What is the problem?

"In 1947, my grandmother and her whole family were deported to Komi ASSR, an autonomous republic in the northwestern part of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, because of her pro-Ukrainian views," student Yaroslava Hubova tells Rubryka.

It was a long and exhaustive journey. People were transported in wagons for livestock, where Hubova's great-grandfather died. They were deprived of water and only given fish and a bread loaf a day. Upon arrival, Hubova's grandmother tried to escape, even managed to catch some trains, but ultimately was sent to Komi again.

Hubova's grandmother was born in Transcarpathia but could never return home. For many years, the family lived in Karaganda, a city in Kazakhstan where she fled. Deportees were banned from returning to their hometowns and villages, and were usually resettled to Ukraine's eastern and central regions — that's how the family turned out to be in Dnipro. "This is what it is, the deportation of people loyal to their homeland and people. This is a prison of people faithful to truth and will," Hubova's grandmother shared her story.

Photo: heroine's family archive

Photo: heroine's family archive

There are tens of thousands of such stories. In 1939 alone, about 1.2 million people were forcibly deported to Siberia and Central Asia. Roman Teslyuk, a leading researcher at the Holodomor Research Institute of the National Holodomor Genocide Museum, notes:

"After the end of World War II, the totalitarian communist regime, unfortunately, was not condemned by the world, which allowed it to continue the practice of extermination and subjugation of the population of controlled republics.

In connection with the accusation of the Crimean Tatars of collaboration with the Nazis in May 1944, 191,000 Crimeans were deported from Crimea to the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic and some regions of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic. Together with Crimean Tatars, Greeks, Bulgarians, and Armenians, about 37,000 people in total were evicted from Crimea.

The forced deportation of Ukrainians continues to this day in the temporarily occupied territories. According to Ukraine's President, Volodymyr Zelensky, as of 2022 alone, Russia has forcibly deported more than 1.6 million Ukrainians.

Deportation is one of the factors that confirms Russia's colonial policy towards Ukraine, where Russia acted as an empire for years, enslaving almost all countries around it, including Ukraine. Tetiana Filevska, creative director of the Ukrainian Institute and a researcher of Ukrainian art, says: "For a long time, Russia was not recognized as an empire, and Ukraine as a colony." However, historical events — genocide, forced deportation, destruction of the intelligentsia, and the Ukrainian language — are facts that testify to Russia's efforts to destroy Ukraine as an independent state.

For a long time, the pro-Russian government of Ukraine only strengthened Russia's imperial influence. For example, in 2010, then-President Viktor Yanukovych declared, "It is unfair to recognize the Holodomor as a genocide of Ukrainians." Due to the misunderstanding of Russia's motives and the pro-Russian inclinations of the then-Ukrainian authorities, the war in Ukraine, which began in 2014, was considered civil by the world until 2022, when Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Despite this, it is difficult to eradicate Russia's significant century-old influence immediately. It took root in many manifestations: Russian street names, monuments to Russian poets and artists, the imposed Russian language and culture on Ukraine's territory, and the long-term attempt to destroy Ukrainian identity through the gradual destruction of its regions.

What is the solution?

Colonized countries are faced with the question of how to restore their own identity along with territorial integrity. Life in colonial politics inflicts trauma on society, after which it takes a long time to recover.

This is how the movement of decolonization appeared in global processes. Tetiana Filevska describes decolonization as an attempt to free ourselves from imperial influences and violence. These processes should happen not only at the state level but also at the level of each person's life. Ukraine's decolonization at the state level began with decommunization and de-Russification. Individual ones take place at the level of a single person, their attempts to abandon the culture, language, and narratives imposed by Russia. In these processes, the words of Roman Ratushnyi, Ukrainian journalist and public activist who died defending Ukraine in June 2022, "kill Russia in yourself," acquire new meanings.

The more we talk about the effects of colonization on Ukraine and the cultural codes that were tried to be destroyed, the more likely Ukrainians will be able to recover over time. The more Ukrainians talk about their true identity and not the prism imposed by Russia, caricatured and colonial, the greater the chance to separate from Russia in all respects and win the war. The struggle for one's own identity has been passed from hand to hand by all generations of Ukrainians for centuries.

How to restore the region after the consequences of colonization — to restore its identity

The first step to recovery is admitting a problem and dealing with it, or, in other words, talking about decolonization. This is exactly what the volunteer students who united at the training program on decolonization in Ukraine created the idea of the "Portraits of the Luhansk Region" project did.

Yaroslava Hubova. Photo from the heroine's archive

Hubova, a team member originally from Dnipro, shares that she thought a lot about her region during the decolonization training. "We want to decolonize the Dnipro region. After all, this is such an interesting and authentic district about which no one knows anything particular. However, I will have time to speak about Dnipro. It's time to shout about Luhansk."

The volunteers set themselves the goal of researching the primary culture of the region and telling about it in a frame through portraits of ordinary people, their stories and pains, their intentions and faith in Ukrainian Luhansk.

How does it work?

"We must shout about the Luhansk and Donetsk regions because we are fighting for them already now"

"In our work, we want to show what exactly we are fighting for in the Luhansk and Donetsk regions, what is important about them, why we cannot all give up in this war," says Hubova.

The volunteer believes that the authentic culture of the regions was dulled with the arrival of the Soviet Union, which erased the culture and "hid it in a closet." Filevska, a researcher of Ukrainian art, agrees, as she recalls, that Russia successively destroyed Ukrainian culture, and everything that had value for Ukrainians ended up in the metropolis, a country that owns colonies. In particular, Ukrainians still do not have access to a significant part of the archives with Ukraine's history because they are concentrated in Russia.

"Put aside the burden of colonialism and remember our own to show that we have nothing in common with the Russians. Luhansk region has never been Russian and cannot be Russian," the student adds.

At first, the project's idea was to create a map of Starobilsk in the Luhansk region and reproduce in digital form the ancient cultural heritage that has not survived to this day. However, the team decided to settle on the idea of creating a series of documentaries and films about the Luhansk region and its inhabitants—short nostalgic memories from people who tell what makes this region special for them and how it differs from others.

People who support their region and are carriers of its culture have become heroes — a Ukrainian language teacher from the city of Popasna who decided to teach Ukrainian in a Russian-speaking environment, a volunteer of the Brave to Rebuild initiative, who saw the occupation of Luhansk, an artist from Siverskodonetsk who paints pictures dedicated to this city, a journalist of Eastern Variant media, who writes about the Luhansk and Donetsk regions, an archaeologist who worked in a museum in Starobilsk, a cultural activist from Kadiivka, who moved to Starobilsk after the occupation of the village, and other heroes.

Hubova shares that the project's name, Portraits of the Luhansk Region, reflects its values — not to talk about general things but to visualize the history and image of the Luhansk region through the prism of a personality.

"We focus on people, personalities, memories, and thoughts because culture is formed by people, and it changes thanks to people," the student says.

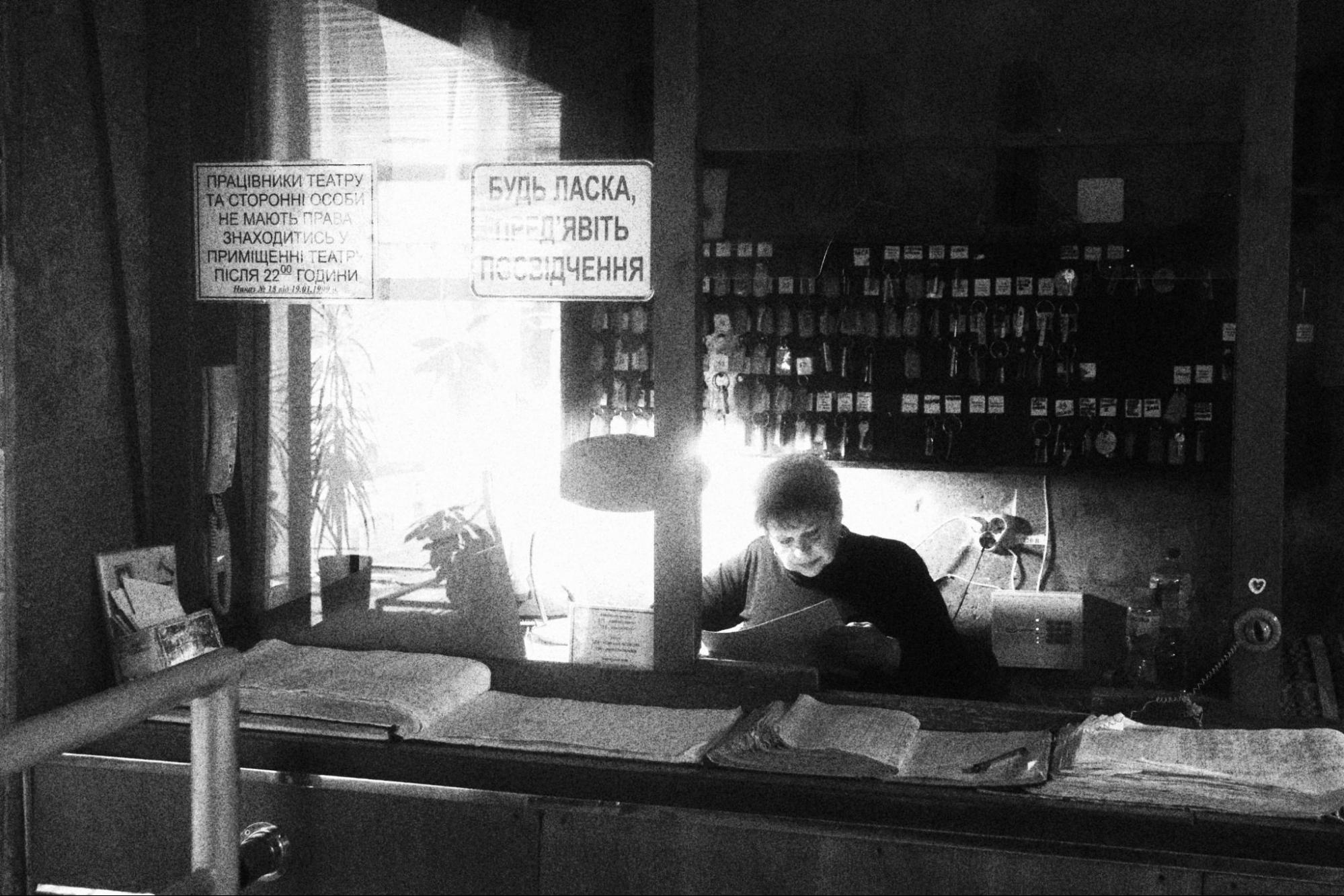

About the Luhansk Theater

The Luhansk Theater became the hero of the team's first documentary short film. Its story began in 1941, when actors evacuated from various regions of Ukraine were sent to work in the Caucasus. In 1944, the troupe was re-evacuated to Voroshilovgrad, now Luhansk.

The Luhansk Theater is an indicator of the region's Ukrainianness and authenticity. The theater performs classical Ukrainian performances and began to Ukrainianize the population in Luhansk even before the war in Ukraine's east in 2014 and after when it relocated to Siversko-Donetsk. There is a myth that the Ukrainian language and everything Ukrainian was not accepted in the Luhansk region but the very fact that the theater staged plays in Ukrainian disproves this statement.

Theater team. Photo: archive of the heroine

Oleksandr Gryshkov, director and artistic director of the theater, recalls in the film that after the occupation of Luhansk in 2014, the troupe was divided into three parts. One remained in Luhansk and continued to cooperate with the occupiers, another part went to Russia, and the third went to free Ukraine.

"We have to show that if the territory is physically occupied now, it does not mean that Luhansk is not there," says Maxym Bulhakov, the theater's chief director. "Do you understand that this is a struggle of civilizations? And the basis of any civilization is culture. If there is no culture, there is no civilization and nothing to fight for. The citizens should not identify themselves with the Soviet Union but identify as Ukrainians, andunderstood why we live and fight.

Photo: the heroine's archive

"I think memory is about shaping the future"

In many ways, decolonization is about reflection and rethinking — a reflection of history, culture, heritage, and what happened and is happening. The Portraits of the Luhansk Region project team chose a documentary as a reflection method.

"Documentaries are essential and advanced because they capture reality and broadcast it. Now, it is important to show Russian crimes and how Ukrainians are fighting back, to send certain messages, and to show them abroad. This is one of the ways to shout about Ukraine," says the student.

Hubova adds: "Our film is about theater and art, but it cannot be done outside of the context of war because it exists in this context. Documentary cinema is about approaching objectivity, and you can't throw out the contexts of today. You can't not make a movie about the war in a country with a war."

Restoring identity is a long process that will require more than one discussion and will take more than one year, especially in the conditions of a struggle for one's own life. The Russians continue to shell Ukrainian cities and villages every day to destroy Ukrainians as a nation. The only way to avoid it is to remember the wrong committed, not to dare to forget it, because "memory is about shaping the future."