What is the problem?

The problem has existed for ten years

In February 2014, Russia attacked Ukraine — then the blow came to the Luhansk and Donetsk regions, as well as the Autonomous Republic of Crimea. Ukrainians were forced to leave their homes en masse and seek refuge in other parts of the country. They left everything behind: housing, work, and hope for a good life in their hometown. Some of them had older relatives and close people left in their native lands, whom they never saw again after saying goodbye.

Internal displacement was not new for Ukraine, but the society was not ready for such a scope. According to the UN, there were about 1 million internally displaced persons in 2014, which only grew yearly.

Part of the exhibition Chronicles of Evacuation in the Gallery of Protest Art of the Maidan Museum from the charity fund East SOS.

With the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the situation repeated itself. Only now, there are not a million IDPs in Ukraine, but almost five. And they all need support.

Oksana Kuyantseva, board member and coordinator of the communication department of the East SOS charitable foundation, which has been dealing with the problems of IDPs since 2014, notes that the main issue is the integration of the newcomers into the host communities, in particular through employment.

Oksana Kuyantseva. Photo: FB

Kuyantseva emphasizes that due to bad conditions in a new place, Ukrainians often choose to return under shelling: "It is important for us as a society to think about why this happens. Most likely, they could not integrate in the place where they were, and as soon as the opportunity arose, they were ready to return even to broken cities."

What is the solution?

Indifference. Changes. Love for one's family

On the same wave of the rise of civil society, which inspired the creation of East SOS, the non-governmental organization Poltava Platform was formed in Poltava. Its co-founders — Oleksii Serdyukov and Dmytro Nalyotov — later in 2018 started their organization Zmist Poltava.

Step by step, they launched a news site and opened a cafe-bookstore — a social business where two to five hryvnias went to local charity projects from every book and cup of a hot beverage. It was something innovative and unusual for Poltava.

Zmist editorial office.

With the start of a full-scale invasion in 2022, Zmist was reformatted entirely to cover the needs of the military. "The cafe did not stop working even during the acute phase of a full-scale invasion — we were fully staffed. We went into the bookstore, and there was complete chaos: people were wandering, machinery was standing, and armored vests were stocked," recalls Alisa Kutsenko, the head of the NGO.

Kutsenko is holding a book about the history of Poltava.

At the same time, resettlers from more dangerous regions came to Poltava daily. The team remembers how the newcomers spent the night in cars, did not understand what was happening, and the city council could not quickly process applications. As of the end of 2023, 186,000 displaced people have been registered in the Poltava region, according to Dmytro Lunin, head of the Poltava Regional Military Administration.

Such an influx of people who needed shelter and adaptation in a new city gave impetus to a new initiative of activists — the Zmist IDP Adaptation Center. Director Oleksandr Skrypai says that now it's not just about adaptation — Zmist helps IDPs to integrate in Poltava, move away from the status of visitors and become locals.

How does it work?

A person needs a person

The day is gradually ending, but not at the Zmist IDP Adaptation Center — everything is just beginning here. The doors open repeatedly, and smiling women enter from the cold street. During the week, they collected many stories that they wanted to share.

Participants have tea before training.

Magazines, newspapers, scissors, and paper are spread out on the table — today, the center's psychologist prepared something exciting and creative for the participants. While everyone is getting ready, Ilona Oryshchenko, head of the center, says: "At the center, we work with socio-cultural and economic adaptation. Socio-cultural work includes various leisure activities: museum tours, hiking, educational direction, and health school with various lectures. Economic one involves the employment of internally displaced people and retraining project".

Ilona Oryshchenko.

Oryshchenko points to homemade snowflakes hung all over the room: "We made them ourselves for several days. We really wanted to create a festive mood for our participants." People of different age categories come here, but they all have the same need — socialization and a good time in a circle of pleasant acquaintances.

Olena is an IDP from the Kharkiv region. Today, she came to the center with her son. They moved to Poltava after her hometown of Chuhuiv began to be shelled daily.

"At first, we were in Ternopil, then in the village. We were very well accepted, but unfortunately, the child got bored, as the village had no activities for children. My sister lives in Poltava, and in general, there are many centers for children's entertainment there. The child needs to be developed and given opportunities despite the war," Olena says.

She describes her native Chuhuiv as a small and cozy town that was a frequent tourist location before the war. On February 24, Olena was at work in Kharkiv. She recalls she did not understand the scale of the problem when the war started.

After work, Olena went home, but there was no more transport to Chuhuiv, so she left on foot under the explosions. Mother still managed to find the last train heading towards the city, but it also stopped halfway — the driver announced that the tracks were mined. Then, they resumed their trip on foot. "It was horrifying when you walk, and the forest around you merges with people. Everything explodes, and you do not understand what is happening. I called my sister and asked her to take my child."

For some time, the family hid in the basement; later, an acquaintance took them out of the city. Olena says that the Russians fired at the cars in front of them. Many people were evacuated by volunteers.

Olena recalls it was morally difficult in the new place, but the family was lucky with people on the way: they supported, hugged, reassured, and helped. Olena laughs that she learned to chop firewood and collect water from a well in the village. The son and other children made DIY ant-tank hedgehogs from sticks and checkpoints — "memories will last a lifetime, no matter how scary."

Olena learned about the Adaptation Center from social networks. She says that it was difficult to dare to come. She was silent at the first training. However, the center has already become a safe place for her just after a few visits. In addition to participating in therapeutic meetings and consultations with a psychologist, Olena plans to apply for a job search project.

Hands are busy, and the mind is resting

The center's team believes that work gives the displaced people the needed routine, stabilizes their morale, and helps them adapt. In addition, it is also obviously about financial security, so they no longer depend on donors or humanitarian aid. That is why one of the center's priorities was economic development — helping IDPs with employment.

Alisa and Vita talk about their experience.

First, a survey was conducted among the displaced people on whether they needed a job or whether they planned to stay. Subsequently, a program was developed, according to which HR volunteers interviewed those willing to determine skills, level of education, and values. After that, the center offered people suitable jobs. More than 30 Poltava enterprises have become partners in providing jobs for IDPs, including large businesses such as Aurora, ATB, Wellmart, and others.

HR volunteers were recruited gradually. Each of them wants to help while they can. Kutsenko says: "We understand when they say they can't do it anymore. Then we invite other people." So far, there have been no problems with those willing to help — someone always responded.

Vita Molka, HR manager at Zmist, recalls that at the beginning of the project — from December 2022 to the summer of 2023 — there could be up to six interviews with IDPs daily. The number has decreased — Kutsenko suggests that this is because those who wanted to have already found a job in two years.

However, it was not without difficulties. For example, it is difficult to find a job for metallurgists and former mine workers — where in Poltava can you find such vacancies? Therefore, Zmist created another work area — retraining IDPs for new specialties. The initiative, carried out jointly with the International Organization for Migration, helps resettlers retrain as IT testers, graphic designers, beauticians, and baristas.

Molka explains: "There are women who cannot find work here. Their husbands are at war, they are raising a child alone, they don't know who to leave them to, or they have children with special needs. They simply have nowhere to go. It will be a way out for them if they undergo retraining, for example, in manicure and can work at home and earn at least some income."

The HR manager mentions another successful case where retraining helped realize a long-standing dream. One of the IDPs studied at the university as a tester. Unfortunately, his father was diagnosed with cancer and could no longer continue to pay for his education. He worked at a gas station, earning money for treatment. After moving to Poltava, he also started working part-time as a loader. When he came to the center, he said he still wanted to study IT. His father is bedridden, so he could take care of him and work at home at the same time. After completing his studies, the center provided him with a new laptop for work.

Fifty people graduated from the retraining program and now have practical equipment for a professional start in addition to knowledge and skills. The program was in great demand, so Zmist plans to relaunch next year.

"I belong here"

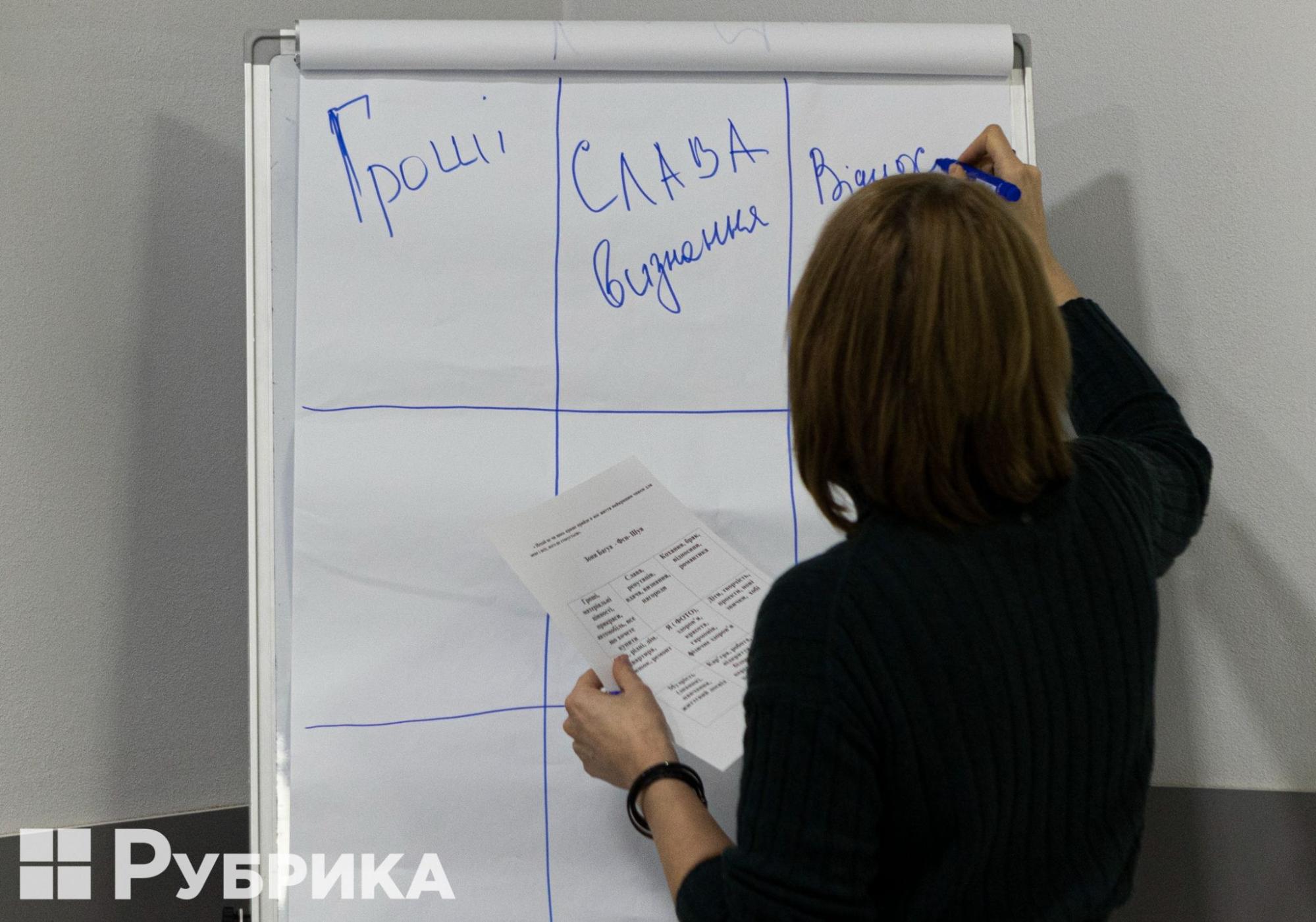

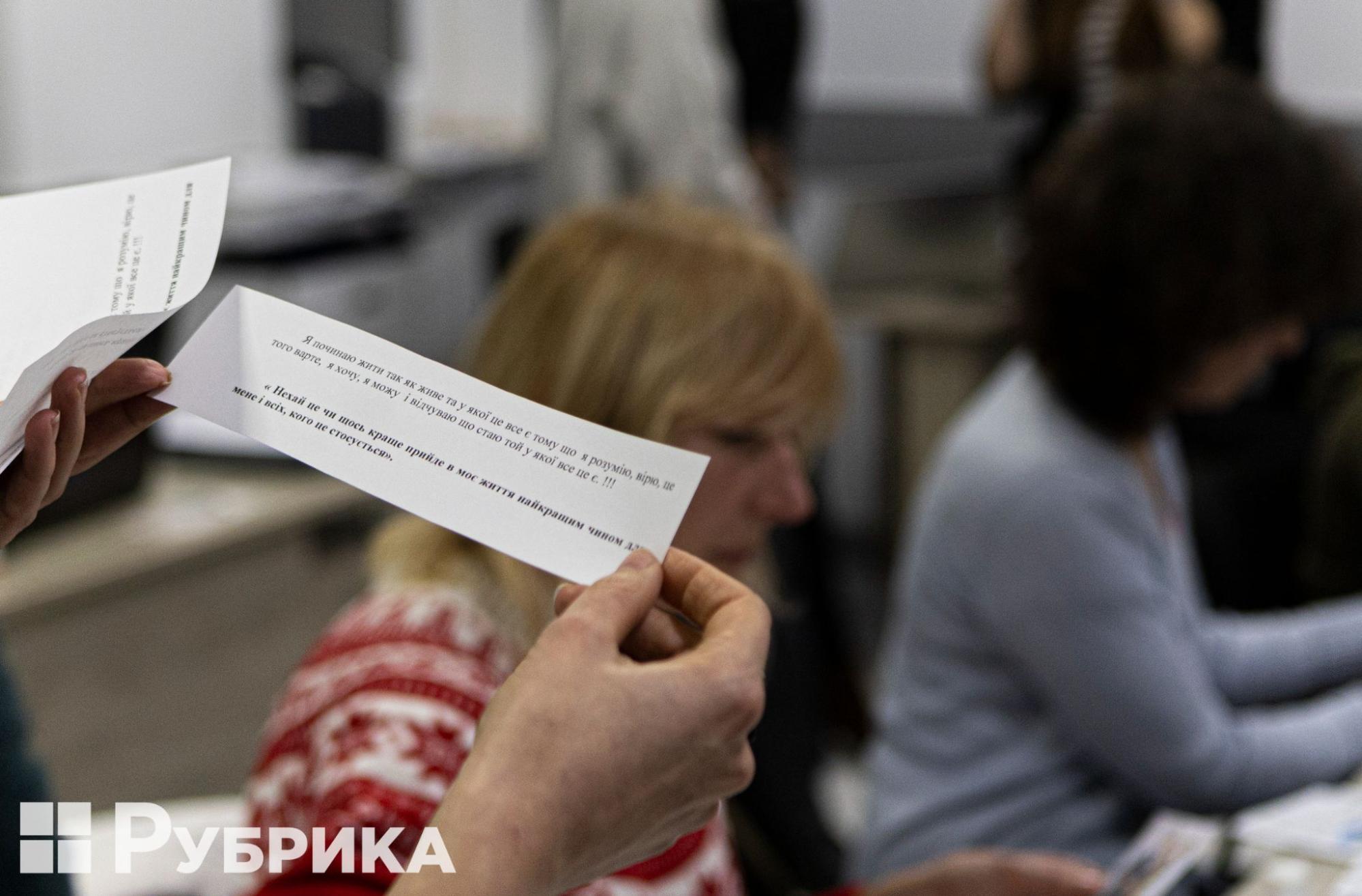

Psychologist Tetyana Voloshyna writes words on the board. This is what visitors to the center will be working on today — a wish map for 2024. People who have suffered trauma often do not have the inner resources to dream; it is difficult for them to plan because negative experiences have taught them that you should not set goals because it will be easier to accept if things go wrong.

Tetyana Voloshyna, psychologist, psychotherapist, art therapist.

Voloshyna's goal is to give people a chance for inner recovery, teach them to live anew, set goals, and not be afraid to see themselves happy in their future.

"I like that people here are very open and interested in getting out of their situation. There is such a beautiful expression among psychologists: look for your people. Perhaps, here I found mine. They want changes and go for these changes, and I ignite them," she says. The psychologist has been volunteering for half a year; the center gave her self-development, improvement, and people: "I really belong here."

Participants write their wishes for 2024.

Psychological help from Zmist works not only in Poltava — the center organizes mobile trips to the Poltava region, where it cooperates with five communities. They go on trips with child and adult psychologists, whom residents willingly visit. The requests are different: anxiety, sadness for relatives at the front, and personal experiences. The team's wish map for 2024 is to cooperate with all communities of Poltava.

After forming plans and desires, the psychologist offers to fix them with visual images — this is where clippings from magazines and scissors will be needed.

Nadiia and her dog after creating a wish card.

The youngest participant works the most actively — this is Nadiia's dog. She has a very responsible role in encouraging women and not letting anyone feel sad.

Nadiia herself is from Poltava but often attends training sessions. One day, a neighbor showed her an advertisement that the Adaptation Center was looking for a yoga teacher, which was Nadiia's favorite activity. In 2022, she even visited India, where she studied meditation. Since then, Nadiia has held many master classes and yoga classes. She says that she is pleased when she sees how engaging the participants are and how they try, listen, and ask many questions.

The participants are all at work: they carefully glue illustrations and tell their neighbors what they want in the future. Olena's son dreams of a dog, so the dog's photo is the main focus of the card.

Olena herself shares: "I really want peace, and for myself — a family vacation. I'm taking driving courses now, so maybe a car. Here, nothing global — only happiness, peace and tranquility."

Such warm meetings with a psychologist are held at the center every week and allow you to share your experiences, find a new circle of acquaintances, and learn more about emotions and self-help methods. In addition, there are trainings on medical and psychological topics and English language courses, where a group with an intermediate language proficiency is currently studying. They even held a master class on making smoothies!

There is also a School of Health, where doctors come and talk on a certain topic. There was a case when IDPs could come and test blood for sugar levels free of charge. The girl came to support her mother and donated blood to the company. It turned out that her sugar level was almost four times higher. She consulted with doctors for a long time, and they advised whom to contact. Not everyone has the means to take tests, and not everyone knows where to go. "Here, they can hear about diabetes, learn about the first signs of oncological diseases, and other health issues," shares the center's HR manager.

The previously mentioned cultural initiative also works regularly — the team shows IDPs Poltava, organizes museum visits and visits to the Philharmonic and theaters and holds tea parties. Molka adds: "This brings people together and helps to find friends in Poltava. People often come to me for an interview or career counseling and share that they don't even have anyone to leave a child with. We aim for people to find friends and acquaintances."

Does it really work?

Together we are strong

The integration of IDPs is a question of whether we as a state can involve the whole society in reconstructing Ukraine. Do not distance yourself from their problems, but find a truly useful and effective solution. The community will only benefit if it integrates the newcomers into its economy and provides a comfortable stay where residents can fully realize their ambitions for the benefit of the city or village.

Although adaptation centers will not be able to solve the entire problem at once, they have a point-by-point effect: in their place, in the community, and the worldview of the participants. They are about the life stories of individual people, which together become the great story of the entire country.

Such initiatives provide an opportunity to restore life, which is difficult to start from scratch — without finances, support from the side, and support in an unfamiliar place, with a lack of understanding of what to do next.

"I remember my first working day: a woman comes with tears in her eyes, asking if we have anything because they just left from a dangerous region. You can no longer act as an employee — you are already a person interacting with a person. You want to help but can't do it right now because there is nothing. You can write down her name for the future when there will be new humanitarian aid. You understand that not everything is in your power; you can't be a superhero for everyone, but you want to help," says Anastasiia Myshun, manager of the economic department.

From left to right: Svitlana Boychuk, Anastasiia Myshun, Ilona Oryshchenko.

In this way of helping IDPs, the Zmist team made projects by trial and error, focused on feedback, and used all possible communication channels. Kutsenko insists: "We are all here for the result; the process can be anything: stupid, exhausting, crooked, and incomprehensible because we have never done this. But every achieved goal is a victory for us personally."

The main challenges are in attracting funding and specialists. Interaction with specialists is easy: everything happens on barter cooperation, where for a lecture or training, the organization undertakes to tell about the speaker to reinforce the expertise of the guest with an announcement. Financing is a hot issue. Not all non-governmental organizations, volunteer headquarters, and charitable foundations invest a significant part of their time and resources in the search for financial donors, grants, and partners. "Starting this year, we decided to increase the chances of receiving funding. That's why the heads of all departments in Zmist participate in fundraising. That is, one way or another, in pieces or in full, we write applications for grants because we understand that this is necessary for the Center for Adaptation, rent, wages, etc.," adds Kutsenko.

Merch of the organization.

The head of the NGO says that every day, the team comes up with new solutions if only to attract as many people as possible to support the center and IDPs — they hold auctions, where lots are drawn for the largest donation. The lots vary from axes to gyroscooters. Behind every funny lot is a sad truth — volunteers must repeatedly explain how important systemic charitable support from civilians is.

One of the lots.

Sweets that were collected last year.

While we are talking, a woman walks into the bookstore with a bag of goodies in her hands. She brought them to participate in another Zmist initiative — sweets for the Armed Forces. She is the mother of three lieutenants, and all her beloved men are now at the front. A woman brings candies and bars to Zmist so boys and girls like her family can have something sweet on a cold night.

A conversation begins between the women, and Kutsenko tells us, "You understand that you did not live this day in vain. You made some contribution to Ukraine's victory. You contributed to helping a person. This is what drives me forward."