What is the problem?

People whose relatives are currently soldiers who have left home to defend Ukraine often remain invisible to society. Even their loved ones may not fully understand their experiences, which can increase feelings of loneliness and isolation.

What is the solution?

In the Western Ukrainian city of Uzhgorod, psychologist Tetyana Matviychuk and craftswoman Tetyana Allahverdiyeva launched a project for people waiting for their loved ones to return from the war. The Povjazani initiative is a non-profit social project designed to support people waiting for their loved ones to return from duty, and help them find like-minded people.

How does it work?

"Now we are all connected by one thing — a state of waiting"

Tetyana Allahverdiyeva and Tetyana Matviychuk. Photo: Dariia Getsko

Tetyana Matviychuk is a psychologist, volunteer, and military wife. Tetyana Allahverdiyeva is a master of weaving. Both women are well aware of the state of expectation and stress that becomes a constant companion of people whose relatives and loved ones are now at the front.

"It all started with a 'let's' — when we met in the summer, we shared the experience of waiting for loved ones to return from war. Tanya proposed we do something for people like us," Matviychuk recalls. "After all, we both know how difficult it is to wait. We discussed the format, name, and other details for a while. In just a few months, we created an Instagram page and started talking to the world about our idea."

The project, which started this fall, was decided to be called Povjazani – "because now we are all connected by one thing — a state of waiting," says Allahverdiyeva.

The idea of the social initiative is simple: the project's initiators decided to collect scraps created by the hands of those who are waiting and make a canvas from them, which will become a symbol of those who worry about their dearest every day. At the same time, it is to collect the stories of the authors of handmade scraps. Patchwork can be made of any material and in any technique. The project is not limited by time or geography — a scrap can be sent by post from anywhere in Ukraine. The only condition is that it must be 10×10 centimeters in size. The project has an Instagram page with a questionnaire to help you send your scrap to the project. The project is open to both adults and children.

"People send us these scraps and fill out a questionnaire, in which they optionally share their story about those they are waiting for or have been waiting for, as well as what they would like to say to the world with this scrap. There is an opportunity to do it anonymously or not anonymously so that we can share these stories," the project's initiators explain.

"You can let go here"

"You can let go here" is an inscription in the office of psychologist Tetyana Matviychuk. Photo: Anna Semenyuk

Matviychuk created a placard with this inscription and placed it in her office. In Uzhgorod, she conducts support groups for women waiting for their loved ones. She knows very well that although they are in relative safety away from the combat zone, they live the war every second and need to share their emotions and experiences.

Those who send scraps also rarely express a desire for their story to remain private — for many project participants, it is vital to be heard. Without the cliché of "holding on," looks of embarrassment, comparisons, and depreciation.

Therefore, scraps are often sent to Povjazani with stories behind them:

🧶 I want to tell you about something that I haven't told anyone. My husband has been at war since April 2022, and sometimes, it seems that I have already grown accustomed to such a life. But it is so hard to accept and even harder to say it out loud. When my husband came on vacation for ten days, I couldn't fall asleep next to him, as I was used to sleeping alone. I still love him, and we have a good relationship. We solve all issues together regarding our daughter's education and repairs. It is also very difficult to hear how relatives or friends whose husbands are at home plan vacations together, trips to a cafe, birthday parties, and rest in the park – while I seem to be reliving the same day since my beloved went to war.

🧶 He charmed me with his authenticity and sincerity. He surprised me. He loved so sincerely and devotedly. He became what I didn't expect: an incredibly cool dad for our sons and such a great role model for them. His hands hold the strongest, and he throws his sons up the highest. His shoulders are always ready to be leaned on or to carry his sons on top. His hands shook twice in his life: when he was mobilized and when he was sent to Ukraine's east. My hands shake every day: when I don't hear from him, when the phone is silent, and when I see all the news, when a child asks about when their dad will come home; why other have a dad who comes home, and his dad doesn't. We will wait, and if not, I will be enough for the children. I can, but I don't want to. I love him madly, and I am waiting for his return. Let everyone wait for their heroes to return home.

🧶 Our relationship began and continues at a distance. It's unbearably hard, but at the same time, I'm very happy because our relationship is healthy, sincere, warm, and tender, and we love passionately. He volunteered to serve and is a man worth waiting for — caring, loving, understanding, supportive, handsome, and simply the best. He is the first man in my life to whom I dedicated a tattoo and to whom I write poems. I thank him for the opportunity to live in a free country, sleep in my own bed, drink coffee, and feel. Love and pride for him are stronger than fear. I love him. I'm waiting.

This is only a small part of the stories that accompany the scraps of the Povjazani project. They are one of thousands of stories of lovers, married couples, parents, and children separated by war. But only physically. Spiritually, it united everyone even more and made it clear that nothing is more valuable than family.

The authors of the stories also write about how important it is to keep the faith and, above all, to leave room for love and kindness. They write thank you letters for the community and the project that saves human hearts.

Our strength is in unity

Scraps-stories of the Povjazani project. Photo: Tetyana Matviychuk

"We launched the project in September and set the first deadline for October 14, but now we have abandoned that because this project will continue as long as the war lasts," says Matviychuk.

So far, more than 20 women from all over Ukraine have sent scraps to the project. Patches are made using various techniques: embroidery, crochet, knitting, weaving, and sewing.

"This is art therapy. Any handicraft calms, quiets down, helps to notice yourself and not hide behind a pile of daily tasks. This is how memories and emotions are organized," says Matviychuk. "Have you noticed how it happens with cleaning? Bringing order to the outside, you also bring it inside. In the case of needlework, the same principle applies. Our great-great-grandmothers gathered together to embroider, sing songs, and talk — it was a kind of group therapy. People knew there is strength in unity and collective work long before such a science as psychology arose."

Matviychuk adds that what the project needs most today is publicity, so that as many of those waiting as possible can join it and find support and understanding – which is often lacking.

The project is not limited to an online format. Matviychuk and Allahverdiyeva already had one offline meeting in the workshop with Uzhhorod project participants. Women wove, talked, got to know each other, and committed to holding more such meetings.

Bound by fate. Connected by hearts and a sincere desire to be together

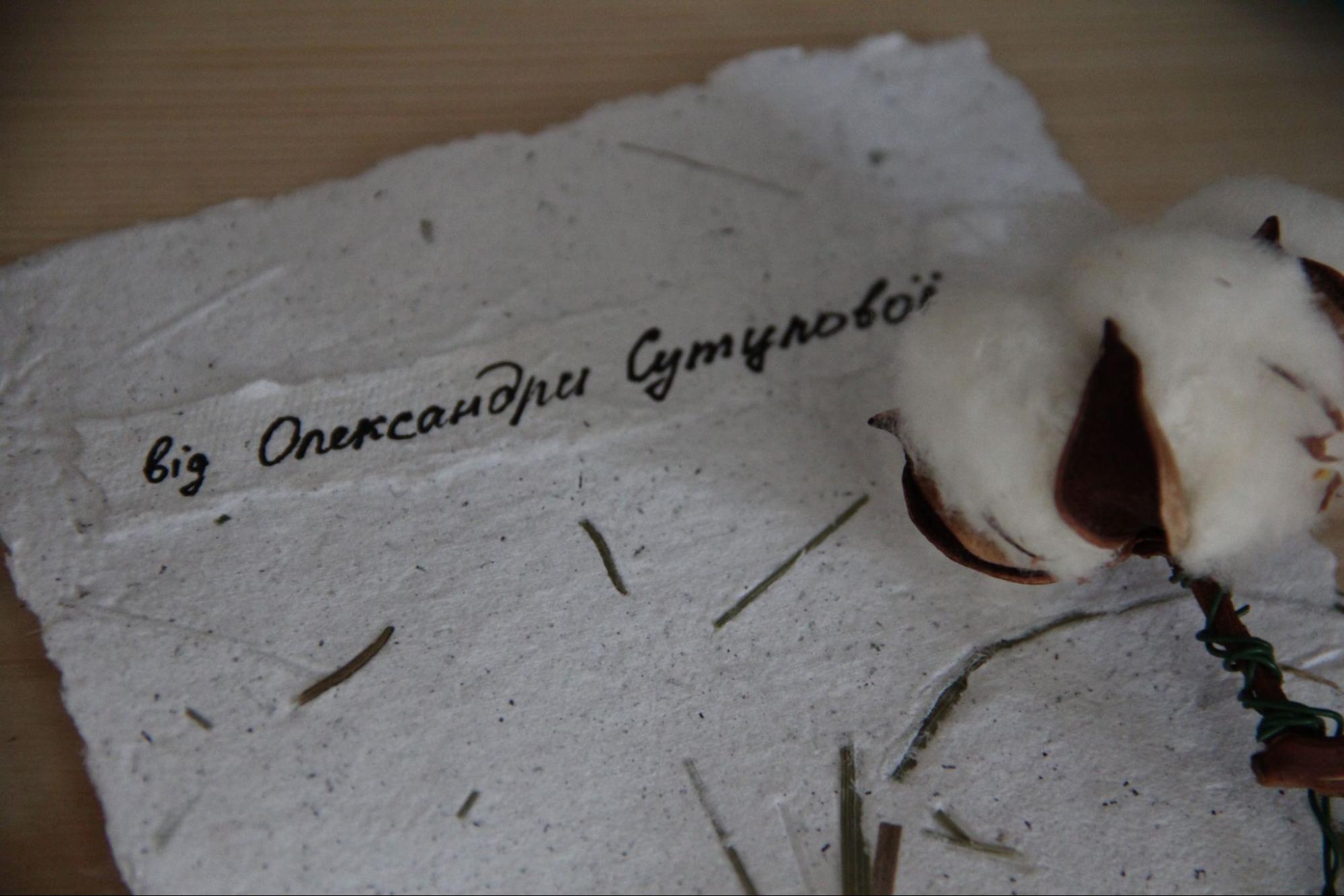

A letter-story from a participant of the Povjazani project. Photo: Anna Semenyuk

"Connected by war – perhaps this is the most apt way to say it," says Matviychuk. There are different levels of human interaction, but the Povjazani project is primarily about national identity – that is, for all who consider themselves Ukrainians, who fight for the values of freedom and humanity, who are a reliable support for the soldiers. It is difficult to generalize why people join the project. Apparently, they are looking for support and want to be heard. "Remember what unity was like at the beginning of the full-scale invasion? Now, this is very much lacking," Matviychuk shared with Rubryka.

Matviychuk says that for her personally, this project became a way to find like-minded people.

"Also, I am increasingly aware of how differently we experience similar things. I have been learning to notice commonality and difference and accept unsolicited advice throughout the war," says Matviychuk.

What's next?

Photo: Anna Semenyuk

The founders of the Povjazani project have not yet disclosed what kind of product or canvas they plan to create when a sufficient number of scraps are collected. The authors of the social initiative want this common canvas not to belong to one person. They say it should be a reminder that the war continues, and many, many people are waiting or have lost loved ones in the war.

"Since the canvas lives and is constantly supplemented with new scraps, we do not know when it will be ready. While the war continues, we collect people's stories, giving them their place and time. It will be an art object that will demonstrate the experience of the war, at least a tiny part of it," says Allahverdiyeva.

Matviychuk adds: "It would be great if as many people as possible participate in the project. It would be a kind of representation of how many people were affected by the war. But if at least one person, having joined, feels relief and support, it was not in vain."

Even more useful solutions!

Povjazani is a project designed to support anyone who has ever waited, and help find those who understand. Photo: Dariia Getsko

Where to get strength and resources, to look for support for those who are waiting? To this question, Matviychuk offers: look for your people, those who respect and are interested in your life, and do not devalue or give unsolicited advice.

The psychologist shares that for her personally, such people become a source of strength and inspiration: sincere, honest, open. Those who do not pretend that everything is fine – but can let others just cry if they need to, get angry, and feel relief together.

"I am definitely a person of sense. I am not interested in doing something solely for the sake of income. There is a spark in everything I do. It inspires and motivates me. When I get tired, people appear who, with their words, looks, and actions, make me feel better. This gives strength to move on. I want the chain of support not to be broken and for as many people as possible to see that they are not alone. Piece by piece — that's how a large canvas is made – the canvas of our stories," Matviychuk shares.

Shirtless: how the forum theater helps displaced women in Poltava to start living again

"Я стала батьком для сина й чоловіком для мами": як українкам за кордоном подбати про себе, дбаючи про інших