Zaporizhzhia has a logistics hub for internally displaced persons (IDPs) on the city's outskirts. Buses and cars arrive here with those lucky enough to leave the occupation every day. Their road to freedom is always tricky, often taking more than three or four days. In the hub, migrants have the opportunity to eat. There is a medical center and rooms for children. Volunteers work here to help with further travel around Ukraine or abroad.

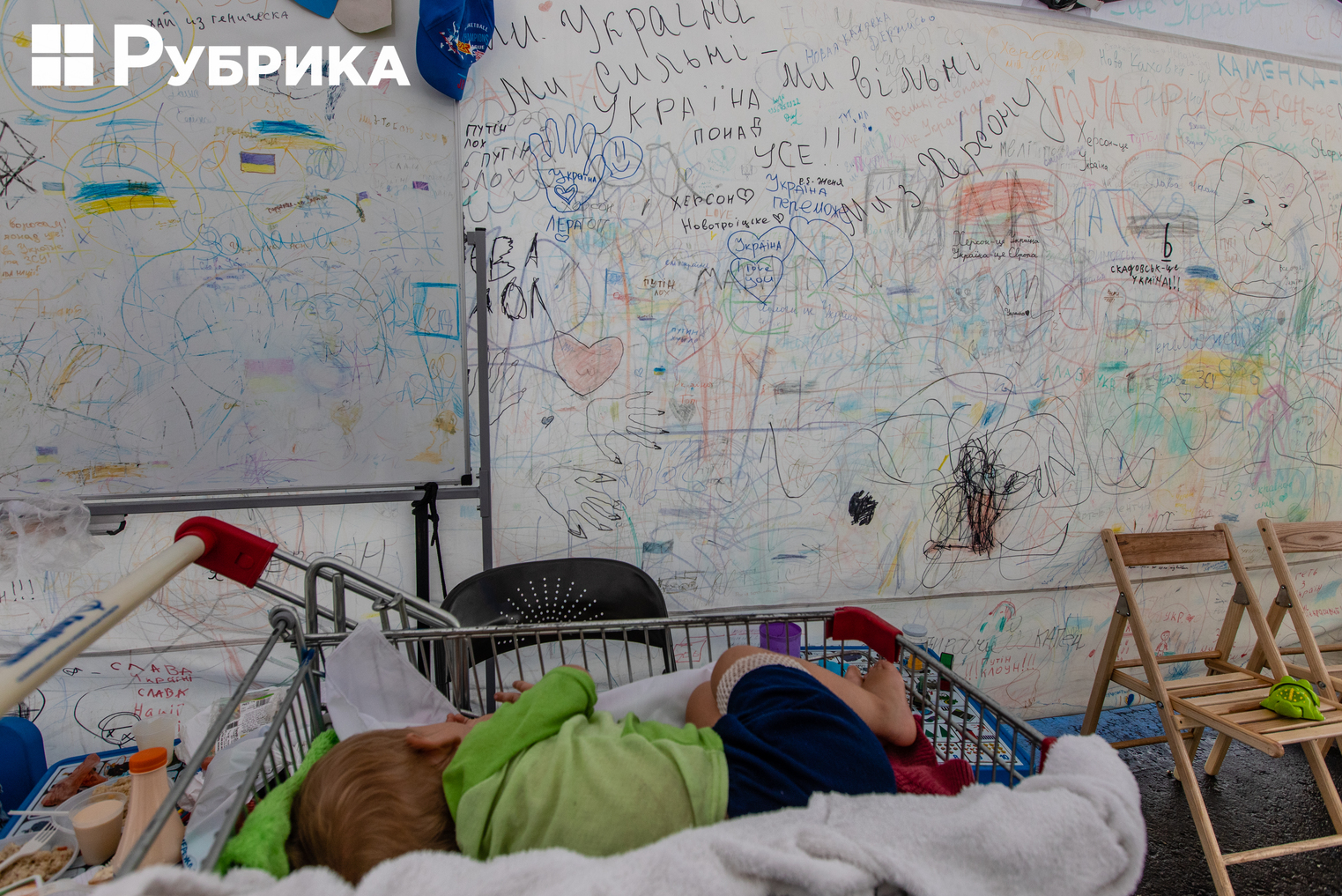

Baby in a cart

A supermarket cart stands in one of the open tents. The baby sleeps in it. Nearby, the child's mother, Anzhela, is talking to an unfamiliar woman who's crying. Anzhela tries to comfort her. A few days ago, Anzhela and her baby left Berdiansk. They are currently living in temporary housing, and the next day, they will get accommodation in Zaporizhzhia. She asks not to photograph her face but allows us to take a picture of the sleeping baby. He sleeps near a wall on which children draw and write various wishes.

Anzhela says, constantly looking in the direction of the child:

"We lived in Berdiansk for 12 years. The eldest son went to school there. We had a normal life. After the occupation, everything changed. It became impossible to live there. Prices for everything have risen sharply, and it has become impossible to support children; you earn money only for food and can't afford anything else. There's constant pressure from the city administration; they want to force residents to send children to russian schools and threaten. My husband left a month ago and now works as a driver, transporting grain. We drove for four days; we applied for evacuation, were picked up by bus, were lucky, and were driven away for free. In Vasylivka, we waited for our turn for a very long time. First, we were the 159th in line, then the 74th, the 34th, and finally, we left the next day. I thank the bus driver, who took mothers and children to a friend's zoo; we found shelter while waiting our turn. We were fed, there was water, and we rested. And it was much more difficult for others in line to wait several days on the street in such heat.

My first feelings when I passed the Ukrainian roadblock were cheers and the feeling of freedom. We are in Ukraine."

"Our village is occupied. They are shooting from there"

Nearby is a large tent with a kitchen and volunteers looking for accommodation and route options. Several dozen people are waiting for buses with their belongings in the shade. Let's meet Tania, her husband Dmytro, and children Artur and Mykyta.

"We are from the village of Velyka Znamianka. Zaporizhzhia region. Our village is occupied. They [russians] are shooting from there. The village wasn't seriously affected, though there was shelling. We feel it, but we do not see them [russians]. They are somewhere on the outskirts, and we live in the center. Less than half of the people stayed in the village. Work is hard, and it's difficult to talk to the administration; if a person comes to you with a machine gun, you don't want to say anything against it. You keep quiet."

The family was leaving the occupation for three days. Tania says:

"The first time we left, we stayed [in convoy] for two days, then went home so the children would not be in the heat. We waited, but our driver from the Melitopol side couldn't find a way to pass the russian roadblocks. Then we left from the other side, from Dniprorudne. There was a huge convoy; we drove a little, ten cars pushed forward, then stopped. People who bribe have an easier road. Those who don't give anything stand in line and even go to fight. We didn't need to get a permit for departure, but they say it will be necessary to issue a certificate for departure from Monday. We plan to go to the Kirovohrad region; my mother is there. We will look for jobs since we need to feed our children; we need to find a school," Tania sighs and adds. "When we saw the Ukrainian flag, our hearts felt lighter, tears flowed."

"The cruelest ones are our own, recruited to police with ads"

Next to them is another family from Nova Kakhovka. These are Andrii, Sveta, and their children, Andrii and Sasha.

"As soon as we have an air raid alarm, our children have already hidden in the basement. And I haven't even put on my slippers. The bombs scattered throughout the district when the Ukrainian troops blew up a [russian ammunition] warehouse in Nova Kakhovka. The explosive wave shattered our glass. russians say that residential buildings were damaged, but that is not true. The houses were damaged only by the large blast wave from the detonation of the shells. The warehouse was in an abandoned industrial zone, and only things that had been abandoned for a long time were destroyed there. They were furious after the explosion. They began to open basements under people's houses and settle in them, and they kicked people out of bomb shelters. They are terrified. In general, the city was emptied after that explosion. And after the Ukrainian forces blew up the Antonivka bridge, equipment is now transported through the hydroelectric plant bridge mostly at night," says Andrii.

The man recalls that at the beginning of the occupation, there were many "Donetsk People's Republic" soldiers in Nova Kakhovka. "Then the paratroopers appeared, Chechens or someone else, I don't know, definitely not russians. They constantly get drunk and fight among themselves. But in general, the cruelest ones are our own, recruited to the police with ads. They kill locals in the basements; that's how they behave. Former police officers did not go to the new police. All sorts of people enlisted were people who had been kicked out of the police earlier, as well as various drug addicts and previously convicted. At one point, they were even banned from selling alcohol in the market because they got drunk and started shooting at each other. Recently, one girl was taken to the basement, severely beaten, and tortured with an electric shocker. She was lucky, as she is Israeli, and she was released. People sit in basements for three days, two weeks, or two months."

The couple says that, among other things, it is tough to find work in the occupied territories. Andrii says: "The factory where my wife worked is being pressed. russians are demanding that the owner get a russian passport and switch to russian registration. Of course, he doesn't want to. The prices are generally astronomical for everything, except for vegetables, which are nowhere to get rid of because before, they had been sold all over Ukraine. They bring goods from Crimea, so the ruble prices are put in hryvnias."

There are problems, of course, with educational institutions. "Of all the schools, it seems that three will work. The russians threaten that parents who don't send their children to school will be deprived of parental rights. There are those in the city who are pro-russia. They say that Ukrainians bomb and don't care about people. You tell them our army hit warehouses, and those explosions break your windows. What would you say about living in Mykolaiv, Vinnytsia, or Kharkiv? Yes, of course, it had been silent for a long time. Only recently, it became loud when they began to destroy russian warehouses. But it will be worse when the city is liberated and the russians start to shell us from Crimea. What do you say then? Two families in our building hung russian flags, and the men went to work as the police. If I start to say something and want to prove myself right, the mother from one of these families will immediately tell her son that they will come and take me to the basement, and I have two small children. I don't want to go to the basement. Whether you will get out of there or not is unknown.

When we broke free, we had tears in our eyes. Today we are going to Lviv, and I don't know where life will take us. I think there will be no turning back. But we're in Ukraine. We have our people around, and we will survive."

Photos and fear for relatives

The following person we talked to agreed gladly to speak but refused to be photographed. In general, many people with relatives left in the occupied territory are afraid for them; they are worried that their stories will be read there, their photos will be seen, and their relatives will suffer.

Her name is Larysa. She lives in Tavriisk, Kherson region. She explains that it is between Kakhovka and Nova Kakhovka.

"I was leaving for a very long time. We went on the 28th (of July, ed.) and only arrived here on the 31st. We hired a carrier. Is it expensive? Well, what to say? For some, it is costly; for some, it is not, depending on income. For someone, it is worth almost nothing; for someone, it is a month of life.

Life is complicated. ATMs have stopped working, and you can't withdraw money from the card. A lot of people left. Primarily those with nowhere to go or nothing to pay for the drive stay. Mostly older people stay, but there are also young people because their families are enormous, and they have no money. I live in the private sector. Our street is almost empty," Larysa recalls.

The woman says the worst thing is the explosions, and because of them, she left. "The explosion seems far away, but everything is equally scary. Especially when there was the explosion in Nova Kakhovka (that explosion at the warehouses became legendary, almost everyone we talked to spoke of it as very big and important and called it "the explosion in Nova Kakhovka," ed.), my house windows were blown out by an explosive wave. The depot was so big, so it exploded all night.

Now I'm going to Odesa; I have relatives there."

"Maybe we're carrying a Bayraktar in panties?"

Natalia is from Chornobaivka. The same one that has already become legendary for Ukrainians. Now she is on her way to Odesa with her daughters. She says that the road from the occupation is complicated and lengthy, and also very expensive. Private carriers charge 10,000 hryvnias per person—it doesn't matter if it's a child or an adult. Natalia could not take her mother out; there was not enough money.

"It's deafening in Chornobaivka," Natalia says. "When the warehouse with ammunition was blown up, the shells scattered all over the village. It's good that we were in the shelter; no one was hurt."

The russians pretend that everything is fine. Pensions were raised, and 10,000 rubles were delivered to the homes of people who cannot walk—five to six thousand hryvnias. My company offered a salary of 37,000 rubles, much higher than the minimum of 6,700 hryvnias I received, but I did not accept. I cannot work for them. In general, they do everything with a carrot and a stick.

On the one hand, they offer more money. On the other hand, you are afraid to say a word or say hello. Even just leaving the house is scary. We live next to the store; russian soldiers constantly come there with weapons and buy food. While standing in line and waiting, they drink beer. Who can be sure that they're adequate? I was afraid to let the children go to the store. And not only that. The children were in the basement almost all the time. They even ate there. I was afraid that the russians would not see that I have teenage children. It was terrifying for them."

Natalia also remembers how once, while she was at work, her house was robbed: "There was no mobile service, my friends came to me, they said that the house was being robbed. I ran; the gate was open, and the garage was empty. Two children's laptops and a children's speaker were stolen. I went into the room; I saw that children's things with tags were scattered. They took photos and sent them to their wives, whether they should take them or not. Once they took my mother, she was already in her sixties. They drove her around, scared her, took her phone, and let her go.

It hurts my soul that there are so many traitors. You knew them, talked to them. If you want to live in another state, if you don't like living here, sell your house, you will have money, and go to any country and live there. You shouldn't bring a foreign state into our country. It is a pity that there are many collaborators, traitors, whom I could not think of suspecting."

According to the woman, russians also have lists of those who have children. They call the parents and say that according to the Geneva Convention on the Protection of Children, they are supposed to educate the children during wartime. "And I don't want them to study in a russian school. And if I don't let the children, I will be deprived of parental rights, and they will take them to russia."

russian soldiers still tell locals that they "came to liberate them." Natalia recalls:

"We lived in the basement for two months, then left for the country. They also came to our country house. 'Where are you from?' I ask. 'We are locals.' Do they already consider themselves local on my land? I think maybe they're collaborators. And then he approaches, plucks a currant, and asks: 'What kind of berry is this?' I say, 'Guys, it's a good berry, eat more. It's beneficial." I said in a tone that he got scared and threw it away. Yes, he's local, all right! Then they came to us again, and I stood by the stove. He asks if there are men at home. I say it's just the children and me [in Ukrainian]. And he asks: 'What?' I say [in russian]: 'Children, I have two girls.' It's funny now, but then it was horrifying. They cut down all our apple trees and put logs in the T-shirts that they tugged up. They were not ashamed that there were two children. They're like locusts."

Remembering all this, the woman is indignant: "Why should I get someone's permission to travel on my land, in my country? Many people ask: for what purpose are you leaving? Why should I report to you? Because you have a machine gun? Did they come to liberate me so I could ask them for permission about where I should go? You know, there is a phrase, 'How well we badly lived." Now we understand it."

The road to the controlled territory seemed difficult: "We got to Vasylivka quickly, got on the bus at half past eight, and were there at four o'clock. We arrived, and there was horror, heat, and garbage everywhere, just mountains of garbage. The next day, we asked the russians for garbage bags and cleaned there. The first night was terrible. We had a small Bogdan-type bus, it was overcrowded, and we spent the night in it. My girls didn't even sleep; they were walking around. The next day they let us into the refrigerator trailer. We slept on cardboard, but we could lie down, albeit it was hard."

The bus stayed in Vasylivka for three nights and four days. The russians checked everything and turned things on the ground: "I don't know what they are looking for. Maybe we're carrying a Bayraktar [drone] in panties? (laughs). All men are undressed in front of everyone; russians are looking for tattoos. I was lucky, and they didn't check my purse because I had so many things that while they were opening everything, that soldier got scared from the number (laughs).

When the driver said, 'Girls, we are in Ukraine,' we all cried. We shouted and rejoiced. We hugged our soldiers at every checkpoint. In the evening, we sat down to eat and washed our hands, and my daughter said: 'Can I not wash this hand? I touched a [Ukrainian] soldier with this hand.'"

Natalia mentions that russian equipment is constantly exploding in Chornobaivka; "they are constantly concentrating there for some reason."

"You go out at night and hear the hum of machinery driven there. And they are constantly blown up. There are sewage plants, an airfield, and various overgrown areas. They constantly put a lot of equipment in those thickets. They also mine all the fields around. And when they go around the village, they like to shoot into the sky with a machine gun, just for fun."

Newsletter

Digest of the most interesting news: just about the main thing