"I lived like Mowgli in bird colonies" — how does the nature reserve fund employee's day look?

On the occasion of the Day of Ukrainian Natural Reserve Fund Worker: Ivan Rusev, a scientist, biologist, and natural scientist, talks about equipment for ornithologists then and now, the war against enterprises greedy for natural resources, and why he goes on an ornithological expedition with a gun

Ivan Rusiev, head of the NPP "Tuzly Lagoons" research department. Photo: Andrii Horb

Our editors met Ivan Rusiev a year ago when we were telling the story of Red Book pelicans being released from a restaurant where the birds had been delivered by poachers. Then Ivan held the position of director of the Tuzly Lagoons National Natural Park, but administrative work isn't at all what the scientist wanted to do.

Ivan Rusiev is a biologist who defended his Ph.D. and doctoral degree in Ecology twice and is sincerely in love with birds. When he starts talking about volatiles, the scientist, who looks like a researcher who's just stepped out of the film, lights up:

"Have you ever held a pelican in your hands? Now, if you take a goose or duck, they're plump, and a pelican is an air formation, a cloud! Nature did this to make its flight easy and smooth. It has huge air voids between skin and body, bones are porous…" it seems that he's ready to talk about birds for ages. Even the ceiling in his house (we look at Ivan through the screen, since our conversation took place via video) is painted in the color of the sky with the clouds floating.

— You're a biologist, but you pay a lot of attention to birds, although there are other animals in the park. Why is your focus mainly on ornithology?

— Birds are my love, my path. The Tuzly Lagoons is considered one of the most important wetland sites of international importance; the sites are protected by the Ramsar Convention, the first one signed on the planet! Since Tuzly Lagoons are wetlands of international importance for birds, we pay primary attention to them, although other organisms of flora and fauna are also under the sights of our park's research department. These are land mammals, vertebrates, flora, insects, and fish, naturally.

For the last 2 years, Ivan Rusiev had been the director of the national park. He considers the struggle for the safety of limans his mission. However, he left his leadership position:

— I'd been the director for 2 years, and then I wrote a resignation letter where I said that the ministry was corrupt, like the entire system, that I didn't want to work in it, and I'd do what I like, and work in science. Therefore, I left and asked the ministry to appoint my deputy, Iryna Vykhristiuk. She became an acting head of this park.

— I was told that natural science activity is more to your liking than administrative. Tell us, what are you doing as a scientist and as a worker in nature conservation?

— Since my student years I've been engaged in science. It's my profession. My hobby is to explore, observe nature, analyze what's happening and make recommendations. That's how I worked until 1981 when I was young and was a new researcher. But when I got to the Ural Sea, saw an environmental catastrophe, I made a decision: along with scientific activities, I'd deal with issues of nature conservation. And here we are at the junction all the time: if a scientist isn't engaged in implementing his developments, in particular, in my path, nature conservation, then it's pointless. You write scientific articles, collect facts, but you still need to create some kind of result. And so I, having left a managerial position, took up real science: we're constantly observing the migrations of birds, their numbers during the nesting period, wintering during the critical period, and these data form the basis for the analysis and then are entered into the annals of nature. This is the main document that any national park, any object of the nature reserve fund, prepares so that it will remain for centuries. In years, people will see what species lived here, what their number was, how they moved.

— We have an ornithologist who monitors these bird phenomena and conducts special scientific research, for example, when we need to track how birds fly during the winter from their cribs to feeding grounds, etc. That is, it's a detailed sequence of algorithms that scientists need to understand a particular phenomenon in nature. We have an entomologist who observes insects in nature: when they appear, what kind of cynology they have, how the weather affects them. There is a mammalogist who studies land mammals — badgers, foxes, jackals, raccoons, all kinds of small animals — and, of course, there's an ichthyologist. Unfortunately, we don't have a "complete" ichthyologist, since specialists of such a narrow specialization are in Odesa, while a scientific department specialist and a laboratory technician perform his functions. I want to say that ichthyology is, on the one hand, an interesting science, but on the other hand, it was very corrupt in the Soviet era and is still corrupt now, because they do everything in the fishery system to make more justifications for catching fish. And in our park, we are needed, first of all, to say that these species require protection, they cannot be caught during this period because there aren't very many fish, or the environment isn't suitable, and we collect information, although it's still a little, to find out what the fishing limits for local fishers may be. Naturally, the big direction is vegetation. There are more than 800 species, growing in different conditions, ranging from a sandbar with a desert climate, to an empty area where they're artificially planted, and aquatic plants that require tremendous attention. Therefore, in our park, there's a wonderful specialist, Olena Popova, who also works at the Mechnikov Odesa National University. She provides a very competent scientific product in this direction.

What does a natural scientist's day consist of?

— How does your day in the Tuzly Lagoons look like?

— A scientist's day, you know, is like of a free artist. He can rest and ponder hypotheses. For example, how did this bird appear in our area? Let's say a flamingo; how it ended up in our limans. And then the scientist begins to test these hypotheses: how can a flamingo fly from nesting places in Turkish Izmir? What brought it here, what wind flows… And then these hypotheses are tested in practice: is it really so? As an investigator investigates crimes, a scientist investigates nature to draw some conclusions about changes in nature or its stability, if it doesn't fundamentally change.

— Don't scientists sit in ambushes for hours, watching birds and animals through binoculars?

— As a student, I lived like Mowgli in bird colonies. I took some food with me, mainly Soviet canned food — sprat or gobies, bread, which quickly became stale — and lived for weeks in bird colonies. From morning to evening and from evening to morning, I knew what they were doing: how they go to bed, how they communicate with each other, how they feed their chicks. Now, it's not necessary, since there are other tools, say, camera traps. Today I put a camera trap in a colony of birds, and in a day or a week I can come and take all the information about their life; it will be on my flash drive, which greatly simplifies the work of a scientist. But I like being in a bird colony, I can just live there, for hours, days, and weeks! But the older you get, and the more you know, the less you understand, because nature is so complex with its connections and its versatility that human knowledge and the ability of one brain isn't enough to figure it out. You get the facts, but you immediately raise a lot of questions: why it's happening this way and not otherwise. Therefore, the more you research, the less you know, just like Socrates.

— What's in your backpack when you go on an expedition?

— The first thing I put in there is a gun. I need it for self-defense. I put a pepper gun to defend against possible attacks by poachers. After all, we not only research but also participate in the operations of the Security Service; it's an organization managed by a director, and scientists aren't part of it. I performed this function when I ran the park, and now, with my scientific activities, I do journalism, and I have the right to carry weapons, which I always keep in one of my backpack pockets. In another section, I have cameras, from professional Canon to the simplest, long-focus and short lenses: everything that helps capture the phenomena of nature. In addition, there's a police camera, which is easy to install on a jacket. You walk, and it takes pictures and records the phenomena; naturally, I also have various camera traps I place; some kind of field clothes, but, you know, we scientists are such fans that sometimes we forget to change clothes on time… I walked through the swamp, got out, dried up. So I have few clothes. I also carry a mat with me, some flashlights, and a voice recorder. Previously, we had notebooks for taking notes, but now you can voice record everything you see, and then decipher it in the laboratory. Everything is very simple and modest.

About pelicans and modern technology

— Rubryka is following the situation with Alibei and Alkalia, whom you rescued last year, and we know that both pelicans have already flown away. What do you feel? What news about birds should we expect next?

— When I release birds to this place, if the landscape permits, I put camera traps so that I know what's happening there without me. Thus, I learned how the stork Robinson returned to us, how the wild goose left us, and then returned. I also learned about pelicans from camera traps. Now I've taken all the traps for reinstallation, and in the next few days, I'll put them back to find out if Alibei and Alkalia appear in the places where we released them. On the other hand, we have a network of observers, volunteers who can inform me where they saw the birds, as it was with Alkalia when she ran away and fishers found her. I hope nothing will happen to the birds. I'll see them soon and write about it.

— Yana Bobrova from Peli can live said that they can even buy GPS weights for birds to track their movement. What other modern technologies are used in the park to observe and watch animals?

— When I was a student, I dreamed of finding out where the birds I "communicate" with fly away to. And during my student years, living in bird colonies, I managed to ring 5 thousand chicks with aluminum rings, which I received from the Moscow Ringing Center. They were given to the Mechnikov University. We received them, filled out the statements about birds we ringed. And then ringing was the only tool; it appeared 100-200 years ago in Germany. In this way, it was possible to study the migration of birds, receiving "returns"; data on where other bird watchers caught this bird was sent to the address indicated on the ring. Then I received about 40 returns from African countries — Chad, Mali, the Republic of Niger — the places where our birds go winter.

So I got a lot of information about bird migrations, routes through Italy and France. There were even birds that, it would seem, were supposed to fly south in the pre-winter period, and they flew north; they were found near Kyiv and Zhytomyr. At that time, through the rings, I received objective information about where the birds live. The world has changed today. I used to spend a lot of time living in colonies, but now I can set up camera traps and be in the distance.

Now rings are used less and less often, more often resorting to chipping. In recent years, we've used them with our Bulgarian colleagues on the red-breasted goose, a rare species of bird that nests in Russia, in the Tundra, but arrives at our territory for the winter. We find this out with sensors. But this method is very expensive for Ukraine. Usually, ornithologists receive grants to buy chips. We'd also like to get them for pelicans, but in this case, we were a little late, since we had already released them, and now it'd be very hard to catch the birds because they have already begun to flutter, they're flexible and nimble. Even if we get such chips, we'll attach them to the chicks, because it's easier.

Fight for limans. How the work of scientists turns into a real war

Working in the National Nature Park involves not only exciting observations and photo hunting. It's also a struggle for the conservation of the resources, which Ivan Rusiev is waging with the local company Granit Service Cooperative, which is engaged in catching fish.

Ukraine has signed several conventions, parks and reserves are a tool for their implementation. These are the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands, the Bern Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats, the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species, and the Convention on the Protection of Biodiversity. At the legislative level, all these objects must be protected and every effort should be made to preserve them. Tuzly Lagoons are especially in need of this now, in the hot summer period. To understand what role a person plays in this matter, we asked Ivan Rusiev to explain how limans "work."

The beach at the Tuzly Lagoons NNP in its protected area (the sea on the left, the reserved lakes of Academician Yuvenalii Zaitsev on the right). Photo from Ivan Rusiev's Facebook page

— You often write that you open liman access to the sea, clearing the sand with tractors "with a fight." What for?

— The Tuzly Lagoons are a formation, developed due to the influence of two enormous forces: small rivers from the mainland that flow into the sea, and the sea itself, which props up these rivers with its powerful waves. Thus, limans can live by filling up from two sides, taking water from the sea or rivers. In the state, as now, when the rivers practically don't give water, it comes only from the sea. And if it doesn't come there from the sea, limans will dry up due to crazy evaporation. Our task is to maintain water exchange in the limans, because if there's no water in the limans, or they're overflowing, then migratory birds, settling in shallow water, will simply stop being there, they'll leave. That's why it's so important to maintain the hydro mode. On the other hand, we need to guarantee the constant migration of the hydro-biome: at the beginning of each summer, the mullet swims into limans, feeds, and spawns in them, and at the end of summer and autumn, goes back to the sea in mother flocks.

Fishers, helping park staff to restore water communication between limans and the sea. Photo from Ivan Rusiev's Facebook page

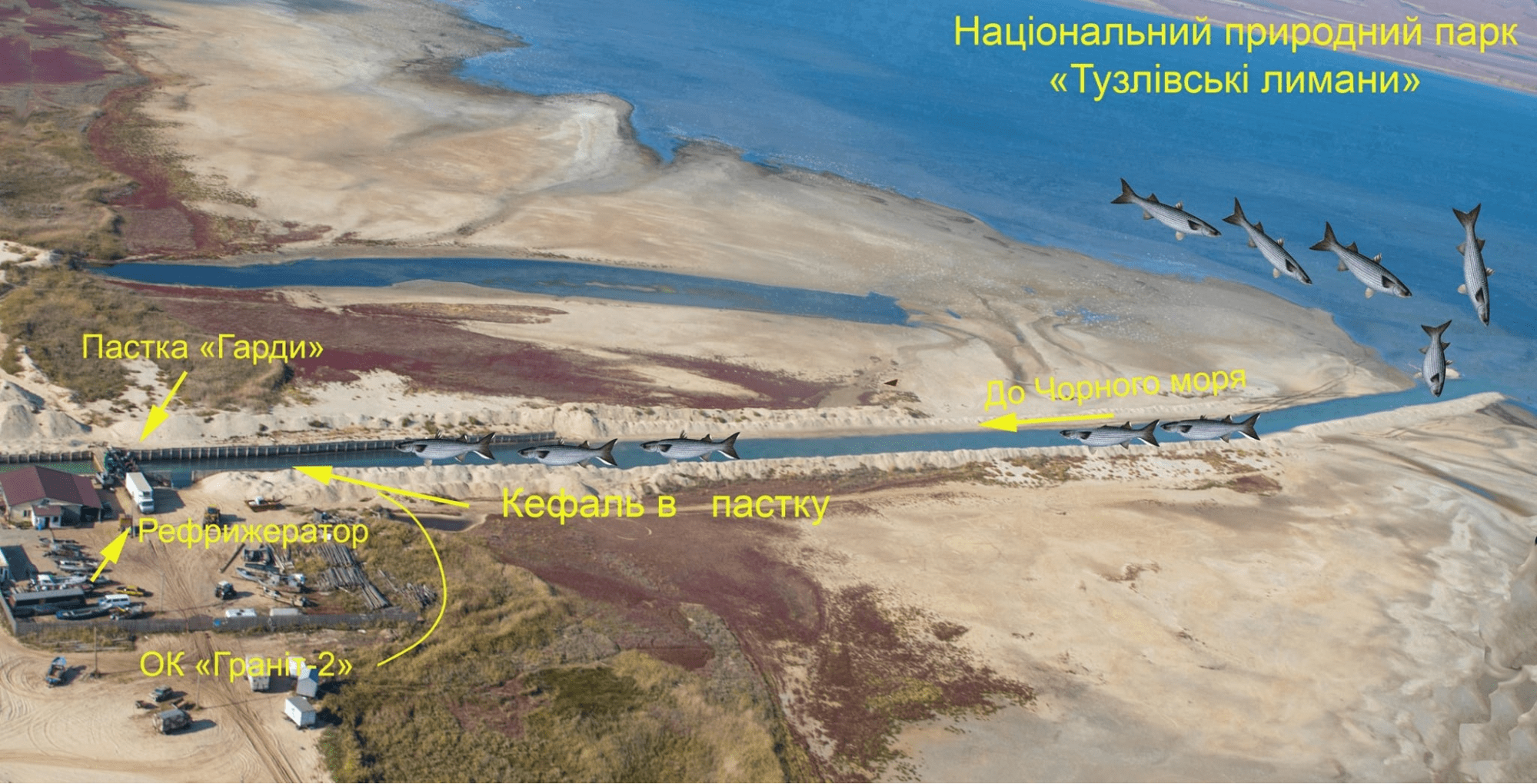

— Granit Service Cooperative is a company, created to usurp all water resources. Together with the park's former management, they created this company and agreed that the park and Granit would manage these resources together. To prevent the fish from swimming out of the limans, Granit Service Cooperative closes the channels between the sea and the limans and leaves a small channel through which the fish are caught when they should come out. The local population has no access to fishing, and Granit Service Cooperative received a full monopoly on fishing. The park's task in this situation is to discourage such illegal activities. To do this, we collect money, look for resources for fuel and equipment so that limans have normal water circulation. It's important for all organisms and animals.

However, Granit Service Cooperative interferes with the conservation of the park's ecosystem. According to Ivan, employees of the enterprise arrive at night and close opened channels. They create an aquarium from a huge reservoir, thirteen limans, from which there's only one exit, their sleeve.

— And they do it with the support of the law enforcement system. Everything that has accumulated in the summer is trapped. They catch all fish, big and small. If this continues in the future, there'll be no resources. We cannot tolerate such a greedy attitude towards resources.

The struggle goes on constantly, and Granit Service Cooperative goes to extremes; bandits disguised as border guards attack scientists, and they have to defend the life of fish and birds using physical force.

Investigations aren't being conducted properly, and according to the scientist, the entire corrupt system exists only because of the trafficking of illegally obtained resources. Although the park's employees have collected an enormous amount of video evidence, and witnesses can confirm everything that is happening, the case isn't moving forward.

— The only institution not tied to these schemes is Tuzly Lagoons NPP. We managed to assemble a team, not interested in these profits, and our only goal is to fulfill Ukraine's international obligations to the international community. We're not indifferent to the fact that such fragile creatures live with us. Gerald Durrell [English natural scientist and writer of the early 20th century – ed.] said: "Animals have no deputies, there's no one to protect them."

— If the Ukrainian law enforcement system isn't able to protect limans, maybe international ones can? Have you appealed there?

— I have experience in contacting international organizations. When two years of management didn't give effective progress in normalizing water exchange in limans, I wrote to the Ramsar Bureau in Switzerland so that they'd draw attention to the fact that here are Ramsar sites of international importance, which a million birds fly through, and then settle in Europe, so that they help us to normalize the situation. Then they wrote to the Cabinet of Ministers, then the letter goes down to the Ministry, from where the usual replies come. If the European Commissioner came here directly, investigated the situation, collected primary material, and made a conclusion, they would've seen completely different data. And so, the Ministry says that everything is done within the law. Everything turns in a circle and returns to Ukraine, where officials don't understand what's happening on the ground, are corrupt, and perform the tasks of local oligarchs.

— Are there any positive forecasts?

— I'm an optimist in life, otherwise, I wouldn't have been engaged in environmental protection for 40 years (Ivan laughs). Of course, there are positive forecasts, the entire world is moving towards making society aware of the value of the natural environment and the obligation to protect it. When I was young, I knew that the capitalist world destroyed the Rhine River in Europe [in the 1970s, the Rhine River was so polluted by industrial enterprises that salmon disappeared from its waters – ed.]. But time has passed, and Europe shows that the standards are very high: if you have an enterprise, then the wastewater must be cleaner than the chosen one, otherwise the legislation will simply destroy you. That is, sooner or later, this process will come, our society in this, as in many other industries and technologies, lags behind. Not because we're weak — we have a lot of smart people — the system that kills free competition doesn't allow us. Sooner or later, Ukraine will embark on this path and get out of the collapse that Russia has created for us, and the time in which we live. We try to be an example that it's necessary to fight for the protection of resources.

Little tradition

— We've already come to the end of our interview, our little tradition remains. What book would you recommend our readers to read?

— Unfortunately, I read few fiction books because I devoted a lot of time to studying nature. After all, life is so short that I didn't have enough strength to waste time on everything. Instead of watching movies, I looked through the lens of a camera and camcorder. My favorite book is an entire series of books by Gerald Durrell. I read them in my youth. This natural scientist dedicated his life to researching African wildlife, and in his books, he tells different stories from expeditions. I think his books will help young people get on the right path. I see a stack of National Geographic magazines behind you [we interviewed Ivan via video, and the scientist looked into my office through his laptop screen – ed.]. It's an excellent publication, made with high quality, telling different stories about the world. It could be very helpful for young people too.

How to help the park?

On the website of the national park, there's a volunteer questionnaire that anyone can fill out, choosing the direction, which they want to work in: scientific, educational, recreational, security. The park contacts a volunteer at a certain period and invites those who wish to help preserve the natural wealth.

Both single "fighters" and entire teams come to such events. For example, in 2019, with the funds of activists, a house was built, which serves as both a tourist center and a guardhouse (it is called "Cordon" in the Park). It's small, only 30 square meters, which contain 3 rooms: a kitchen, a bedroom for employees on duty, and the third room serves as a visitor center for tourists. A birdwatching tower was built right on the roof of the house, which gives a special charm to Cordon. And one audit company even organized a "clean-up" for its employees in the park. The corporate team has built an entire birdwatching bungalow.