One Ukrainian company, Tesla Energo LLC, which builds and supports the maintenance of industrial solar power plants, has recently taken up farming. It used the land near its solar power station in the Zhytomyr region to create a small farm. In the summer, their farm has sheep roaming freely between the solar panels and rows of blueberries flourishing nearby. The farm spends little to no money on mowing.

Agrivoltaics, which combines energy production and farming, isn't just a theory — the Tesla Energo farm is proof it can work in Ukraine. For now, it's the only case like it in the country, but with the right approach, it could be replicated nationwide.

While agrivoltaics is gaining momentum in Europe, Rubryka looks at how Ukrainian farmers can jump on the bandwagon and adopt this clever farming model in Ukraine.

Hanska Solar Power Station, Zhytomyr region. Photo: Tesla Agro

What's the problem?

Agriculture is one of the pillars of Ukraine's economy, even as the war has caused billions in losses to the sector. Farmers have no choice but to adapt as new challenges demand new solutions.

Energy shortages are becoming a problem for farmers. Ukraine's energy system, devastated by Russian attacks, lost its resilience in 2023 and can no longer handle peak demand. With summers getting hotter every year, the need for electricity is only growing, as attested by rolling outages Ukraine had to introduce during the heatwaves of July and August 2024.

Ukrainian farmers can't help but be affected by outages. In summer, dairy farmers need to keep refrigerators running to preserve milk. Crop growers rely on electricity to power irrigation systems. Poultry farms need the power to maintain incubator temperatures, and grain elevators need it to dry harvested grain — otherwise, entire yields can be lost to rot and pests.

With blackouts threatening the backbone of Ukraine's economy, the need for quick, effective, and affordable solutions has never been greater. Agrivoltaics, an approach that allows land to be used for both farming and solar energy production, could be one of them. Farmers can grow crops or graze animals and produce renewable energy, minimizing land loss to no more than 15%. Green energy can help farmers adapt to climate change and be used on-site or sold for extra income. A smarter, more sustainable way to farm? It just might be.

What's the solution?

Tesla Energo LLC built the Hanska Solar Power Station near Berdychiv in 2019 as a commercial project to sell electricity to Ukraine's power grid. While solar power projects were already common in the south of Ukraine, the Hanska station stood out.

One of the challenges with solar stations is dealing with the grass growing underneath and between the panels. If the plants touch the panels, it creates a fire risk. Raising the panels isn't an option as it is costly and inefficient. On top of that, European ESG investment policies prohibit using chemicals on-site for green energy production, meaning the company can't just spray the grass to kill it. So, the grass has to be constantly mowed, consuming extra resources.

Tesla Energo found the solution for the Hanska station. Olha Hramotenko, the project's founder, decided to borrow a concept from similar projects in Denmark and use animals to take care of the grass. At first, the company considered goats but eventually settled on sheep, calm enough not to jump on the panels and small enough to easily pass underneath. They were the perfect natural lawnmowers, with skills that would put even the most manicured English lawns to shame. So, 60 sheep were brought in.

Solar panels didn't cover all the land because the terrain didn't allow it, so the company planted around 1.5 hectares of blueberries and strawberries and installed an automatic irrigation system powered by the station's solar energy.

Hanska Solar Power Station, Zhytomyr region. Photo: Tesla Agro

Since then, the sustainable project has successfully combined three functions — sheep farming, berry cultivation, and solar energy production. Even better, the cost of breeding and maintaining the sheep is covered by selling new livestock. For instance, the station had 80 sheep just two years ago, but the number grew to 250 last year. The company sold some of them, leaving 125 sheep and one ram. Tesla Energo Service, a subsidiary of Tesla Energo, handles the maintenance of the station. According to Hennadii Nesterchuk, the company's director, the sheep do about 80% of the mowing, while the remaining 20% still needs a human's hand.

Hanska Solar Power Station, Zhytomyr region. Photo: Tesla Agro

Yurii Sarnavskyi, the project manager for Tesla Agro, says this model is proving to be a win. Yet, the Hanska station remains the only solar station in Ukraine that has fully adopted agrivoltaics. Sarnavskyi notes that the company had clients interested in creating similar projects, but the full-scale war put a stop to that. So, the question remains — why haven't more Ukrainian farmers adopted this sustainable model?

How does agrivoltaics work?

Let's go back to the basics. Agrivoltaics, in its most widely accepted definition, is a dual land-use technology that:

- Integrates renewable energy sources with agricultural systems and technologies,

- Doesn't reduce agricultural land suitability by more than 15%,

- Improves adaptation to climate change, and

- Allows for the efficient use of land resources to grow crops and improve animal grazing conditions while generating electricity for personal agricultural production or sale.

The Hanska solar power station is an excellent example of applying agrivoltaics principles. However, it's not a traditional agrivoltaics model. There are many more variations of this technology.

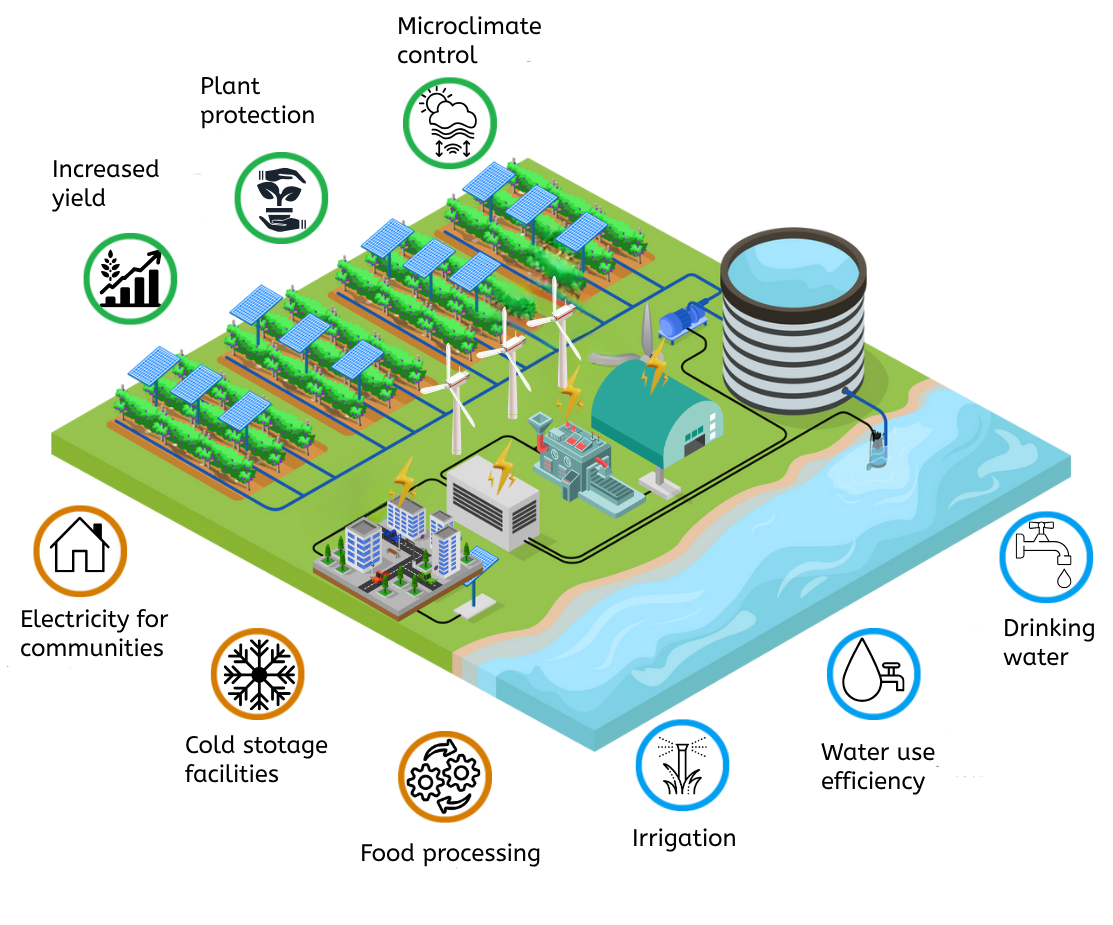

Here's a look at the traditional agrivoltaics setup. Infographic: Association of Agrivoltaics Ukraine

Vladyslav Sokolovskyi, the chair of the Solar Energy Association of Ukraine, classifies agrivoltaics into "traditional" and "non-traditional." With traditional agrivoltaics, solar panels are installed at a certain angle, 2–5 meters above the field where crops are grown. Some panels are equipped with mechanisms that adjust their tilt based on the sun's position or the needs of the crops. The land beneath the panels is suitable for farming, grazing, or more.

The electricity produced can be used locally — to power irrigation pumps and cooling systems at the growing site, for primary food processing, for community needs, or to be sold to the grid.

Traditional agrivoltaics offers many benefits, including:

- Increased revenue from selling electricity,

- The ability to provide autonomous water supply from wells,

- Protection of plants from extreme weather, like intense heat, heavy rain, and hail,

- Partial shading from the panels can reduce water evaporation from the soil.

These advantages allow farmers to cultivate more crops and develop their businesses. Renewable energy use could also make Ukraine more energy independent, make land use more efficient, and reduce carbon emissions.

However, agrivoltaics also has other forms that seem unconventional but still viable, like installing solar panels on unused land or rooftops.

Why hasn't traditional agrivoltaics taken off in Ukraine?

The major obstacle to agrivoltaics in Ukraine is simple: the law. Right now, it's illegal to install power-generating facilities on agricultural land. The Hanska solar power station bypassed this restriction only because its territory is officially classified as land for "industrial, transport, communications, energy, defense, and other uses." It started as a solar station, which later incorporated farming.

For most Ukrainian farmers, whose land is strictly categorized as "agricultural," this legal barrier makes traditional agrivoltaics impossible. One exception is farmers growing crops or raising livestock on private household plots. In those cases, the restrictions don't apply, making small-scale agrivoltaics an option.

However, even if the law changes tomorrow, another problem remains, says Sokolovskyi: many farmers don't see the economic benefit.

"Farmers have no desire to invest in solar stations, especially during the war, when they already have more than enough to worry about," says Vladyslav Sokolovskyi. "The only real, economically viable option is to find a partner willing to build a solar station on their land so they can both profit. But even then, it's not that simple."

- The first challenge is technical. Solar panels in fields must be installed at a certain height, which drives up costs. Many businesses investing in solar energy prefer easier options — like empty land or warehouse rooftops.

- The second challenge is trust. Farmers aren't confident in Ukraine's Guaranteed Green Energy Buyer, the state-owned entity that's supposed to represent the interests of both citizens and the government in the electricity market and purchase renewable energy to support the producers. In theory, the "green tariff" ensures payments to renewable energy producers, but in reality, the government has fallen behind on its obligations and owes large sums to green energy companies.

- The third challenge is infrastructure. Even if farmers build solar stations, they often lack nearby substations or power lines to feed the electricity into the grid. The investment doesn't make sense without a way to sell the power.

How can farmers use solar energy?

Farmers in Ukraine have two main ways to harness solar power. The first is for their energy needs — powering their homes, equipment, or storage facilities. The second is selling electricity, though this comes with the same roadblocks that hinder traditional agrivoltaics: unreliable payments under the "green tariff" and a lack of infrastructure to connect to the grid.

The first option is desirable for farmers in remote areas, far from high-capacity substations. In such cases, installing a solar power system with batteries is often cheaper than running new power lines. More than that, solar panels give farmers energy independence. Their work no longer relies on the national grid — a crucial advantage during blackouts and rolling outages.

Some of Ukraine's most prominent agricultural companies, like MHP, already use this approach. MHP is currently building the country's largest battery storage system for solar energy. Smaller farms also install solar panels for self-sufficiency, a trend that's becoming common in rural areas.

"For example, a farmer might put up solar panels on the roof of their house to power their household or keep their refrigerators running if they produce dairy. It's a great setup because refrigeration is most needed in summer when solar panels generate the most energy," says Sokolovskyi.

So, what's the big picture? Traditional agrivoltaics hasn't taken off in Ukraine, mainly due to high costs, a lack of willing investors, and, most importantly, laws that could regulate dual land use. However, farmers and agricultural businesses are still turning to solar energy to meet their needs. In a way, that's agrivoltaics too.

According to Yurii Sarnavskyi, one agricultural company has even approached Tesla Energo LLC to develop a traditional agrivoltaics project.

"For now, it's just in the planning stage," says Yurii. "This is a company we worked with when developing our project — they shared their agricultural expertise with us. Now, they want to follow our example and build an agrivoltaics system of their own."

How is it working elsewhere?

Czech journalist Karolína Chlumecká looked into agrivoltaics in her country for Ekonews. She reported that the technology is helping farmers cut costs, an increasingly urgent issue for the Czech Republic as fertilizer and electricity prices continue to climb.

According to the Czech Statistical Office, 4% of the country's farmers already rely on renewable energy sources like solar panels and biogas. Agrivoltaic panels can generate up to 0.9 megawatts of power per hectare, producing as much as 855 megawatt-hours of electricity annually, which can power about 250 average homes for a year. Unlike traditional solar farms, however, agrivoltaic panels allow sunlight to reach the crops below, slightly reducing their efficiency.

Some Czech agricultural experts believe agrivoltaics could affect yields, but not all crops suit this approach. Martin Sedlák, Program Director of the Modern Energy Union, and Martin Ludvík, head of the Czech Fruit Growers Union, echoed a point made earlier in this article by Vladyslav Sokolovskyi, Chairman of Ukraine's Solar Energy Association. For fruit farms looking to cover their energy needs, installing solar panels on warehouse and facility rooftops should be the first step.

Even so, Czech farmers are already experimenting with traditional agrivoltaics, testing various panel designs. In orchards, they mount them at a height of four meters; for berry fields, the standard is 2.5 meters. However, one major challenge remains: the cost. Because of the complex structures and limited-scale production, the payback period for installations can extend as long as 20 years.

Legislation plays a key role in shaping the future of agrivoltaics. In 2024, the Czech government passed amendments allowing solar panels to be installed over vineyards, orchards, hop fields, and other agricultural land without stripping the land of its agricultural status. From 2026, these projects will also qualify for financial support from the government.

What should Ukraine keep in mind?

"Since the 1950s, European electricity demand has risen by 20–40%. That means we need new power generation sources," says Viktor Ivkin, head of the Association of Agrivoltaics Ukraine. "If even 1% of farmland were dedicated solely to solar energy production, we'd logically see a 1% drop in food output. That, in turn, would increase the number of people going hungry — mainly in African countries — by several percent. And that means a global food crisis. So, we have no choice but to find a way to use agricultural land for both farming and energy generation."

Ukraine's Association of Agrivoltaics has created a detailed roadmap, which includes everything from developing university programs on agrivoltaics to launching research hubs and innovation accelerators for startups in the field. The nonprofit has already signed agreements with Ukrainian universities to help train future specialists. In April 2025, a major intersectoral conference will bring together Ukraine's higher education institutions to discuss the technical aspects of solar panel installation and ways to adapt crops — through genetic modifications — to grow effectively under agrivoltaic conditions.

"Right now, Ukraine is just stepping into the world of agrivoltaics. It's still a Blue Ocean," says Viktor.

For agrivoltaics to take off, Ukraine first needs to change its laws to allow power generation facilities on agricultural land.

Beyond that, the country needs to consider another critical issue: solar panel recycling. As agrivoltaics expands in Ukraine, so will the need for proper disposal and reuse of panels.

Polina Kolodiazhka, co-leader of Greenpeace Ukraine, told Rubryka that her organization has studied solar panel recycling worldwide. Even though solar panels contain valuable materials that can be reused, the field is still severely underdeveloped.

"Solar panels hold materials that are not just valuable but fully recyclable — glass, silver, copper, aluminum, and silicon," says Polina. "That means they can be repurposed, and companies are interested in doing that. Governments in countries with more advanced solar energy sectors are pushing manufacturers to take responsibility for recycling their panels."

Germany, Europe's leader in solar panel recycling, can already process up to 96% of expired panels. The remaining 4% consists of materials that are still too difficult to separate — but even that's set to change.

"Europe isn't just supporting recycling companies; it's also investing in new solar panel tech to ensure that they can be recycled 100% in the future," says the Greenpeace Ukraine co-leader.

Ukraine still has time to get this right. Solar energy started gaining traction here after 2010, much later than in other European countries. And the panels currently in use have long lifespans.

"On average, a solar panel lasts around 32 years. Manufacturers say that after 30 years, energy output drops by 20%, but in reality, the decline can be even smaller," says Polina.

Ukraine doesn't need to start from scratch — it can learn from countries that have already figured this technology out. With a coordinated effort from the government, solar manufacturers, installation companies, and farmers, Ukraine has a real shot at making agrivoltaics a sustainable and efficient part of both agriculture and energy production.

We created this feature with the support of Journalismfund Europe.