What is the problem?

In the year and seven months since the start of the full-scale invasion, Russia has committed 536 crimes against journalists and the media in Ukraine. These are the data from the monitoring of Russian crimes against journalists and media carried out by the Institute of Mass Information (IMI). In particular, according to IMI, 67 journalists have been killed since the beginning of Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, 10 of them while performing their professional duties.

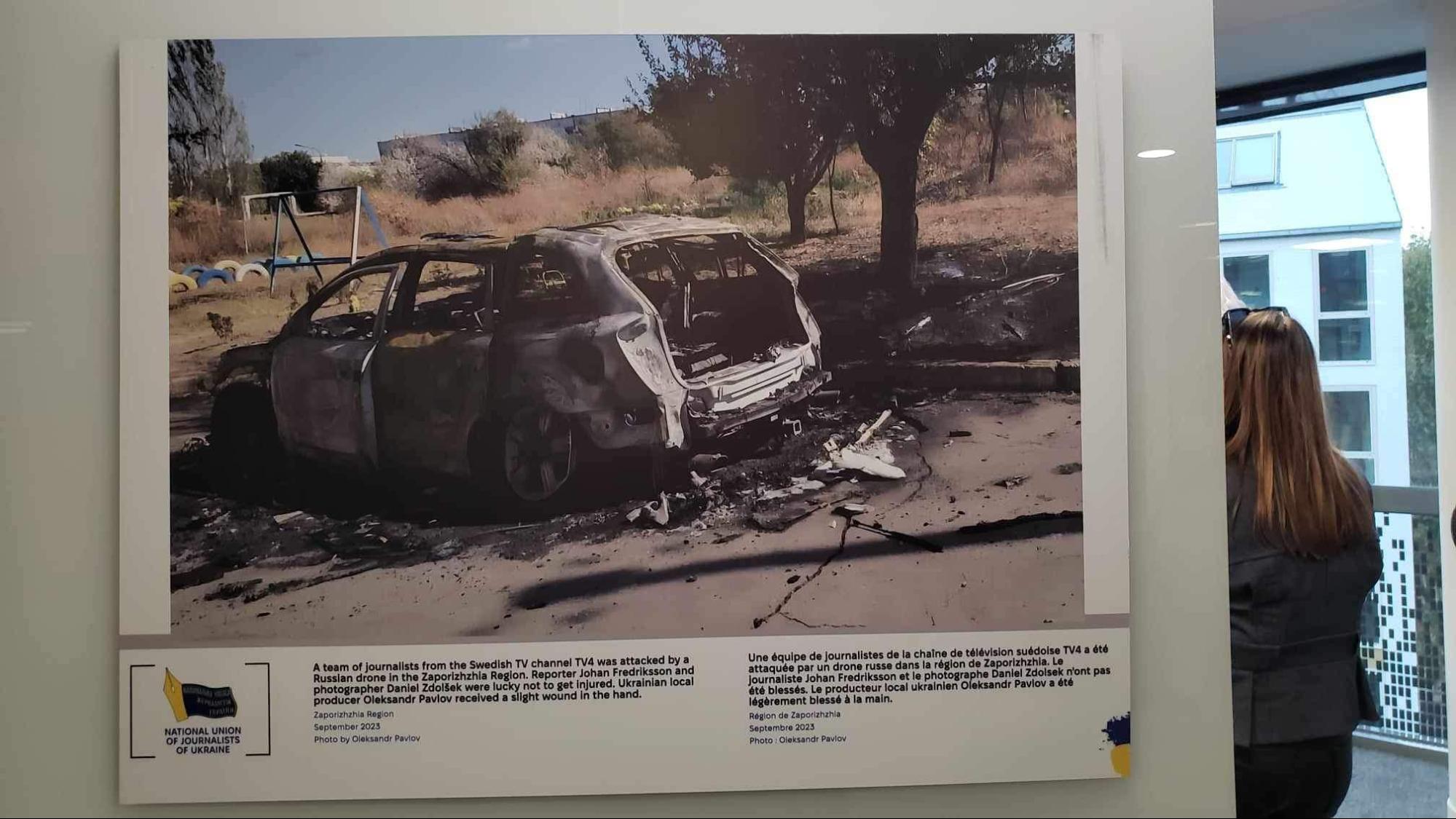

Among those, the enemies attacked in September of this year is the film crew of the Swedish television channel TV4: reporter Johan Fredriksson, photographer Daniel Zdolsek, and their fixer, Ukrainian journalist Oleksandr Pavlov.

An attack on journalists by a Russian drone

It happened in the Zaporizhzhia region. Russians attacked journalists on September 19 with a drone in Stepnohirsk, which is near the front line.

All film crew members were wearing civilian bulletproof vests and helmets with the inscription "Press." As soon as they started working in the area most affected by Russian shelling, one of the two policemen accompanying the group warned of the approach of a Russian drone.

The Swedish media members got out of the car at that moment and were not injured, but, unfortunately, Pavlov was wounded, as well as two Ukrainian police officers who accompanied the TV4 team to the scene. Fortunately, the injuries were minor.

The police officers who accompanied the film crew and Oleksandr Pavlov were injured. Photo from the archive of Oleksandr Pavlov

"We're filming, and I see a drone flying at me. It was already so close that I even managed to make out its details. In a fraction of a second, I jumped to the side and fell to the ground, and the drone operator sharply turned it in the direction of our car, which burned immediately after being hit," recalls the journalist Pavlov.

As a result of the attack, the car was destroyed, as well as filming equipment, laptops, telephones, and other personal belongings of media workers.

A photo of a car burned by a Russian drone of a team of Swedish media at an exhibition in Paris organized by the International Federation of Journalists and NUJU. Photo from the archive of Oleksandr Pavlov

What is the solution?

Colleagues from foreign and Ukrainian media who lent equipment helped the Swedish journalists to complete the story: Al Jazeera, the French channel LCI, and Channel 5 correspondent Denys Rozenkov.

Ukrainian colleagues and people who care also supported Pavlov with funds to restore equipment for work. The National Union of Journalists of Ukraine handed over a laptop from German benefactors and businessman Yevhen Chernyak — 20 bulletproof vests of protection class 4+ not only for Pavlov but also for other journalists, fixers, and drivers of media groups covering events in the war zone.

"Getting hit by a Russian drone is not heroism. Heroism is working and giving material from a place where such a drone, projectile, rocket, and other deadly thing can fly. Many of my dear and respected colleagues do so. Both Ukrainian and foreign," says Pavlov.

Oleksandr Pavlov with Zaporizhzhia police officers. Photo from the archive of Oleksandr Pavlov

In his opinion, the current task of Ukrainian fixers is to maintain and not let the world media's interest in the events of the Russian-Ukrainian war fade away.

How does it work?

Pavlov is an experienced journalist from Zaporizhzhia who, before the full-scale war, headed a media agency and implemented major international projects.

Oleksandr Pavlov at the meeting of foreign ministers of EU countries in Kyiv. Photo from the archive of Oleksandr Pavlov

"On February 24, 2022, I realized that none of my previous projects will have a demand in the near future. Therefore, on February 25, I got into the car and drove to Kyiv, from where everyone was urgently leaving," recalls Pavlov. Since the beginning of the full-scale invasion, he has continued to work as a journalist, including covering events in Ukraine for the Finnish media outlet Iltalehti, working with French media, and working on other projects.

After a week in Kyiv, the legendary Spanish journalist Javier Espinosa unexpectedly offered to cooperate with Pavlov. Before that, he was in 17 hot spots. In 2014, he spent half a year in an ISIS prison in Syria.

Javier Espinosa offered cooperation precisely as a fixer because Pavlov is fluent in English and French. As a journalist, former press secretary, and adviser to the heads of the Zaporizhzhia Regional State Administration, he knows Ukrainian realities well.

During this time, Pavlov traveled all over Ukraine with journalists from various world media and, as he admits, even discovered it for himself in a new way.

Oleksandr Pavlov while working in Kharkiv region in 2022. Photo from the archive of Oleksandr Pavlov

At the same time, he developed his own rules that those who work as a fixer should follow. By the way, Pavlov does not like the word "fixer," and the term "local producer" also seems inaccurate. For him, it is rather co-authorship.

He believes that the job of a fixer is to introduce a foreign journalist into Ukrainian realities, to unobtrusively explain the context of how Ukraine has been living for the past 30 years and what is happening right now.

Narrative that will help to work in the frontline zone

The first point is that war should be treated as war. This is definitely not an adventure. This is blood, tears, cruelty. It is impossible to get used to it. But you have to try to push emotions into the background during work.

"Learn to be a part of this reality. Do what you have to do and let it be what it is. Military journalism is work. Do it professionally," advises Pavlov.

Therefore, the second point is that written rules cannot be neglected. A helmet and a bulletproof vest are mandatory, even though they are heavy and uncomfortable.

One of the trips with foreign journalists in the summer of 2023. Photo from the archive of Oleksandr Pavlov

The case in Stepnohirsk is not the first risk situation for the fixer, but it was the first serious one. Before that, together with Sky News journalists, he came under Russian artillery fire in the Huliaipole district in the Zaporizhzhia region, and even earlier, together with France 5 media representatives, they came under enemy mortar fire near Bakhmut. Every time was scary.

If there is a ban on access to certain places, you must obey these bans.

"A fixer is a dangerous profession. If you can reduce the risks to life, reduce them. Your weapon is not a machine gun. But it is no less important," says Pavlov.

A car of media workers destroyed by a Russian drone. Photo from the archive of Oleksandr Pavlov

The third point is to be polite. Polite without flattery. Keep calm and composure, and smile.

"Be friendly. Sometimes your smile is what soldiers on the front lines or people waiting in line for evacuation are waiting for," said the fixer, who, during this work, got to know Donbas so much that he could drive through these areas with his eyes closed. The Odesa, Kherson, Mykolaiv, Zaporizhzhia, Sumy, and Kharkiv regions, unoccupied parts of Luhansk and Donetsk regions, and even rear Lviv — Pavlov visited all these areas from the beginning of the full-scale war.

The fourth rule is to help with what you can.

"Help the military to repair a car stuck on the side of the road. Buy food and water for those fleeing war. Share the necessary contacts with colleagues. It's not difficult. But they will definitely come back to you," the journalist-fixer is convinced.

He recalls a case when he traveled with Swiss journalists to Orihiv in the Zaporizhzhia region, where they met soldiers in a field near the liberated villages whose car radiator coolant boiled. They needed water to get to the nearest repair point. The journalists poured water from all their bottles and helped the soldiers.

Fifth — "Your work is very important. The world needs to know the truth. Remember your responsibility for every word."

According to Pavlov, the fixer, for all their patriotism, should not interfere in the work of a journalist. It is about the moments of the work of a foreign media representative when they record an interview or a report.

"Patriotism is not about imposing something on a media representative to rudely influence their work but to let the foreign audience feel what is happening. To bring to the place, to arrange meetings, to give an opportunity to talk, adequately, with preservation of all meanings, to translate what was said by the conversation participants," Pavlov explains his opinion.

After that, when the journalist has already processed the material, in a private conversation, it is possible and sometimes necessary to express your opinion so that the journalist does not inadvertently harm the Ukrainian military with their material. Recently, this happened to Pavlov with a large European media outlet when it made material about the work of the Ukrainian defense enterprise during the war. Then, it was possible to convince them that certain information should not be presented in such detail.

The sixth point is to build connections. Communicate, even if it seems troublesome and useless at first.

"For the fourth time, I came to Kharkiv, for example, as a well-known city," says Pavlov, who visited the Northern Saltivka district more than a dozen times with various media representatives.

The last, seventh point is to think about the future. It is beautiful and amazing, Pavlov is convinced. During his work as a fixer, he saw the lovely people of Ukraine resisting evil.

"These are largely dramatic stories of the human spirit, mutual help, and, at the same time, terrible betrayal, which cannot even be described in words," Pavlov shared with Rubryka. "War creates both stories. For me, there were many discoveries, how people change, and more often — for the better."