Mikael Colville-Andersen explains that the concept of therapeutic gardens has a rich history, dating back thousands of years. He cites the Romans, who used gardens not only as sources of food but also as places for therapy. He also references the Japanese practice of "forest bathing," which encourages people to immerse themselves in nature as a form of healing.

He emphasizes that the therapeutic benefits of nature are intuitive to people, but scientific research supports this intuition. Studies have shown that being in nature can significantly reduce stress. That's why, about 15 years ago, researchers from Denmark and Sweden began exploring how nature can aid in the treatment of psychological issues.

Their findings revealed that therapeutic gardens can not only alleviate stress but also help treat psychological trauma and PTSD, provided the garden's design incorporates principles of human behavior.

"This field of study has become so established that every town in Denmark now has therapeutic gardens. They are utilized not only by citizens dealing with everyday stress but also by veterans from various conflicts," says Colville-Andersen.

Danish urban planner Mikael Colville-Andersen. Phoro: Facebook/ Mikael Colville-Andersen

What is the problem?

After living in Ukraine for two years, Colville-Andersen noticed the mental health challenges faced by Ukrainians. He realized that therapeutic gardens could be beneficial, yet none were being developed in Ukrainian cities. He couldn't understand why.

The answer came during a conversation with his German friend. While walking in Podil, one of the oldest neighborhoods of Kyiv, they discussed therapeutic gardens, but she had never heard of them. This made him realize that the concept had never spread beyond Denmark and Sweden, which explained why it was unknown in Ukraine as well.

"Then I thought, if anyone needs this, it's Ukrainians—not just veterans, but everyone in society. We all face different levels of stress and trauma, so I decided to try implementing a pilot project here in Kyiv, hoping to inspire more such projects across Ukraine," says Colville-Andersen.

What is the solution?

The urbanist explains that everyone he spoke with was captivated by the idea of creating a therapeutic garden in Kyiv. As a result, he quickly found people willing to finance the project, but the process was delayed by bureaucracy.

"At some point, I thought, 'This is a garden, and it's spring—the time to start planting.' I didn't have any money yet, but I just said, 'Hell, let's do it,'" recalls Colville-Andersen.

He decided to establish the garden near the Psychiatric Hospital named after Pavlov in an abandoned area. Obtaining a land use permit was relatively easy because everyone he spoke with understood the garden's importance.

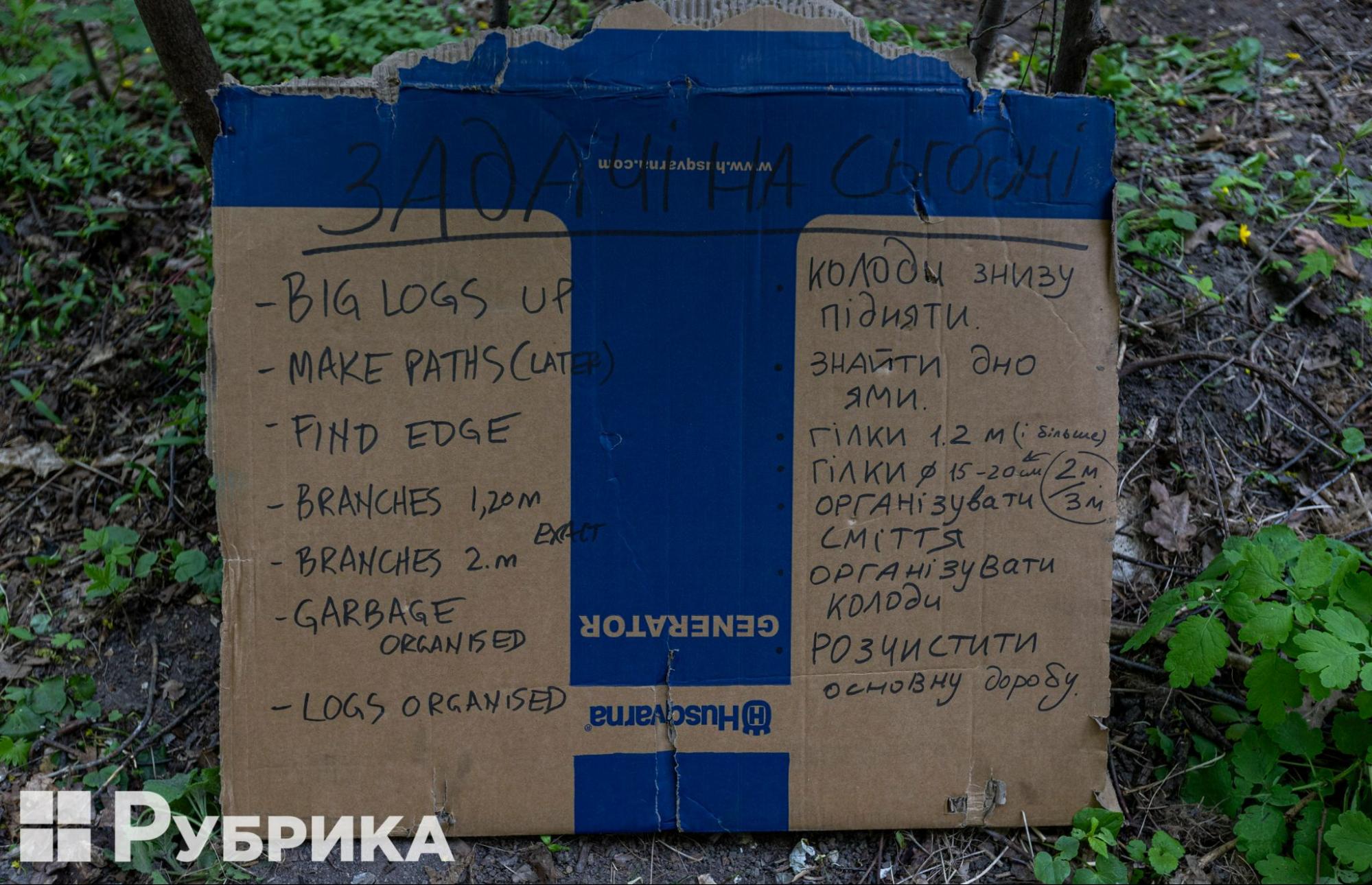

Next, he started a crowdfunding campaign to collect funds for the necessary supplies to start the project. Once he had raised enough money, he organized a community clean-up, or "toloka," to clear the area of deadwood, which was later reused, as well as a significant amount of garbage.

"I expected 50 people to show up on the first Saturday, but 500 came over the weekend. This shows how intuitively Ukrainians understand the importance of the garden. It was crazy. Every weekend for the next 11 weeks, there may not have been as many people, but there were always enough to get the job done," says Colville-Andersen.

The urbanist emphasizes that the project's success was due to "the combination of volunteer spirit and the willingness of sponsors to support the project." The Danish Cultural Institute and the House of Europe provided the largest financial support, while Jysk and the Rotary Club contributed over $3600 to cover the cost of wood. Additionally, Dnipro M and Husqvarna supplied the tools and generators needed for the work.

In just eleven weeks, a core team of about 15 dedicated volunteers emerged, giving up their weekends to advance the project. Their efforts paid off, and the ceremonial opening of the therapeutic garden took place on June 28.

How does it work?

Colville-Andersen explains that when creating therapeutic gardens, it's essential to consider theories about human behavior. The theory underlying the Kyiv garden is called the "prospect-refuge theory," which explains how to design environments that feel psychologically safe.

The idea is that for millions of years, humans have needed either refuge—a place to protect themselves from potential threats—or prospect—the ability to scan their surroundings for danger. This need persists even today.

"Even in everyday life, it's important for people to have something solid behind them. For example, in a café, if I sit with my back to the wall and you sit with your back to the open space, I feel safer, while you may feel less protected," says the urbanist.

To address this, he designed special three-sided gazebos. One wall is made of solid wooden logs or beams, creating a strong sense of security. The two adjacent walls resemble a fence that partially encloses the person, providing both protection and the ability to observe their surroundings. The fourth side is open, allowing for easy scanning of the area. This design gives a person a sense of security while also offering the opportunity to look around, enabling them to feel safe and relaxed in the space.

Another important element of landscape design is the concept of perspective. It's not necessary to see literally 20 kilometers ahead, but there should be a sense of being able to view something in the distance, whether it's a lake, a river, or just an open space.

"We designed our garden on a hill to provide this distant view, creating a bubble of nature that envelops people," comments the urbanist.

View of the therapeutic garden from the hill.

Another theory used in this garden is called the "attention restoration theory." Living in the city, people are bombarded with information every second. Our brains constantly have to filter this influx because they can't handle such a large volume, which can lead to feelings of depression.

In contrast, when you sit in a garden among trees, the number of stimuli is significantly reduced. You're left with just the sounds of birds, the rustle of leaves, the smells of plants, and the overall feeling of being in nature. This reduces the brain's workload and allows it to rest.

"It's a forest, so there are already trees here, but we've added a variety of plants to provide a sensory experience throughout the year—spring, summer, fall, and winter. We mixed them with pines, which have a soothing smell. We also planted climbing plants whose leaves remain in winter. This helps protect the garden from wind and noise all year round," says Colville-Andersen.

The therapeutic garden is also divided into three levels, depending on the severity of mental issues. The first level is for those who have suffered the most—people who can barely talk or leave the house. These individuals might struggle with paranoia or suicidal tendencies. According to the urbanist, such gardens may only offer limited help to them. For these individuals, there are gazebos with a single chair, providing a space to be alone. It's an opportunity to sit quietly, begin working on their problems, and let nature offer some assistance.

The second level also has gazebos, but with benches where people can sit together. Unlike the first level, these areas encourage those who are starting to talk and recover to sit with family, caregivers, or friends.

The third level of the garden is a communal area with a fireplace and a circular space for group activities. Here, people can chop firewood and engage in garden therapy. There are special boxes where they can grow their own plants, and a physical activity area where they can balance on a track.

"When you're depressed, whether it's because of a breakup or PTSD, it feels like everything is happening in your head. You're sad, lying on the couch, but then your brain starts to reconnect with your body. You realize, 'Oh, I have arms and legs. I want to do something.' Garden therapy helps with this—cleaning, gardening, chopping firewood," says the urbanist.

Colville-Andersen notes that the garden has already attracted a number of visitors, including patients from a nearby hospital. Many doctors from the hospital now bring their patients to the garden, and some even helped build it. The urbanist has also spoken with veterans who visited the park, and they described the project as "amazing and useful."

The town planner is now looking to secure funding to hire two people to provide information and guidance in the garden. Once the project is fully completed, he does not plan to develop new gardens.

"Personally, I don't want to build more gardens. I am an urban planner, not a landscape architect, although I became one for this project. It was an incredible experience, but now I have other projects," says the urbanist.

Instead, Colville-Andersen aims to focus on organizing workshops for mental health professionals and landscape architects. He hopes that his experience will be useful and inspire the creation of therapeutic gardens in other cities across Ukraine.

Several Ukrainian cities have already shown interest in the project, including Rivne, Cherkasy, and Lviv. There is also interest in creating a therapeutic garden for Ukrainians and locals in Bratislava, the capital of Slovakia.

As Colville-Andersen completes the therapeutic garden in Podil, he is transitioning to other projects. He describes the work as challenging, particularly in terms of logistics and organizing groups. Although he is not eager to go through the process again, he is happy to offer advice to those looking to build their own gardens.

"I have always been a city person. I need to sit in a café and observe people's behavior. But this project was a bit of a joke on myself: I suffer from severe anxiety, so I built a garden as my own therapy and then shared it with the people of Ukraine. Being in the forest every day, designing, and working with people was therapeutic for me. But now, I need to return to city life," says Colville-Andersen.