What's the problem?

Black granite engraved with the names of the deceased, a base covered in fresh or artificial flowers — this is a typical memorial for the fallen soldiers in Lviv, Kharkiv, Dnipro, Kyiv, and nearly every town and village across Ukraine. These monuments hold deep meaning for those who erected them — the grieving families determined to immortalize their sorrow and the memory of their loved ones.

These memorials often remain confined to personal grief. They rarely convey the stories of the fallen to strangers, nor do they spread the memory about them. The tradition of creating such memorials dates back to Soviet times when impersonal lists of names carved in granite were a common way to commemorate heroism and sacrifice.

Public spaces dedicated to remembrance, however, should not only preserve but also propagate memory. According to historian and public history expert Anton Liahusha, memorials need to be inclusive, personalized, and interactive to achieve this goal:

"A monument dedicated to tragedy should be understandable to everyone — a child, an older person, the educated, and the uneducated alike. If we want the memory to live and remain relevant, we should not erect Soviet-era-like 'alleys of glory,' which people rarely visited because they didn't know what to do there."

Historian Anton Liahusha. Photo: Facebook

With today's technology, Ukraine can use digital tools to improve remembrance practices: QR codes, audio, and multimedia exhibitions can bring history to life.

"The genocidal war Russia is waging against Ukraine is not only a fight for survival but also for freedom. The new culture of remembrance is a story of freedom, which defines itself by rejecting the Soviet past," says Anton Liahusha.

"On the other hand, we still see people fighting Soviet influence using Soviet methods. This creates a divide among the relatives of the fallen — some want traditional, grand Soviet-style monuments, while others insist on moving away from that approach."

People gravitate toward what is familiar, comprehensible, and quick to execute when searching for solutions. While local authorities take years to establish something as important as the National Military Memorial Cemetery, grieving families want to honor their loved ones now.

"We observe a gap between what people on the ground expect — those burying their loved ones daily — and the slow response from authorities. People need tangible acts of commemoration, especially when it comes to burying the fallen soldiers. Families seek a national-level acknowledgment of their loss and sacrifice. They cannot and do not want to wait — grief does not wait," the expert explains.

What's the solution?

To fundamentally improve the situation, the Ukrainian government must take the initiative with a clear political will and commit to preserving Ukraine's memory and identity. The future of Ukrainian remembrance culture — and how this war will be remembered — depends on leadership.

"Collective memory is directly linked to collective identity. Shared narratives about the past — whether of defeats or victories, tragedies, myths, or historical facts — shape our understanding of who we are. Our collective story about our shared past, be it heroic or tragic, determines our common values, traditions, and symbols," says Liahusha.

Collective memory can be shaped by governments, media, cinema, music, television, social media, commemorative days, museums, and rituals. These elements become part of a nation's identity because how people remember their past defines them.

Commemoration practices vary across countries, but some rituals are universal, such as lighting candles or observing moments of silence. Let's look at how different nations honor their fallen.

How does it work?

The Wall of Pain

In 1991, Croatia declared independence from Yugoslavia. Serbian forces, seeking to maintain control, opposed the move, which led to a series of wars that claimed tens of thousands of Croatian lives. Croatia fully regained its territorial integrity only in 1998.

The memory of those years left a deep mark on Croatian society, where honoring the fallen became a part of the national remembrance culture. Each city has commemorative dates marked by candlelight vigils, museum visits, moments of silence, and mourning rallies.

In 1993, Croatian refugees in Zagreb built the Wall of Pain to honor the victims of Vukovar, a city that remained under Serbian occupation at the time. The monument consists of 13,600 bricks, each bearing the name of a missing or deceased person. When Vukovar was liberated, the tradition expanded: Croatians formed a human chain each year in remembrance.

Wall of Pain, Zagreb, 1993. Photo: croatianhistory.net

The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier

The first Tomb of the Unknown Soldier was established after World War I, setting a precedent for recognizing war as a tragedy rather than merely a demonstration of heroism. Unlike grand, impersonal monuments of the past, this memorial honored individuals and their contributions — soldiers, medics, cooks, and others.

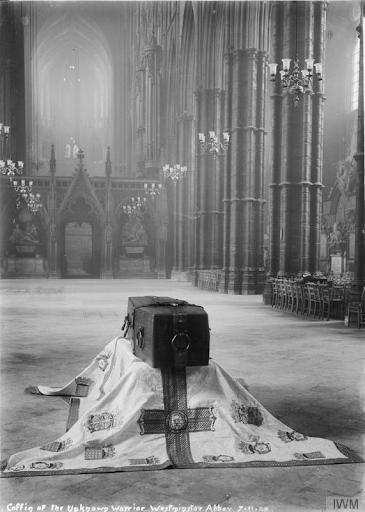

Burial ceremony, 1920. Photo: Imperial War Museums

The Westminster Abbey in London held the burial ceremony of an unknown soldier. It was a historic moment, as the site had previously been reserved for royalty. The king walked behind the coffin during the procession, followed by senior officers and nobility.

Such memorials humanized war, drawing attention to the sheer number of lives lost. They also pushed people to reassess the role of military leadership and highlighted the sacrifices of ordinary people.

The culture of honoring the Unknown Soldier contributed to a new approach to military burials, ensuring that all service members, regardless of rank or position, are laid to rest with identical headstones.

This practice was later adopted to expand Arlington National Cemetery in the United States. Established during the Civil War, Arlington now serves as the final resting place for war veterans, prominent political figures, judges, and astronauts. Every grave has the same headstone, with only the inscriptions differentiating them.

Arlington Cemetery. Photo: arlingtoncemetery.mil

In contrast, the Soviet Union manipulated the concept of the Unknown Soldier for propaganda. Rather than honoring the fallen, memorials often served ideological objectives. Instead of acknowledging national grief, it focused on glorifying "national heroism" through mass demonstrations, alleys of glory, and towering monuments to Soviet soldiers. Tombs were dedicated to the "Soviet soldier," an anonymous figure with no family or roots, devoted solely to the dictator and ideology.

Light the candle

Lighting a candle to honor the dead is widespread across cultures and religions. In Ukraine, this practice is deeply tied to the annual Holodomor Remembrance Day, which commemorates the victims of the Soviet man-made famine and the genocide of the Ukrainian people. In 2003, genocide researcher James Mace suggested a nationwide ritual: placing a lit candle on the windowsill at 4:00 PM.

According to historian Anton Lyagusha, this practice has become an important marker of Ukrainian identity:

"When you ask someone, 'Why aren't you lighting a candle on your windowsill?' and they reply, 'Why should I? What are you talking about?' — you realize that this person may not share your identity or even your nationality. This is about political nationhood. Collective memory acts as a powerful identifier, helping distinguish between 'us' and 'them' and shaping national spaces."

Such rituals build collective memory and community interaction.

Every year, the National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide invites visitors to light remembrance candles on the hill near the museum. This is followed by a collective screening of a documentary about the Holodomor.

Remembering personal stories

In China, a wall dedicated to martyrs — people who fell in conflicts — features QR codes that visitors can scan to learn about each individual's life and story.

Longhua Martyrs' Memorial Park. Photo: eng.mod.gov.cn

Similarly, in Ukraine, the National Museum of History hosts an exhibition about the defenders of Azovstal. The exhibition portrays the fallen soldiers through their personal narratives — who they were before the invasion, what they loved, and where they studied.

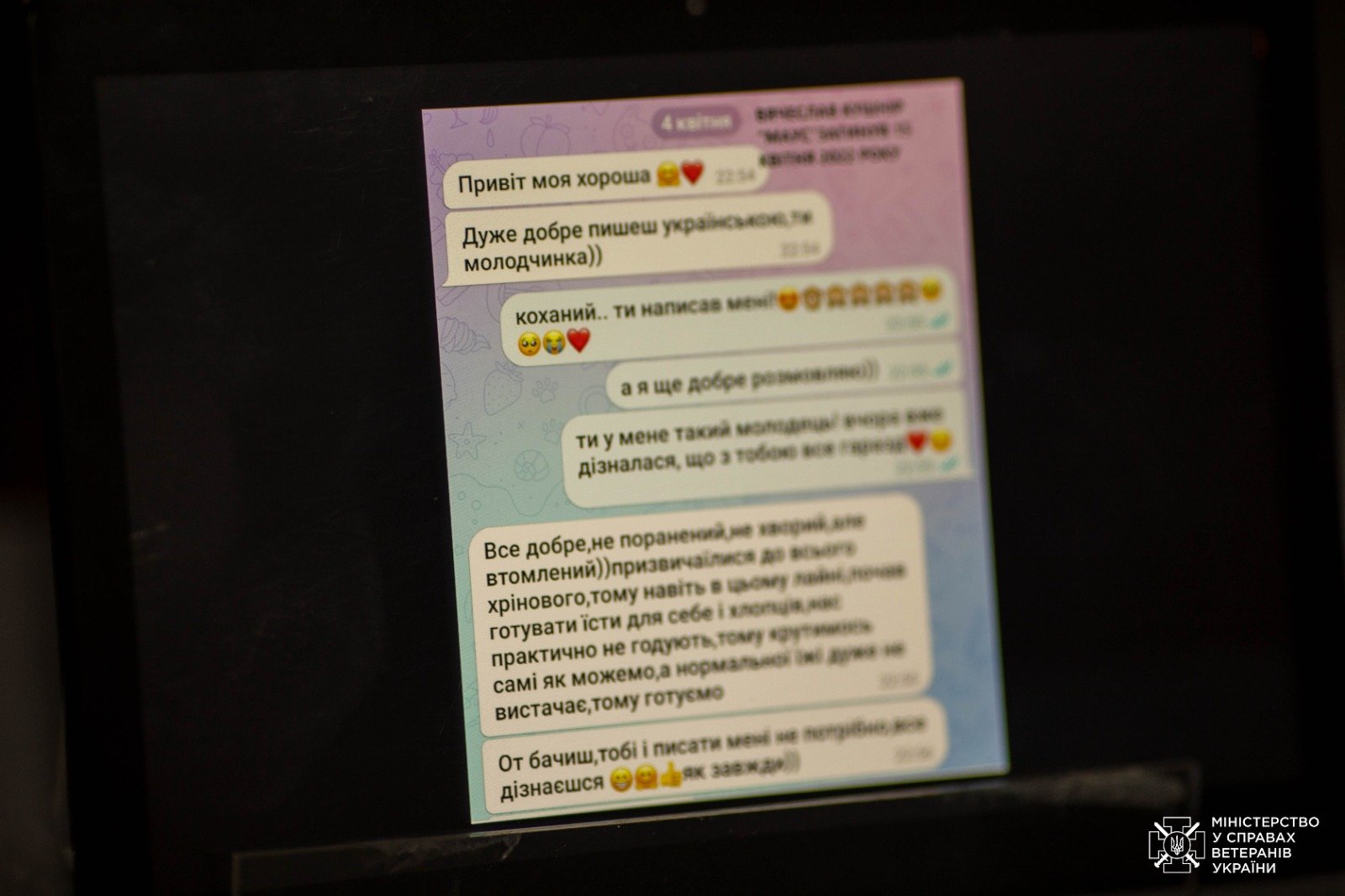

Museum exhibits: combat boots, a phone, and a screenshot of a personal conversation. Photo: Ministry of Veterans Affairs of Ukraine

The exhibit showcases personal items of soldiers: cherished childhood toys, handwritten letters, combat boots, and more. It serves as a reminder that each fallen soldier was, above all, someone's son, brother, or friend. Each fallen soldier was, first and foremost, a human with a unique and meaningful story.

We created this article as part of the Recovery Window Network. For more information on the recovery of war-affected regions in Ukraine, visit recovery.win