What's the problem?

"All my athletes evacuated"

The sports college in Ukraine's southern city of Mykolaiv has nurtured generations of Olympian athletes. Fencing legends and Olympic gold medalists Olha Kharlan and Olena Khomrova took their first steps in the sport here, as did rowing champion and Olympic bronze medalist Serhii Biloushchenko and many other outstanding athletes.

Anatolii Shlikar, a coach at the college and the first trainer of Olha Kharlan, the most decorated Ukrainian Olympian in history, jokes:

"People tell me, 'You already have Olympic champions. Why do you need more?' But I always want more."

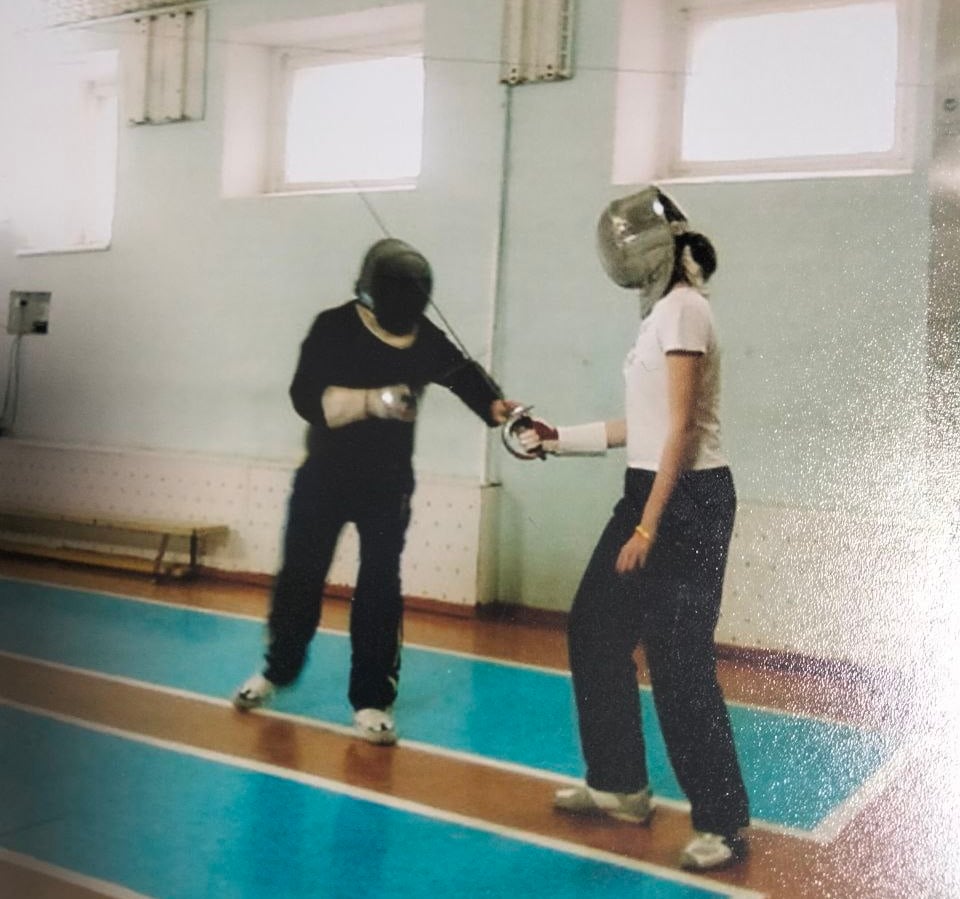

The college trainers with their students. In the center is Olha Kharlan. Photo courtesy of Anatolii Shlikar

For years, students trained hard, competed, and set their sights on new victories, until 2022, when the first Russian missiles struck Mykolaiv. The explosions damaged the college building, leaving students and coaches nowhere to train.

"The first strike hit the dormitory," recalls college director Olena Petrukhina. "Then, a direct hit destroyed the roof of the main building. Windows were shattered, doors blown apart."

The staff did what they could — cleaning debris and replacing shattered windows — but after a few more strikes, even the plywood they used for temporary repairs gave way. The ceiling collapsed, and the auditorium caught fire.

"We patched things up however we could, using whatever materials we had. There was no water, no electricity. And we stayed in that state for a very long time. All the children's and youth sports schools had to shut down," says Petrukhina.

Competing was no longer the priority — keeping the students and staff safe was. As Russian shelling continued, many students fled the city.

"I lost half a year of my life," a coach admits. "All my athletes evacuated. Every single one. None of them wanted to come back."

View of the sports hall after damage. Photo: UNDP

What's the solution?

Learning fencing through a laptop screen

For almost two years, the only way to keep training was online. Students joined lessons from safe locations, trying to stay in shape. Trainers, however, soon realized that students could not perfect sports skills through a laptop.

"Giving exercises over Zoom and trying to monitor them is practically impossible. It was challenging for the kids if we're talking about the real professional way of performing the exercises. They didn't understand what I wanted from them. It wasn't real training, it was… well, let's just say, a lot of effort went to waste," says Anatolii.

Anatalii Shlikar is a fencing coach. Fencing is all about precision — every movement matters. "Like in any sport, special exercises need to be monitored to be done correctly. If a student does them wrong, it messes up their entire technique. It's better to teach them properly from the start than to fix bad habits later," he explains.

Even now, some students still train remotely, either because they haven't returned to the city or because their parents are afraid to send them back due to ongoing security risks.

Despite fears, the college began reopening its doors in September 2023. That was made possible thanks to support from partners like the European Union and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in Ukraine, which helped rebuild the college as part of the EU4UASchools: Build Back Better project by 2024.

The initiative modernized and repaired schools in 10 regions of Ukraine, including the sports college and other schools in the Mykolaiv region. The partnership helped rebuild the college's dormitory, main facility, and sports hall. Over 80% of students have now returned to in-person training.

How does it work?

What the college looks like now

Sixteen-year-old Svitlana has been fencing for over a year. She loves the sport for its speed:

"You don't have time to stop and think. There's only now — there might not be a 'later.'"

Svitlana's family survived the Russian occupation of the Donetsk region and moved to Mykolaiv with her parents in 2023. She enrolled in the sports college and initially studied remotely. She missed in-person interaction most, so she was thrilled when she could finally return to on-site training.

She walked into a fully renovated college. "I didn't even notice it had been destroyed before. We came in, and the school was already beautiful."

The first thing students saw was the freshly painted facade.

Inside, the walls were bright white, with no trace of past destruction.

Brand-new desks filled the classrooms, and training equipment was in place.

One of the most important updates was the bomb shelter, now able to hold over 400 people. During air raid alerts, students go underground and continue lessons without interruption.

The college trains students in grades 8–11. Many are from the Mykolaiv region, while others are displaced from other areas. Fifty-three of them are on national teams that represent Ukraine in international competitions.

When fencing becomes more than just a sport

Coach Anatolii has been in the profession for over 40 years, half of which were spent at this college. He has trained many elite athletes, including Olha Kharlan.

"She was a tomboy from the start. She wasn't afraid of anything — not falling, not climbing things. She was like a little hurricane. And she still is. Just look at how she fences. It's like a motor running non-stop. Speed, power — she's got it all," says Anatolii.

According to the coach, fencing is a challenge sport, where you need both technique and self-control. You need to feel the distance, your speed, and your opponent's speed. If you can't sense one of these things, you won't win. That's what Anatolii always teaches his students.

When Russian forces destroyed the college, they didn't just take down a building. They took away a place that meant everything to Anatolii.

"I walked around with my head down, thinking, 'That's it. My life is over. Everything is lost,'" Anatolii admits. But now, the hall is once again filled with the sounds of clashing blades. Student groups are at full capacity. He says:

"It feels like I've been reborn. My students and I often stay late after practice, even when it's time to go home. My wife asks, 'Why are you coming home later and later?' And I tell her, 'I'm working, not slacking off. I just want to work.'"

The EU4UASchools: Build Back Better project is implemented by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in Ukraine with financial support from the European Union.