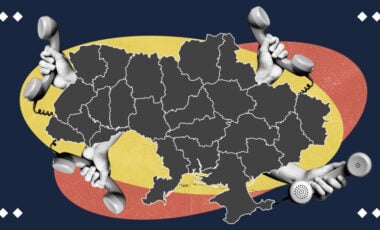

Ukraine's ally plus "putin's friends": what to expect from new Italian government

"The return of Mussolini" and "the first far-right leader in Europe after World War II"—this is how Western observers reacted to the results of Italy's September elections, where the center-right bloc led by Giorgia Meloni defeated the center-left and liberals who supported incumbent Prime Minister Mario Draghi.

She will head the country's government, although she has an unusual biography. Judge for yourself: she was in the neo-fascist party MSI; in her youth, she praised the dictator Benito Mussolini and then putin and spoke against the "LGBT lobby." Meloni also threatened to take Italy out of the Eurozone and believed in a conspiracy theory that someone wanted to populate her country with migrants instead of Italians.

Rubryka has followed the situation after the elections and can explain what Italy will be like with the new government. Spoiler alert: no, the days of Mussolini are not coming back.

The victory of the right bloc in Italy was really tangible. Fratelli d'Italia or Brothers of Italy, led by Giorgia Meloni, received 26% of the vote, Lega or League, led by Matteo Salvini, has almost 9%, and Forza Italia or Forward Italy of Silvio Berlusconi (yes, the same one) got 8%. However, the last two parties have failed compared to the 2018 elections. League lost 87 mandates, and Forward Italy lost 98!

But together, political allies won 44% of the votes in the elections to both chambers (Italians vote separately for senators and members of the Chamber of Deputies but almost always give two votes to the same party).

Now the center-right will have a clear majority and form the government. The triumph of the "Brothers" means that Meloni will become the absolute leader of the new government. So attention is focused on her.

Nevertheless, Italian observers are calmly discussing a change of government, the economy, and pensions and are by no means preparing for a fascist dictatorship. Meloni is treated differently, but experts do not see her as a future totalitarian leader.

Meloni renounced her fascist views, and Italians loved her for something else

After all, the politician herself has become more sensible over the years. For example, Meloni publicly condemned the anti-Semitic laws and the collapse of democracy under Mussolini, and before the election, she expelled a party colleague who praised Hitler. Now she says that fascism has long been "consigned to history" and calls herself a conservative.

Meloni has already worked with the International Republican Institute and the Aspen Institute and even spoke to American conservatives. In short, the future prime minister has had new models in politics: not fascists, but the US Republican Party and British conservatives.

The politician has already declared that she will not repeal the laws that allow same-sex marriage and abortion, although she fiercely criticized them during the campaign. That is, she promises to separate her personal views and politics.

And most importantly, Italians voted not so much for the ideology of the "Brothers" as against all those in power before. They could be pushed to do so by economic problems: tariffs and inflation are rising, it's increasingly difficult for people to find work, wages are decreasing, and businesses complain about bureaucracy. Meanwhile, the country's national debt is 150% of its GDP, so Rome is forced to ask for money from the EU. Otherwise, the Italian economy will not survive the winter.

As expected, the citizens believe that the "predecessors" are to blame: in recent years, the ruling coalition has included the center-left parties, the parties of Salvini and Berlusconi, and populists from the 5 Star Movement, in short, everyone except the Brothers of Italy, who always remained in the opposition. So, the average Italian has fewer complaints about them. The desire to "replace everyone" will remind Ukrainians of the 2019 elections.

"We tried everything else, and it didn't work. We have to give her [Meloni] a chance," The Guardian described the mood of the voters. In addition, many voters saw the "Brothers" as originating from the common people, not the "elite." After all, Meloni grew up in a working-class neighborhood and worked as a nanny, waitress, and bartender to make ends meet before becoming an MP.

Actually, the economy was the primary topic during the elections. The word "Ukraine" sounded loud only once when Giorgia Meloni published a video where a migrant from Guinea attacked a 55-year-old Ukrainian refugee. This is how the politician wanted to show voters: migrants are dangerous and that her party would "restore order" if it won.

Meloni was rightfully criticized (posting videos of violence, even without the victim's consent, is unethical), but Ukrainians may not worry. The future prime minister is not against our fellow citizens.

Meloni supports Ukraine, and "putin's friends" in the coalition are losing influence

"An unacceptable large-scale act of war by putin's russia against Ukraine" was how Giorgia Meloni called the russian federation's invasion long before the elections and called on the government to arm Ukraine. Her sympathies have long been on the side of Ukraine, and it is an unusual position for the Italian right, who are traditionally friendly with Moscow.

As it turned out, the victory only strengthened the future prime minister's determination. After winning the elections, she called Volodymyr Zelensky to assure him that Ukraine could count on Italy's support. She called russia's attempt to annex Ukrainian regions a "neo-imperialist" and "Soviet" approach.

For us, it means that Meloni's government will continue the policies of its predecessor, Mario Draghi. Then, let's recall: Italy supplied weapons to Ukraine (although not as actively as the UK or the US), supported the EU sanctions, and seized russian accounts. The most crucial issue is the sanctions because Italy could stop them if it wanted to, using every EU member's right to veto.

By the way, it wasn't always like that. Back in 2021, Meloni praised putin, saying he defends "European and Christian values." In general, European far-rights have often admired russia: for example, same-sex marriage is not legalized there.

What has changed? Perhaps, after February 24, Giorgia Meloni felt solidarity with Ukraine, waging a national liberation struggle against the conquerors (it would be logical for a nationalist). But there are more serious reasons.

Meloni is a zealous supporter of the alliance with the USA, and in general, the Brothers of Italy see their country as a reliable NATO member. The position of the United States is known. Washington supports Ukraine, supplies weapons, and seeks to attract as many other countries as possible to our side. So if Italy "goes the other way"—refuses to help Ukraine and blocks sanctions against russia in the EU or NATO decisions—Meloni's government risks harming relations with the US (as well as with the UK and other members of NATO).

In addition, the future PM has already promised to stay on the side of Ukraine, so changing her views on the fly would harm the image of Meloni herself. "The far-right leader's support for Ukraine against Russia is part of an effort to move from radical to respectable," Politico reported.

Those, really historically gravitating towards russia, are Meloni's coalition allies. The leader of the League, Matteo Salvini, is suspected of conspiring with the russian federation to overthrow the previous government (!), and he was photographed in a T-shirt with putin. And Silvio Berlusconi recently said that russia simply wanted to capture Kyiv and replace Zelensky with a "government of decent people."

But there are two "buts" in our favor. First, after russia's invasion, open support for russia has been a taboo even for Salvini and Berlusconi (the latter already had to apologize for his statement). Second, League and Forward Italia will be junior coalition members, so Meloni's position will remain fundamental.

New government doesn't plan to create crisis in EU and distract it from supporting Ukraine

Indeed, during the campaign, Meloni used slogans such as "no to bureaucrats from Brussels" and "the good times for the EU are over," saying that the European Union is no longer the same and generally imposes its demands on Italy. However, as soon as it became clear that the Brothers of Italy would win the elections, the party slightly changed its position. Now they assure the European Union of their loyalty and promise not to destabilize the bloc. However, Meloni insists that Italy will put its interests above the EU.

According to Dario Christiani, a Marshall Fund expert, the new Italian government policy will be similar to the Polish one. We will remind you that Warsaw often has conflicts with the European Union but always finds common ground with Brussels on critical issues such as the EU budget, sanctions, or energy. And it doesn't threaten to leave the European Union.

Such a turn could also be an attempt by the "Brothers" to drop the "fascist" label and prove that they are respectable conservatives. At the same time, the issue is the economy. To get out of the economic crisis, Italy needs additional money. European Union is ready to provide it, and we are talking about hundreds of billions of euros.

However, Brussels set conditions for Italy: first, the government must complete 55 "homework tasks," and only then will it receive a new tranche. It will remind Ukrainians of the relationship between our government and the IMF. Therefore, the new government cannot fight with the EU or, for instance, adopt a budget that contradicts the rules of the European Union. Then Italy will not be sent a tranche, the crisis will intensify, and the citizens will again want to change the government.

By the way, the role of the EU also guarantees that Meloni will not be able to promote any dictatorial laws, even if she suddenly wants to, all because of the risk of running out of money.

However, there are many political threats on Meloni's path

How Meloni copes with the "homework" will become apparent in November when the center-right coalition forms the government. Despite the evolution of the Brothers of Italy and their leader, observers predict many problems for them.

First, the coalition is far from monolithic. The three parties held together to come to power, but they had different views on what to do next: for example, how much autonomy to give the regions, how to change the pension system, or pay people a basic income.

And suppose Meloni has to carry out unpopular reforms (for example, to stop inflation or fulfill EU requirements). In that case, it remains to be seen if her current allies support her or if they organize a new "coalition." For Italy, such a change of government is a common thing.

By the way, the Ukrainian topic can also become aggravating. Matteo Salvini has long opposed sanctions—they allegedly harm the Italian economy. And since russian propaganda is in full swing in Italy, many citizens believe in it. So the League has a reason to criticize the PM and to demand to lift sanctions—at least to win over those voters who do not consider russia an enemy.

And Meloni developed a reform for which she is already criticized. The election's winner wants to change the Constitution, turning Italy from a parliamentary republic into a presidential one. We can understand the politician: in the last 20 years, the country has changed 11 governments. That is, it is difficult for the prime ministers to finish the reforms they started.

However, Italians consider a parliamentary republic an essential safeguard against the emergence of a Mussolini-style president-dictator. The opposition will seriously resist the prime minister, and the very idea can divide Italian society.

So we need to establish friendly relations with Meloni and her fellow party members before the new government gets too involved in Italy's internal affairs. Well, Volodymyr Zelensky has already invited Giorgia Maloney to Ukraine.