Photo: Rubryka

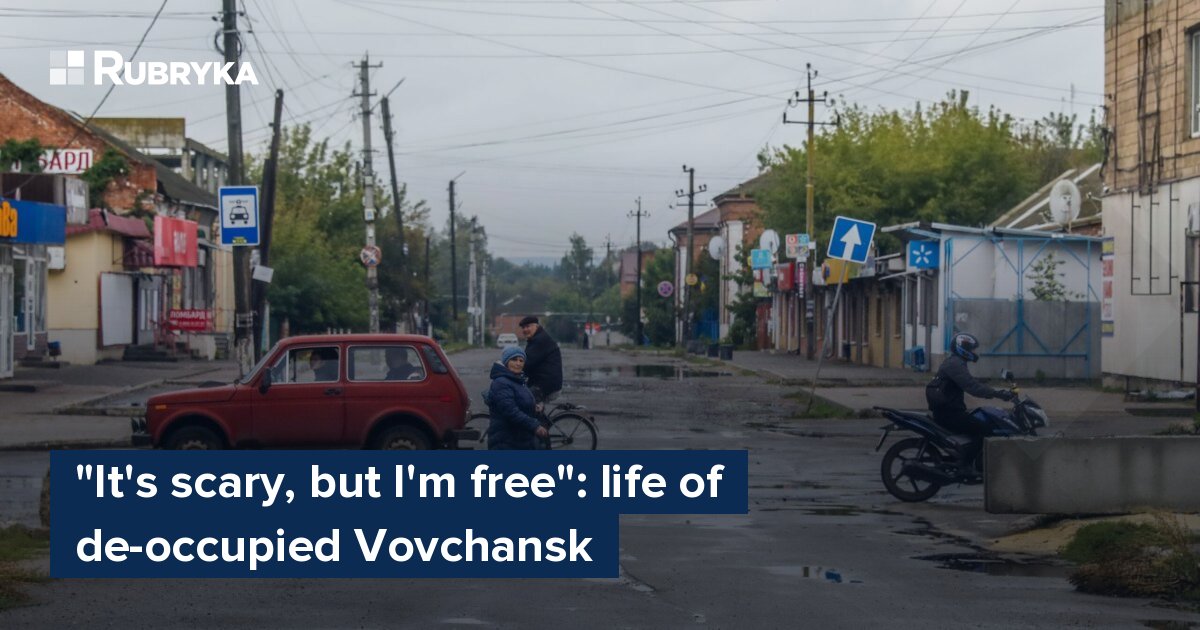

When the bridges across the Siverskyi Donets River weren't destroyed, the road from Kharkiv to Vovchansk didn't take even an hour and a half. Seventy-six kilometers pass, and you are there. Now we have to make a detour. Now it is a journey of about six hours, generously strewn with dangers. The road passes through Kupiansk, which is shelled by russian troops every day, and after Kupiansk, it approaches the border forests where sabotage and reconnaissance groups can hide. Almost all oncoming cars are either evacuees, volunteers, or soldiers.

Car in the ditch and cannonade sounds

The roads are destroyed. It seems that anyone can overtake us on foot. Although all the services work quickly—damaged and at least slightly usable russian equipment is taken away in a matter of hours—we still find something worth taking a picture of:

Nothing inspires as much as the destroyed russian military equipment.

Before reaching Kupiansk, we stop near a fallen stele painted in russian flag colors with the inscription Kupiansk Paradise. Spoiler: it was already restored the next day. Of course, now it is blue and yellow, as it should be.

Suddenly, we see a car flying into a ditch nearby. We hurried there and called the military on the nearby road. Two women who were in the vehicle escaped from Kupiansk under fire. They were nervous and lost control of the car. Fortunately, they were not injured. We help them, and together with the military, we change the wheel.

We pass Kupiansk to the sounds of the cannonade. The russians are constantly shelling the left bank of the city.

In the village of Sadovod, a little further down the road, locals decorated old Soviet sculptures at the entrance to the village. Now it is a meeting place for residents of this small village. Children sit on the pedestals of statues and greet the few cars that pass by—they are happy to see the Ukrainian military the most. Meanwhile, adults talk with each other. They say the village has been without electricity, gas, and water for four days. Shops are not open, and the pharmacy has been closed for a long time. Medicines are the biggest thing that residents lack. It's great that on September 16, mobile service returned, and locals can catch it right here, near the sculptures. While I am photographing children, mothers wonder who will see them. They are very proud of how they decorated the statues.

Vovchansk: the whistle of shelling

We know that there's no electricity in Vovchansk. On the ground, we learn that the Vodafone mobile service provider started working here less than a day ago. All those connected to other operators have free roaming. People now have the long-awaited opportunity to call their relatives freely.

Seven hours of travel, and we are in the city. It is already getting dark, and not a single window is lit; it seems that no one is left in the town.

The border with russia is four kilometers away. It means the night is not calm, and we hear the shelling all night. The russians even hit the city with mortars, directly firing residential areas from tanks.

The morning in the city begins again with shelling. But it doesn't stop the locals. Life here starts early: the daylight hours are constantly getting shorter, so every hour is essential. Among the locals outside is an older man who willingly talks to us about what life was like here during the occupation:

"I had to stay home; you can only go out to buy bread. I live in a private house with three acres of garden, where I can plant a bit. There were roadblocks all around the city. If you walk and don't see them, you lower your head. The russians often checked passports. Whenever you go outside, they say: show your passport. And then, they look at the residence permit. Unfortunately, many locals cooperated. I know that a criminal case has already been opened against them.

Once, some dressed-up russian Cossacks, or whoever they were, were here—in short, drunks. They drank heavily here. Then the mobilized men came from Luhansk. These soldiers were walking around with machine guns. Some behaved so importantly, and others were modest: maybe they were taken from some village and sent here.

The worst thing is that it was unclear what would happen next and when our troops would arrive. I have a satellite TV and have watched our channels. And from April 7 to June 10, we had no electricity. We hardly knew the news then. I used roaming to call my friends and ask what the word was."

A characteristic whistle and a mine explosion interrupt our conversation. We quickly go with the men to the nearest house to hide.

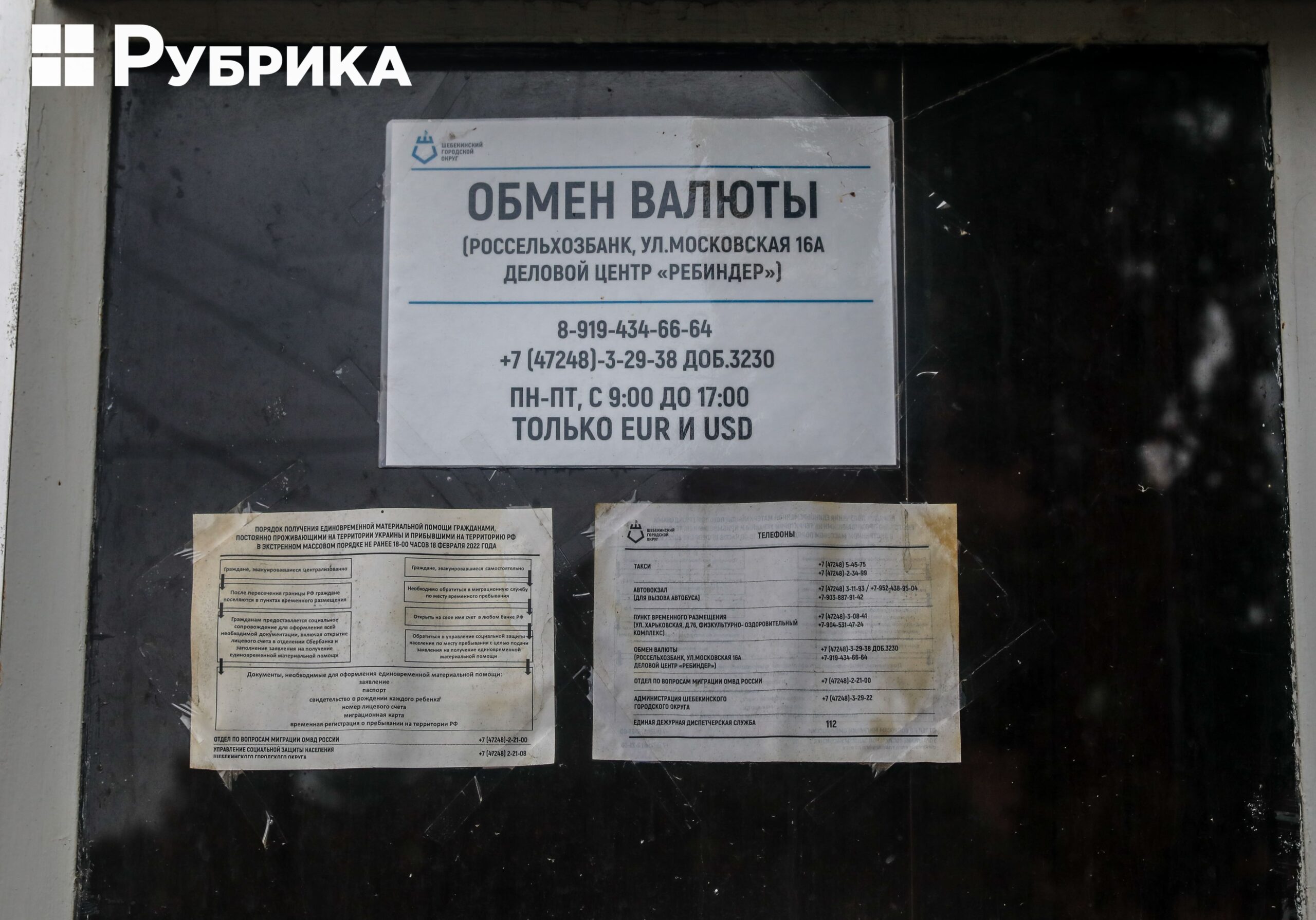

Vovchansk was occupied on the first day of the full-scale invasion. From April 7 to June 10, the city lived without electricity and mobile service. Pensions in cash were not paid. A prison worked in the town, where Ukrainian soldiers, former soldiers, and territorial defense volunteers were tortured. The occupation authorities tried to establish their rules: here and there, we come across currency exchange from a russian bank and various campaign materials.

But the primary rules that the russians established in the city were fear and terror. There were also high prices, and it was impossible to earn money through honest work for those who worked and for pensioners to receive pensions. Ordinary headache pills cost 60 hryvnias for six tablets (the average price is less than 12 hryvnias). You need to understand that the list of drugs available was tiny. It was almost impossible to get rare medicines, and because of this, the locals who needed them were doomed to a slow death.

"There was no bread, there was no yeast, and there was no flour"

Another local and two police officers joined us.

"The shells flew around at night. This bastard [russian soldier, ed.] comes out and shoots because he knows nothing will happen to him," says one of them. Then we hear explosions again.

"Our nerves were at their highest point all the time," says another man. "You worry: for grandchildren, for children, for everyone. Children and grandchildren live in Vilchy, a nearby village. We didn't receive a pension for seven months. Anyone who had bank cards could withdraw cash at a high-interest rate. It's good that my son helped, but I had supplies and a little bit of everything in the cellar."

The police officer adds: "It is challenging for those who live in the city if there's no garden. Whoever has it, life is easier."

The man nods and continues: "In the beginning, there was no bread, there was no yeast, and there was no flour either. We were worried about our son. The russians came four times and asked where the son was."

Everyone in the city also knows about the torture chamber the russians set up in one of the enterprises.

We hear an explosion again. It's unclear where; the sounds bounce off the buildings because it is a city.

A dog enters our building. Everywhere a war is, there are a lot of abandoned dogs. People evacuate but do not always take animals with them.

Remains of propaganda and russian products

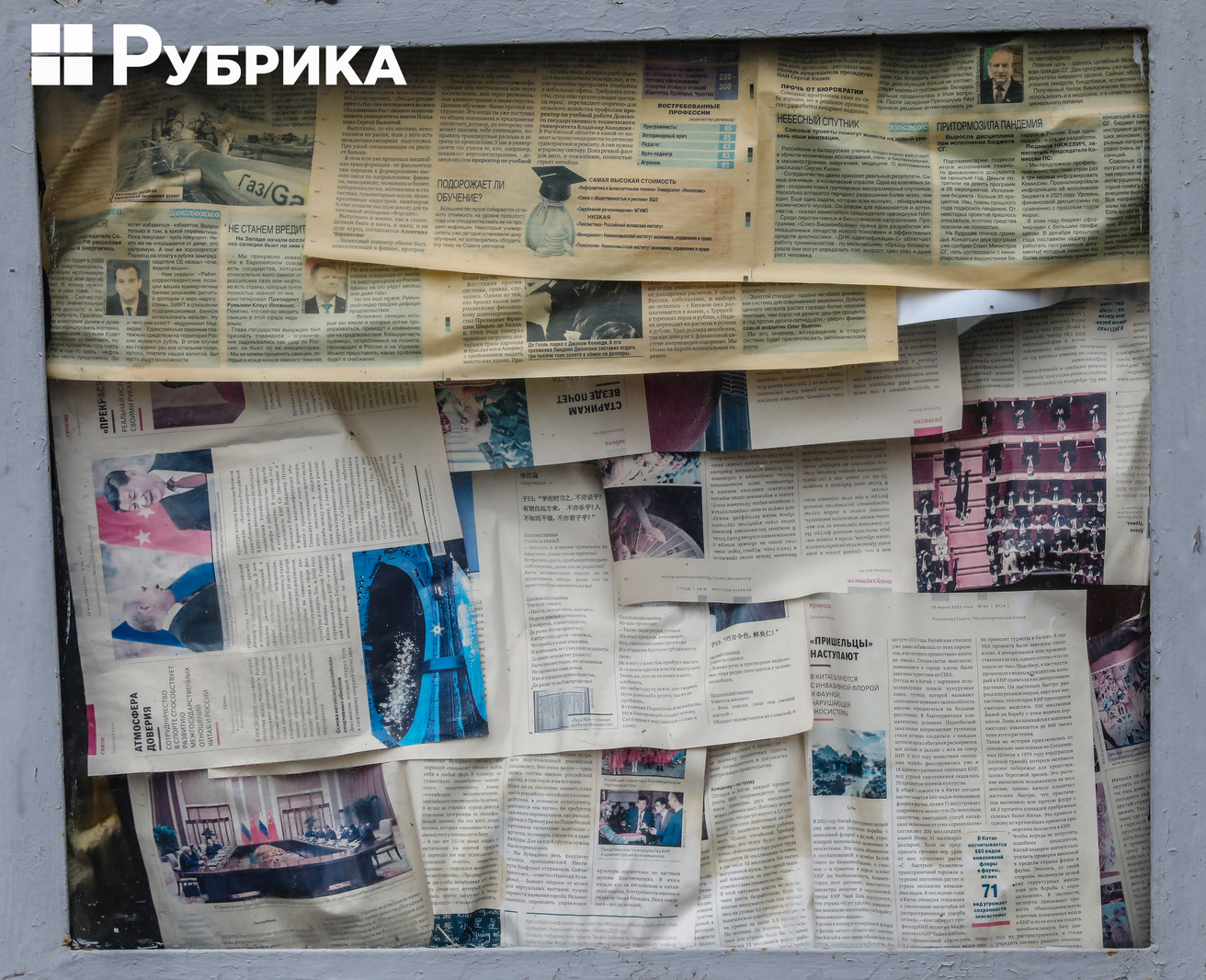

Only women with children were allowed out of the city towards Kharkiv during the occupation, and men were not. In the town, the russians actively spread disinformation—they said that "the Krakens (a special unit of the Ukrainian Armed Forces) will come and start raping the people." The russians also used the name of the Azov regiment to intimidate local people. Of course, it's difficult to believe in such a thing, but some had believed it then.

Let's go through the city—a police station and abandoned and destroyed military equipment with the letter Z next to a church. In the windows, there's propaganda and currency exchange advertising.

We see a large gate with the inscription "We work. Call us" in russian. There will be enough work for everyone after de-occupation.

Several shops are already open. russian goods are still sold at grocery stores—those that didn't spoil.

For now, the city has enormous problems with supplies. Even humanitarian aid hasn't been delivered yet. And the prices are much higher than, say, Kyiv prices.

Two women sell what grew in the garden. We buy a small bucket of raspberries from Valentyna.

The woman complains: "There is nothing: no bread, no medicine, no water, no food, all the shops were closed. There were russian medicines in pharmacies, but now they [russians] have run away, nothing works. Everything was expensive in pharmacies. We haven't received our pension for the eighth month. Everyone resold everything they had, and that's how we made money. russian soldiers didn't come to us. I live on the outskirts. Probably that's why they didn't touch us. While there was electricity—I have a satellite TV—I only watched Ukrainian news."

"The russians said they were here forever, but why are they bombing us now?"

We go further, accompanied by the military. We meet women, and they ask about evacuation:

"Where are people taken out? From our city? They say people evacuate from Kupiansk. Do they say that they will evacuate us? And what's in Kharkiv? Is it safe there? If we are driven there, can we go? Our little one is already completely disabled. They [russians] shell us around the clock. I'm trading at the market, and they started to shell. I thought I'd wait, dropped everything, and went home. When I get there, I see everything is broken and a hole in our door."

There is not enough information in the city. Due to no electricity, the television doesn't work, and there's no Internet. There are no newspapers or postcards, and the radio doesn't work. People are still under the influence of russian propaganda. Many are very intimidated. There are various rumors in the city, and everyone distorts the information; it seems that someone is doing it on purpose. We, of course, need to fight this. But there is a huge problem—it's logistics. It is challenging to bring something here. Everyone is waiting for a crossing over the Siverskyi Donets River.

As a result of the morning explosions, a high-rise building in the city center was damaged—broken windows, an injured woman, and a cut gas pipe. People complain they cannot call the gas service. In fact, at that moment, most likely, it is simply impossible. So far, only the military has entered the city—the work of utility services hasn't been established yet. At one of the entrances, we can hear an emotional voice: "The russians said they were here forever, but why are they bombing us now?"

"The gas stinks. Can you smell it? It is necessary to tighten the screws somehow. Vitia, how can we call gas utilities?" The questions are complex. Unfortunately, solving them in the first days after city liberation is problematic.

"You can freely go anywhere"

Gossip. Locals approach us for the third time, asking if it's possible to leave the city. The military is already tired of explaining: "Why can't you? You aren't russians, and you are on your land. You can freely go anywhere." Many locals are terrified because of the russian occupation. We see fear in their eyes. In eight months, the russians managed to intimidate people so much that they were afraid of everyone, even a person with a camera. They think that we, journalists, are from Ukraine's Security service and will torture them. We hear it when locals talk to each other.

There is a blown-up bridge at the city exit. The inscription on it is "Slava Trudu" or Glory of labor." In the USSR, where these words come from, they joked that Slava Trudu was a Moldovan football player. No one took this slogan seriously. But for some reason, the occupiers pulled it out and painted it, just like in the torture chamber, where they dragged a flag with a portrait of Lenin.

"It's like a bag of sugar is on me"

We go to the surrounding villages. Fortunately, the war did not affect them much compared to many other villages and towns. There is almost no destruction outside. However, many locals ended up in the torture chamber, where they may have died.

We meet two women. They are still terrified and not ready to tell their stories on camera.

There's a shop on the nearby street. The owner, Tetiana, stands at the door and says it was difficult during the occupation. The shop went to Kupiansk for food because "one has to live somehow."

The woman says she's happy now that everything is fine and that they were terrified of everything, especially their [occupiers'] gaze.

Liudmila, whom we meet a little further on, is a resident of Vovchanski Khutory. She is 63 years old and willingly talks about how life was here during the occupation:

"During the occupation, I felt like I had a bag of sugar on me, and I couldn't take it off. Waking up is good; falling asleep is also good. Life was at the level of death. As the roundup was happening, our street was lucky; there was one russian FSB officer, adequate, who came to our yard and didn't make the soldiers harass us. In other places, people were less lucky—the russians broke their windows and doors, and they were arrested.

When they said we were free, I cleaned the house, washed the floor, and wiped the dust. And I wiped it twice in half a year because I had no will to live. Now, although they are shooting, although it is scary, I am free."

Liudmila continues:

"We were in Vovchansk today, visiting a woman. We are helping her. But we didn't get to her because the shelling started. They [russians] are shooting at residential areas and high-rise buildings. It seems that russia has turned upside down; we live here next to each other—relatives, children, parents, everything is connected. Now, parents and children in russia have to stand in front of the guns because their relatives are being shot at, but no one stands up to authorities.

Once I was in the city and saw a woman walking her dog. Here another woman came out with a small boy, who gave him an umbrella because it was raining. And I thought: now they will start bombing, and what will happen? These people go and live their lives, and maybe they stop living in a second. And so it happened: we had just turned the corner when the russians started shooting. With cluster missiles, I believe, because there were such explosions and so much clapping. A bomb exploded 200 meters from us, we managed to escape, but the people somehow didn't make it. That's how we live."

Liudmila recalls that before the start of the full-scale war, she had a friend in russia:

"I have a best friend from school, and we were friends. We always talked about everything. And after [invasion started], she said that we [russia] would do everything [invade Ukraine] in three days, 'we' as friends are now nobody to each other. We don't talk now. She can't do that. A person must have a core, there must be a homeland, and there must be a platform you live on. And if you lose it, you are nobody. So we became 'nobody' to each other. That's how things are."

"It was scary the most when there was no electricity and no news. There was no electricity from April 7 until the beginning of June. In May, a neighbor bought a generator, and the first thing we did was turn on the news. They were waiting for good news. And no one doubted that it would be so. Let there be no light or food, but we are free. It is my Ukraine and sky, and I am at home."

On the way from Vovchansk, we stop in the village of Prykolotne of the Velykyi Burluk community, where we meet volunteers of the Vokzal Hub. They brought vast aid here—food kits, medicines, hygiene products, sweets, and Ukrainian flags.

Yana Biletska, co-coordinator of the volunteer logistics center for humanitarian aid, says: "We came together with Serhii Ovsiannikov, as well as our friends, partners, and military personnel, to the de-occupied settlement of the Velykyi Burluk community. In general, our center has been operating since the beginning of March. We hand out humanitarian aid. In addition, we are holding a campaign, giving out Ukrainian flags to everyone who wants them, primarily children. Everyone is thrilled to see their native flags. More than 20 communities in the Kharkiv region are under our care. Our priority is de-occupied villages. There was a real humanitarian disaster here."

Ahead are long hours of travel again. Approaching Kupiansk, we see a massive column of smoke. We don't know where on the left bank the strike was. Unfortunately, we don't have time to work in the city of Kupiansk.

35 children taken to russia and "go figure it out"

During the occupation, 35 Ukrainian children were allegedly taken to russia from Vovchansk "for rehabilitation" in August. Unfortunately, we don't learn anything about their fate. When parents try to find where their children are, they are told: "Come to us and pick them up." Of course, it is impossible.