For security reasons, the names of the individuals and some locations may have been changed.

Oleksandr, military, Lviv-Zaporizhzhia-Mariupol

On February 24, I was in the city of Zolochiv, Lviv region, undergoing training as a detachment commander. That's where I first heard about the full-scale invasion. The guys in the barracks started waking up to the news—some at four in the morning, others after receiving calls. Within minutes, 50 of us were on our feet, grabbing our phones and cursing.

I immediately called my wife, who was in Kyiv at the time. Strangely, I learned about the invasion before she did—just from the news. I told her to take her sister and head west since that's where she was from. But she brushed it off, saying, "I have work today."

We quickly got organized. It was clear that Zolochiv, deep in the Lviv region, wouldn't be on the front line. Our entire garrison was in Mariupol, so 35 of us decided to go there—we just needed transportation. The unit refused to issue us weapons, so we left on February 24 without any.

We managed to get two buses: one from the military unit and another from my father-in-law. I called him and asked for his cargo Sprinter, and he gave it to me. That Sprinter later burned down in Mariupol.

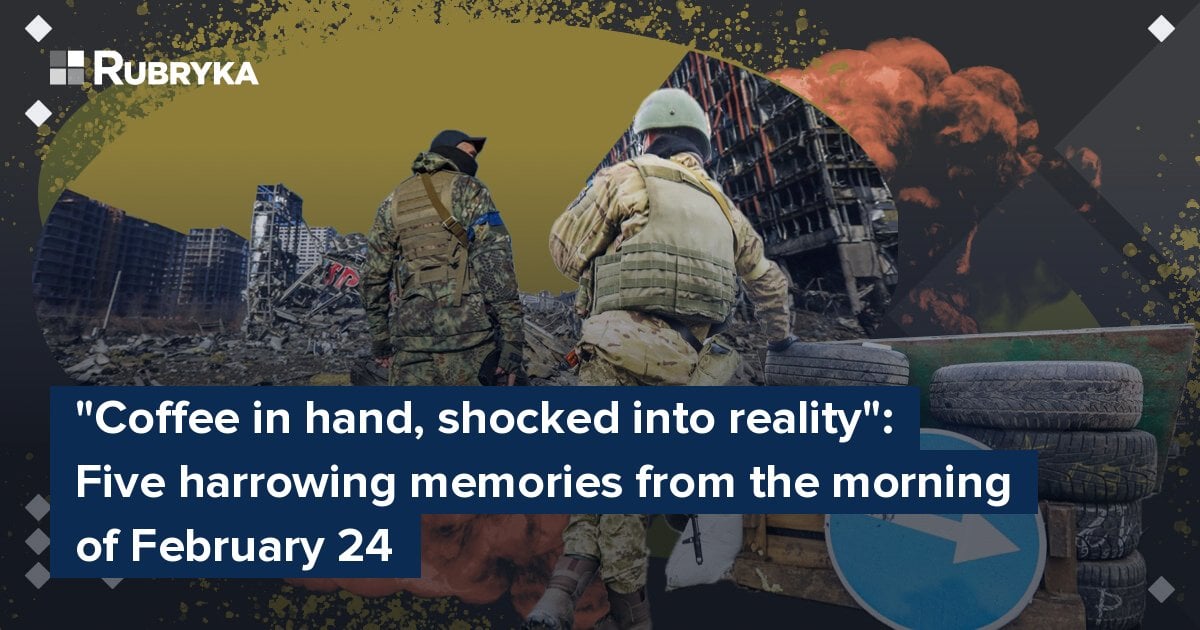

A soldier in the first days of the war. Illustrative photo by Rubryka

We arrived in Zaporizhzhia when Mariupol was already on the verge of being encircled. Everyone knew the Russians were planning to cut it off, so going in without weapons was reckless. Between the two buses, we had only one firearm—a carbine with 300 rounds, brought by a former Azov soldier who had joined us.

In Zaporizhzhia, we reached out to the local Territorial Defense (TRO), told them we were from Azov and heading to Mariupol, and asked for weapons. They simply said, "Okay, come to this address." When we got there, it turned out to be a military unit. They let us in, armed us, and we continued on our way.

By late evening on February 24, we had reached Mariupol. That's when the real defense began—a battle that would last until May 16.

Svitlana, writer, Kharkiv

I live near Pivnichna Saltivka (a district in Kharkiv, Ukraine, that suffered massive destruction during the Russian invasion — ed.). Well, not exactly in, but it begins right behind my house. I woke up at four in the morning to deafening noise.

My first thought was, I'm not going to work today. How absurd. Why did I even think that? I simply couldn't believe that something this horrific could happen—to me, to all of us.

My husband and I immediately ran out to find groceries. There was gunfire in the streets. The shop near the district office had what we needed, but above us, something was flying, exploding…

That's when I understood just how bad things were. People were rushing in every direction. Pets from the day before had suddenly become homeless strays. Families were huddled in basements, seeking shelter from a nightmare that had only just begun.

In a shelter. Illustrative photo by Rubryka

Our house had what the documents called a "model basement"—though in reality, it was just a space with wooden boxes. In one of the rooms, there was even a calendar with a naked woman on it—an odd little bit of humor in the midst of everything.

Going to the basement became essential—it was a place where you could get water and use the toilet. People, mostly strangers from other buildings, started gathering quickly. They arrived with their families, brought bedding, lay down on the wooden boxes, and stayed. Over time, they even set up a small room and began cooking.

Others were also hiding in the house itself. I knew this because, on the first day, I went to check on the apartment where the office was. The premises were fine, though there was no gas—the gas pipeline had been cut off and blocked. But somehow, we still had electricity, and sometimes even water.

That's when a woman suddenly ran up to me, frantic. She shouted that her phone was dead and that she had four children at home. She wanted to take them out of the city, to call a taxi. I was stunned—I had nothing to give her. And in that moment, something inside me shut down. I sank into a kind of cold indifference that would stay with me for years.

I handed her what little I had. "Here's the basement, here's water. Here's a gingerbread cookie—eat it. Take another one for the kids. You can charge your phone down there, ask around for a charger."

And that's when it hit me—I could actually do something.

Yana, combat medic, Kyiv

I was woken up at five in the morning and told what had happened. Then came frantic chats with friends. I spent February 24 making final preparations—I left my cat with a friend, bought essential supplies while the stores were still open, and headed to the Solomianskyi territorial defense collection point.

I had signed up in advance. In January and February, I had gathered documents, visited doctors, and completed medical tests. That morning at 9:00, I was supposed to undergo my final medical examination to sign a reservist contract, which was already at home, signed by me. But instead, by that point, my husband and I had already joined the Armed Forces of Ukraine (AFU).

We had been almost certain this day would come—it was only a matter of time. I had hoped to complete my hospital training in March, but the war started earlier, and I never got the chance.

From the military registration and enlistment office, we were sent to the district state administration, where territorial defense units were being organized. The process was surprisingly structured. A battalion was formed there and later divided. The line of volunteers wanting to join the TRO was massive. Some of the officers already recognized me, and I ran into a few familiar faces.

For the first four days, I helped clerks register new arrivals. My home printer turned out to be useful when the office equipment broke, and later, local business owners donated a few more.

We processed volunteers, had them interviewed by commanders, and helped form new units. In the end, I was placed in one of the last combat units—right at the final stage of the battalion's formation.

A checkpoint in the first days of the full-scale invasion. Illustrative photo by Rubryka

Oleh, consultant, Mariupol

My family and I moved to Mariupol and decided to stay. [Oleh is an resettler from Donetsk—ed.]

After living in Mariupol for eight years, we had finally settled in. We even received an apartment from the state—a nice place in a good neighborhood. I had a stable job, my wife did too. We lived our lives, made plans, hoped for the future, relied on certain things.

Our son was born in Donetsk but grew up in Mariupol. He went to kindergarten there, then school, made friends. But all of that ended on February 24.

I remember that day down to the minute. I woke up as usual, got ready for work, made coffee, turned on the TV—and froze. Every channel was showing… well, I don't even know how else to describe that moth talking about some kind of "special operation" and "denazification."

After the shelling. Illustrative photo by Rubryka

I had heard some rumors before, but I didn't fully grasp what was happening. Like most ordinary people, I didn't yet understand the scale of what was unfolding. So, I just went to work as usual.

I worked as a consultant in a hardware store. When I arrived, everyone was confused—no one knew anything for sure. People started talking among themselves, trying to piece together what was going on. Then, the store director announced that there would be no work today. He added that if possible, at least one person from each department should come in the next day to keep the store running.

When I left, I immediately noticed the long lines at ATMs—people were rushing to withdraw cash. The stores were also packed with customers buying up flour, pasta, canned stew—anything they could stockpile.

When I got home, everything still seemed normal. The sun was up, life went on, and nothing felt particularly different.

But by February 25, when I arrived at work, explosions could already be heard in the neighborhood. People were now buying candles, portable stoves, gas burners, and gas cylinders. I bought a small one-burner stove, and it ended up being a lifesaver. My only regret was not buying more gas cylinders while I had the chance.

Diana, doctor, Dnipro

We weren't prepared for a full-scale invasion. My husband is also a doctor, and on the night of February 23-24, we were at the hospital. It was the usual hectic night shift—many patients, including children, all suffering from fevers, stomach issues—everything felt normal. We typically saw about 120-140 patients a day, so by the end of our shift, it was like being a squeezed lemon, completely exhausted, trying to sneak in a cup of coffee whenever possible.

It was just another night on duty. We worked until around 4 in the morning without any breaks, hardly stepping outside the department. Then, at some point, I found myself in my resident's office. I sat down to drink coffee and unexpectedly dozed off, even though we're not supposed to sleep at work.

I woke up to strange sounds. One of our medical directors called to check if everything was okay at the hospital. I stepped outside and was immediately hit by the noise and explosions. At that moment, our entire lives changed.

An influx of people into one of the hospitals. Illustrative photo by Rubryka

I wouldn't say it was scary. As a doctor, my immediate focus was on practical matters: preparing the emergency room, checking the tourniquets, ensuring we had all the necessary medications—everything we needed to provide assistance. Then my husband called me and said, "Diana, I won't be going to work anymore." He headed straight to the enlistment office. That's how my first day of the war began.