map of the capital's historical heritage created by a local nonprofit, Renovation Map. The organization's research shows that nearly 400 abandoned buildings are in two districts alone — Shevchenkivskyi and Podilskyi. And that's just a rough estimate, says Mariia Panchenko, a cultural expert who's part of Renovation Map.

"In the Shevchenkivskyi area alone, we've found 227 abandoned buildings. It's an overwhelming number," says Mariia Panchenko. "We quickly realized that trying to catalog every neglected structure in all ten districts of Kyiv was too challenging. Instead, we decided to focus on buildings that hold real historical or architectural value."

"Architectural Monuments" sign on Sichovykh Striltsiv Street. Photo: Liza Bykova

Mariia also noticed a troubling pattern: one of the most common reasons these buildings fall into ruin is that they end up in private hands. When a private developer buys land in the city center that includes a historic building, there's a good chance they'll let it deteriorate on purpose, waiting for it to collapse or, in some cases, mysteriously catch fire. Then they throw up their hands and say something like: "Well, what else can we do? We have no choice but to tear it down and build something new — twice as tall."

Mariia says, "And that's if we're lucky." Sometimes, it's three times as tall.

That happened to a 100-year-old wooden estate in Pushcha-Vodytsia near Kyiv. In March 2023, this unique example of intricate wooden architecture went up in flames. It wasn't the first time — at least two arson attempts had been recorded at the site in 2020.

Fire at the estate in Pushcha Voditsa. Photo: Ukraine's State Emergency Service

After the fire, prosecutors took the owner — a businessman and Kyiv regional council candidate, Ruslan Braslavskyi — to court, demanding that he restore the estate. Nothing came of it. Meanwhile, Kyiv city council member Kseniia Semenova summed up the tragedy with a bitter observation: this wooden villa survived the Russian occupation of the Kyiv region in 2022 and two world wars, but it looks like it won't survive "idiotism and our city's construction 'traditions.'"

A different but equally grim fate awaited the Zelenskyi Estate, a historic home at 22 Oleksandra Konyskoho Street. Built in 1890, it was one of the oldest buildings on the street and gained recognition as the residence of a wealthy merchant family in the early 20th century.

Photo: Zelenskyi Estate. Photo: Liza Bykova

Photo: Zelenskyi Estate. Photo: Liza Bykova

Photo: Zelenskyi Estate. Photo: Liza Bykova

Despite its significance, it lacked any protected status for most of its history, leaving it vulnerable. In 2017, a construction company called Servit built an 11-story apartment complex right next to it. A year later, the developers attempted to demolish the estate, managing to tear down one wing before public outcry forced them to stop.

Photo: Zelenskyi Estate. Photo: Liza Bykova

The reprieve didn't last. In 2021, developers renewed their push to level the site despite the discussion with the city leadership to preserve the landmark. Activists fought back, gathering 6,000 signatures on a petition to save it, but by the summer, part of the estate was gone.

Then, in 2024, despite continued protests, the mansion was almost entirely demolished. The man behind the final push was Mykhailo Hrechka, its co-owner, businessman, and Kyiv regional council member.

Activist Dmytro Perov wrote in outrage:

"This wasn't an Iskander missile. It wasn't a Kalibr strike. This wasn't the war. This was Kyiv — 320 kilometers from the front line. The construction company Turgenev Build demolished the Zelenskyi Estate, built in 1890. Hired thugs beat activists who tried to stop them."

Photo: Zelenskyi Estate. Photo: Liza Bykova

Ukraine's Ministry of Culture granted it protected status only a few days after the estate had been destroyed. The ministry had previously declared the demolition illegal, but because the building had never been formally recognized as a landmark, the developers had found a legal loophole. Still, the ministry said the building was in the city's historic area, which should've protected it from demolition.

The developers pledged to restore the site in April 2022. Today, all that remains is a pile of rubble.

Photo: Zelenskyi Estate. Photo: Liza Bykova

Mariia Panchenko points out that cases like these are rarely legal. Developers frequently ignore orders from the Department of Urban Development, violate heritage protections, and bypass UNESCO buffer zone restrictions — which often don't exist in the first place. Kyiv's architectural gems continue to vanish, brick by brick.

What's the solution?

"Our problem isn't just bad developers. In every country, developers and local communities have fundamentally different interests," says architect and urban planner Ivanna Malii, quoting Danish urbanist Mikael Colville-Andersen.

Sichovykh Striltsiv Street. Photo: Liza Bykova

Ivanna believes developers will always play "a bit of an antagonist" in shaping cities. That's just how the system works. But that doesn't mean they should be free to do whatever they want — leasing or buying landmark buildings to leave them to decay or destroy. Cities and governments must hold them accountable.

The key, she says, is protective agreements with strict limits and real consequences. The city should allow only restoration for historical buildings, meaning no changes to their function, façade, or structural elements. And if developers break the rules? Heavy fines, property seizures, and the government's right to take the building back by force.

Photo: Zelenskyi Estate. Photo: Liza Bykova

She explains that, in theory, protective agreements are supposed to be signed whenever a historic building is bought or leased. But in reality, that doesn't always work.

"The problem is that these agreements often aren't signed at all. Sometimes, someone makes a deal, buys a property, and later says, 'Oops, we forgot it's protected. We forgot it's a heritage site,'" says Malii.

In the end, she adds, this violation doesn't benefit developers. Activists can step in, legal battles ensue, and the construction site is frozen for five or maybe even ten years. That happened with the Kvity Ukrainy (Flowers of Ukraine) building: in 2022, it lost its protected status, but after a massive public outcry, it was reinstated in 2023.

Photo: Flowers of Ukraine Building. Photo: Liza Bykova

"In most cases, heritage status means only restoration is allowed — any kind of reconstruction is strictly forbidden," says Ivanna Malii.

Restoration means preserving every element as it is, with no alterations. This should apply to buildings where every detail holds historical value. However, some landmarks only have a valuable façade, while their interiors can be modified. In those cases, reconstruction should be an option.

The problem? In Ukraine, even at the stage of defining these concepts, things often go wrong. Take the House with Snakes on Velyka Zhytomyrska Street, for example.

Restoration of a building on Velyka Zhytomyrska. Photo: Liza Bykova

"Right now, it's being 'restored,' and at first glance, it looks fine. Beautiful work, right? But it's not a real restoration. They're using concrete — and concrete should never be used for restoration. It's too aggressive," Malii explains.

She adds that this ties into a bigger issue: weak oversight. Kyiv's Department of Cultural Heritage is responsible but lacks a systematic approach. Even when it does penalize violations, the fines are minimal.

Then there's another glaring problem — Ukraine doesn't officially recognize 'restorer' as a profession. While Ukrainian universities train painting conservators, there's no university program for restorers specifically for architectural landmarks, so the work is usually done by artists or architects who, despite their skills, often lack specialized knowledge. The entire country has only a handful of true restoration experts.

"I believe change is in the hands of local authorities," Malii says. "If they take heritage protection seriously and set strict rules for developers, we will see results. Just look at Lviv."

In Lviv's historic center, most buildings are privately owned but restored at the owners' expense — a system that proves heritage conservation is possible when the rules are clear and enforced.

Why does it work?

Urbanist Ivanna Malii says Lviv has much stronger regulations for property owners. "That's why good restoration happens there."

For example, in Rynok Square, the oldest part of the city, you won't find a single high-rise residential complex. That's because the city requires a special document for every sale or purchase, strictly outlining what can and cannot be done with a historic building.

Zhytnii Market. Photo: Liza Bykova

Kyiv has a similar case — Zhytnii Market in Podil. After privatizing, it fell into terrible disrepair because its owner did nothing to maintain it. The community decided this wasn't the kind of heritage site that should remain private.

Now, the question of ownership is still being debated: should the city retain it as public property, allowing parts of it to be leased out? Or should it be put up for sale with strict obligations to follow a pre-approved architectural plan already in development?

Zhytnii Market. Photo: Liza Bykova

Could business–community partnerships be the answer?

Yes, says cultural expert Mariia Panchenko. A possible solution is a new public-private partnership bill, which has been introduced in parliament but hasn't yet passed.

"It's not quite privatization, but it's also not just a lease. Imagine a state-owned enterprise partnering with a private investor to bring in funding and drive development. This could work well for historic sites, too," Panchenko explains.

What about buildings without heritage status?

"Right now, our legislation lacks clear and well-defined criteria for granting heritage status," says Panchenko.

This leads to almost identical buildings having entirely different legal protections — one is classified as a heritage site, while the other is not.

"Sometimes, one building gets lucky because a famous person once lived there, so it's designated as a historical landmark. Meanwhile, an identical 150-year-old building next door, with no such claim to fame, doesn't qualify," she explains.

Mikhelson's estate in Kyiv. Photo: Lisa Bykova

Ukraine needs legislative change to protect background architectural landmarks that shape a city's character. One potential solution is a proposal before the Kyiv City Council that would ban the demolition or significant reconstruction of buildings over 100 years old.

At the same time, even when buildings deserve heritage status, the process is slow and inefficient.

"Just because a building meets the criteria doesn't mean it actually gets heritage status. The process requires tons of paperwork, which then has to go through the Department of Cultural Heritage. And let's be honest — it doesn't work very fast," Panchenko adds.

That's why so many valuable historic buildings, which should already be protected, are left vulnerable. They could be demolished at any moment.

Even more helpful solutions!

One of Renovation Map's key missions is helping buildings gain official heritage status — even if it takes a court battle. Thanks to their work, around ten architectural landmarks have already been saved.

"Of course, it's not a huge number, but that's because we focus on quality. When we submit a case for heritage status, we see it through to the end," says Maria Panchenko.

The process isn't easy. It takes gathering piles of documents, submitting them for review, and fixing inevitable bureaucratic hiccups along the way.

"But the most important thing to understand is that we can't do this alone. It takes a community that cares," says the activist.

Bessarabian barracks. Photo: Lisa Bykova

Bessarabian barracks. Photo: Lisa Bykova

That community effort paid off this year for a historic building at 24a Sichovykh Striltsiv Street, where the Ukrainian army first took shape in the 20th century.

It all started with Severyn, a Kyiv local who noticed something alarming: the Bessarabian Barracks, despite their deep historical value, weren't protected in any way.

"I'm a programmer, not a historian, but I know a bit about the past. I also live nearby and walk this street all the time. It was named after this very building. I couldn't just stand by and watch it disappear," he says.

Bessarabian Barracks. Photo courtesy of the activist

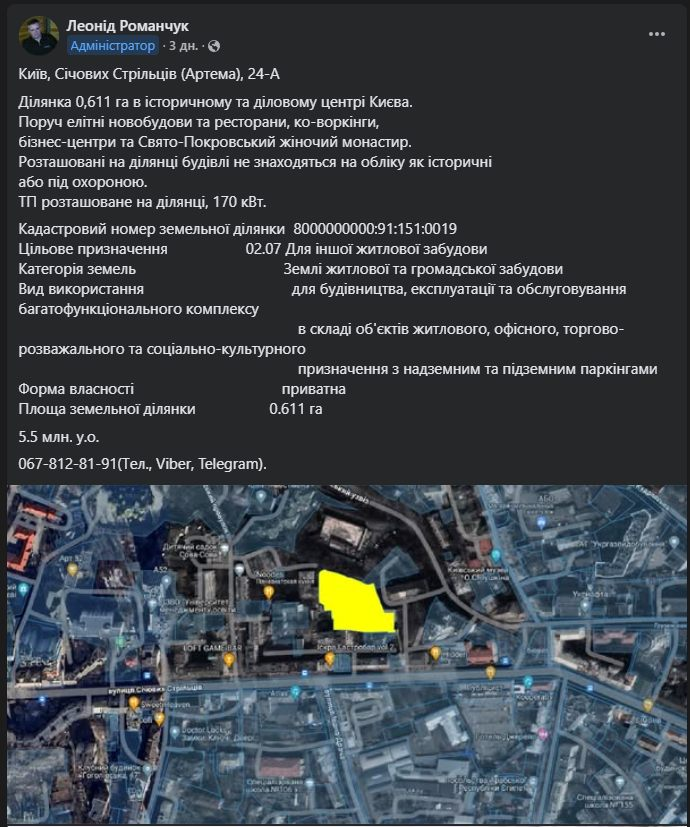

One day, while scrolling OLX, a local online marketplace, Severyn stumbled upon a real estate listing. Someone was selling the barracks — with a bold claim: since the building had no heritage status, it could be torn down or completely rebuilt. Severyn recalls that the price was nearly six million.

"What made me angry was how the seller shamelessly wrote: 'The buildings on this lot are not registered as historical or protected landmarks.' That's when I knew — we had to do something. The risk of demolition was sky-high," says Severyn.

The listing Severyn discovered online. Photo: Screenshot

The first thing Severyn did was bring attention to the issue. He was sure that officials would react, which they usually did when a story gained public traction.

"People started sharing my post, including friends and acquaintances. Some of them probably had large followings. Others began tagging civic organizations in the comments, including Renovation Map."

Next, Severyn launched a petition on the Kyiv City Administration's website and sent an official request to the Department of Cultural Heritage Protection.

"And strangely enough, the petition wasn't published for two weeks," he says.

So the concerned man reached out to Renovation Map, and they promised to monitor the situation and help spread the word.

Bessarabian Barracks. Photo: Lisa Bykova

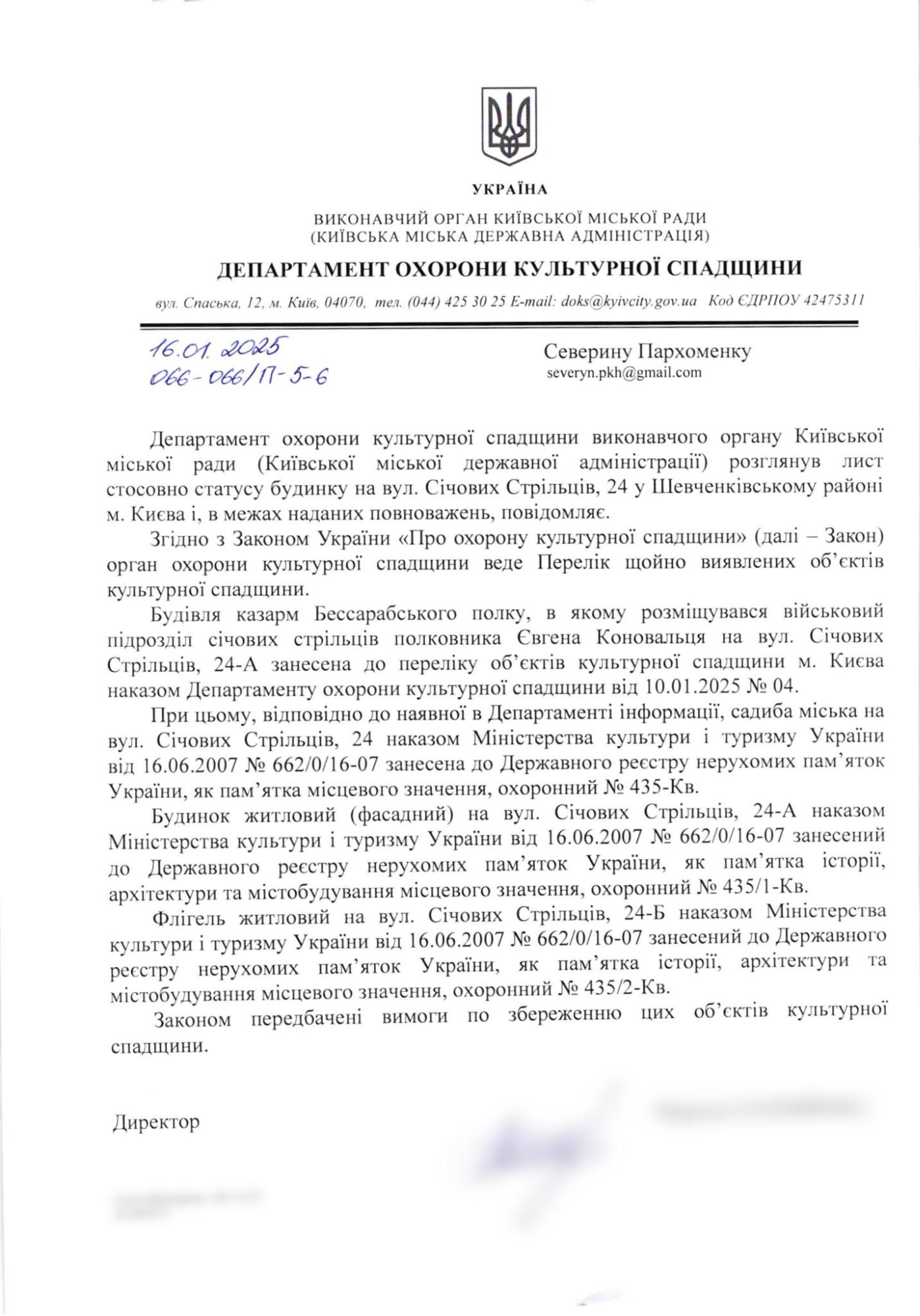

To Severyn's surprise, just two weeks later, he received a response from the Department of Cultural Heritage Protection. It stated that some of the buildings in the area already had protected status. The Bessarabian Barracks had just been granted official heritage status right between Severyn's post and their response to him.

The response from Kyiv's Department of Cultural Heritage Protection. Photo courtesy of Severyn

Now, that designation gives the barracks legal protection from demolition.

"This case was incredibly unique," Maria Panchenko adds. "Other buildings, like the Zelenskyi House, have been waiting for years — even with all the paperwork ready and submitted to the Department of Cultural Heritage Protection."

What was the barracks' situation before?

Bessarabian Barracks. Photo: Lisa Bykova

In 2003, Ukraine's Ministry of Defense signed a contract with Agropromservis-A, a private development firm. The deal was straightforward: the company would build an apartment complex on the site and allocate 25% of the apartments to the military. You can still find old plans for a high-rise building on this lot online, but the project never happened.

In 2010, the land was leased to Parker Plus, a private company. A year later, the same company bought the property outright. Several lawsuits followed, challenging the legality of the sale, but none overturned it.

Despite its historical significance, the site remains in private hands and continues to deteriorate.

Walking through the area, we see shattered windows, cracks in the walls, and graffiti covering what is left of the barracks. The only reminder of the site's military past is the Ukrainian coat of arms still hanging on the gate.

Bessarabian Barracks. Photo: Lisa Bykova

Thanks to Severyn's efforts, the barracks recently received official recognition as a site of local architectural and historical significance. However, the buildings still urgently need restoration.

Severyn says this isn't the end of the story, but at least now, the landmark has legal protection. If someone tries to do anything illegal here, activists can call the police.

Bessarabian Barracks. Photo: Lisa Bykova

"Everyone has some power to act"

During our conversation, Maria stressed that while Ukraine's laws on heritage protection still have gaps, the community itself can play a key role in preserving the city's history.

"If you see work being done near a historical building or a fence suddenly going up, ask for documentation," she says. "Request the project passport, the permit for the work, or the landscaping card. If they don't have any of these, report it to us — or call the police right away."

Photo: Zelenskyi Estate. Photo: Liza Bykova

Renovation Map has created a Telegram chatbot that allows anyone to monitor building permits and documentation in real-time to make this easier.

"But the real solution is education," says Dmytro Perov, urbanist and founder of Spadshchyna, a local cultural nonprofit. "Years ago, sorting trash seemed odd to most people. Now, it's just part of daily life. We need the same shift in mindset for historical heritage. Protecting it should be the norm. And it should be no surprise that an apartment in an old building in the city center costs more than one in a new high-rise."