Ukrainian art has often found itself unrecognized due to Russian imperial ambitions. Throughout the history Ukraine and Russia have shared, the northern neighbor has repeatedly appropriated, if not killed or oppressed, Ukrainian artists and claimed their artworks as its own. Rubryka lists five artists who — perhaps to your surprise — are, in fact, Ukrainian.

Kazimir Malevich

Probably the most famous Ukrainian artist on this list, Kazimir Malevich, the son of a Polish father and a Ukrainian mother, was born in Kyiv and raised in various towns across Ukraine. Despite being a citizen of the Russian Empire and then its Soviet successor, Malevich identified himself as Ukrainian, which echoed in his artistry throughout his life.

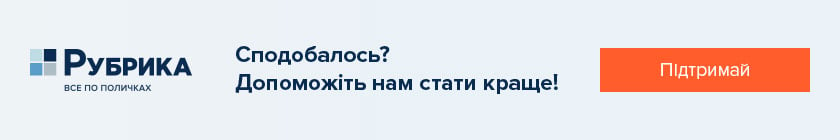

Black Square, 1915

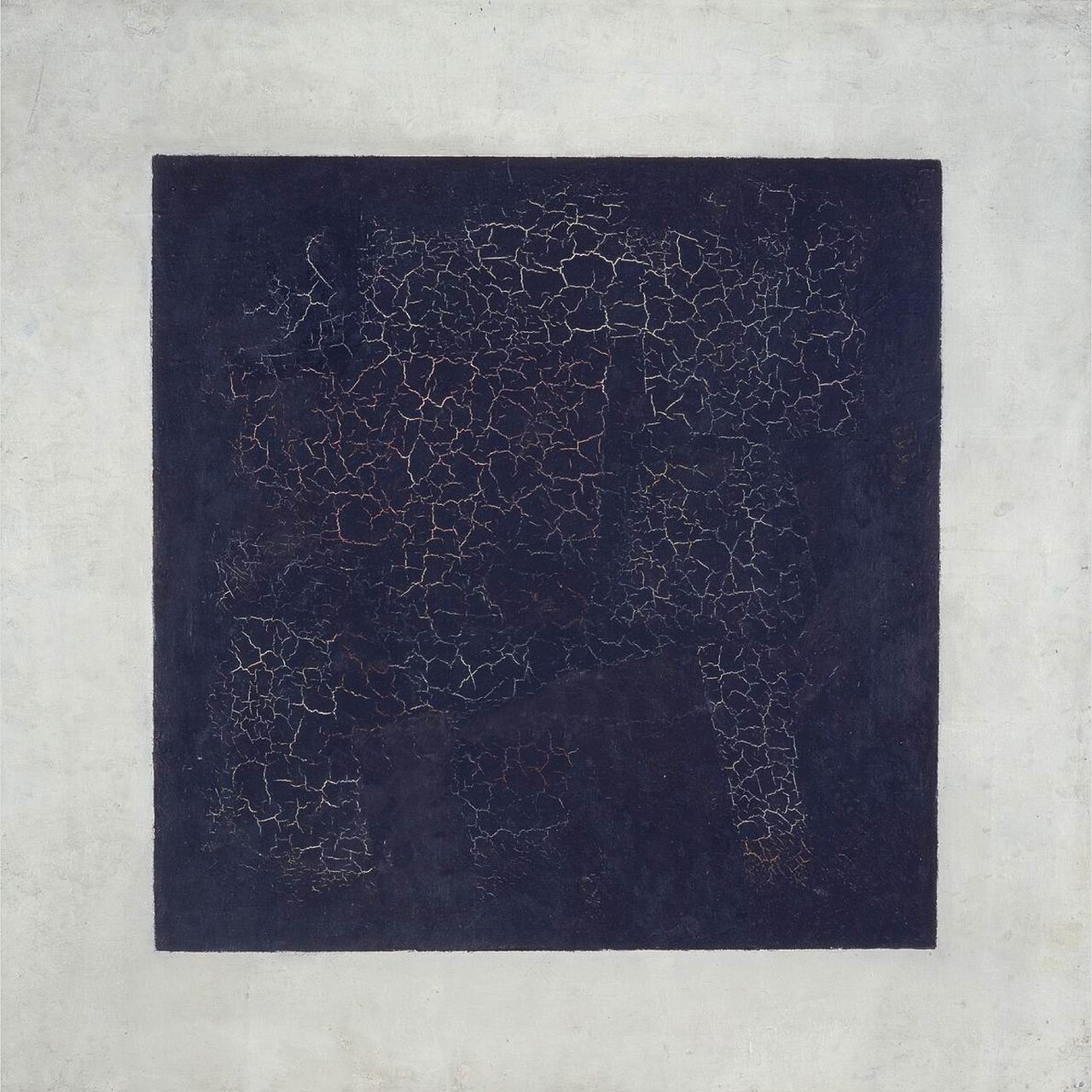

Malevich's most renowned work, Black Square, was the epitome of his abstract art style, called Suprematism. It was based on simple geometric shapes and colors. Esteemed art historian and avant-garde researcher Dmytro Horbachov said Malevich took inspiration from Ukrainian traditional folk art and argued that geometric ornaments of Ukrainian houses and decorated eggs, Pysankas, laid the foundation for simple forms of Suprematism.

Pysanka motifs in Malevych's works, 1920-1922

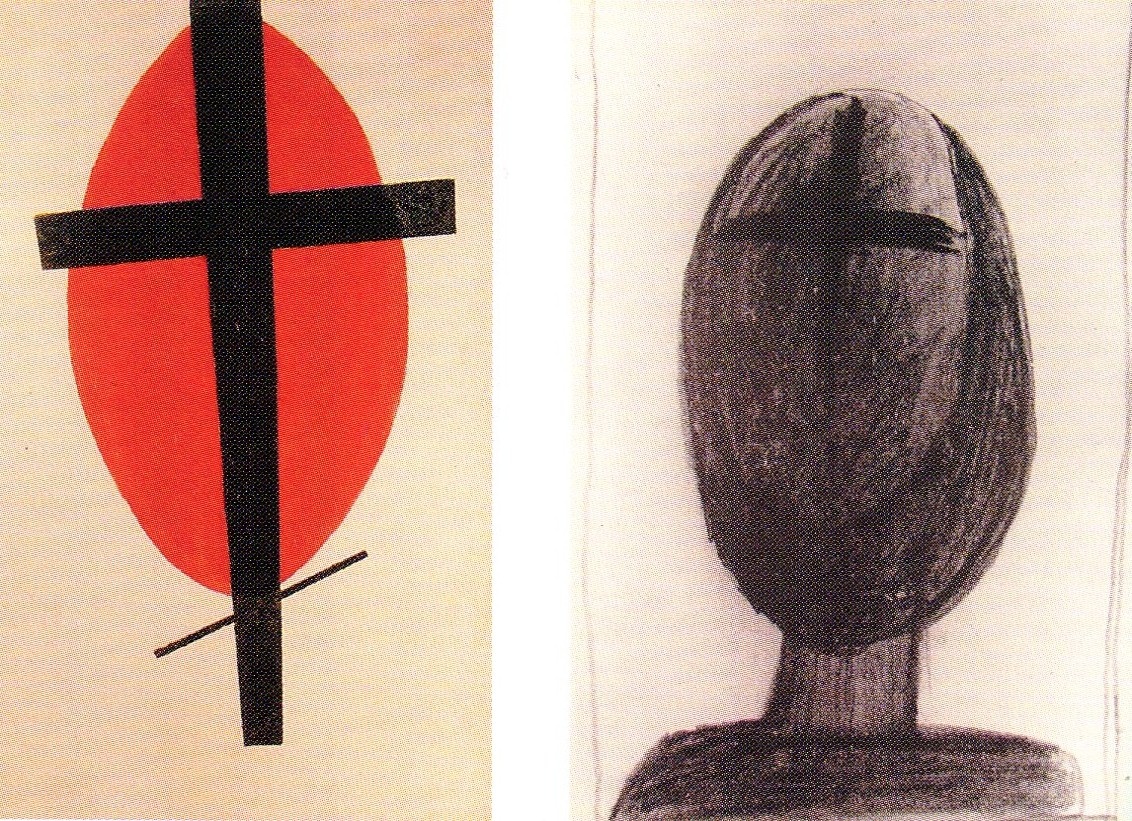

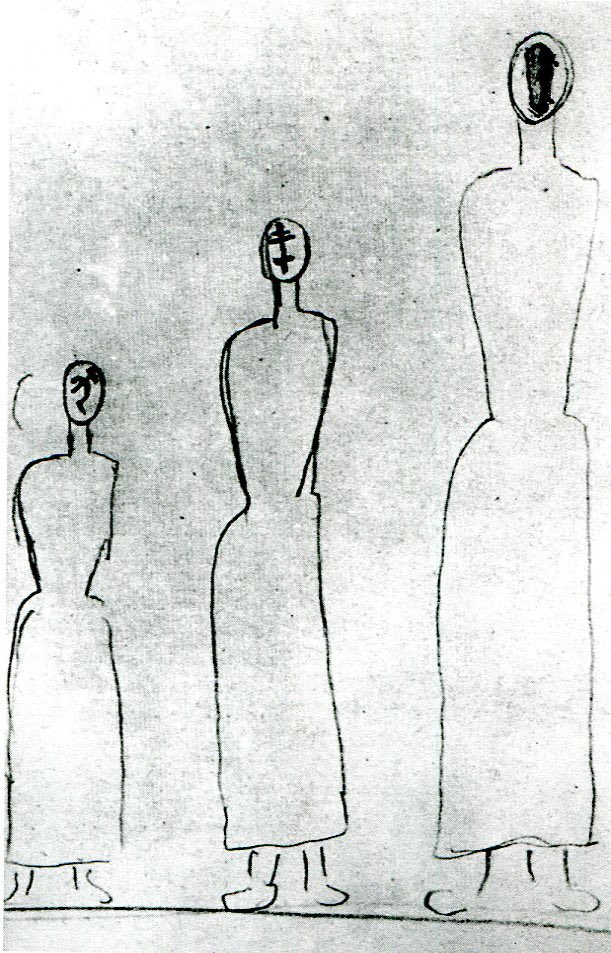

In his later years, Malevich created paintings portraying the life of Ukrainian farmers. He was also one of the few who risked depicting the Holodomor, a 1930s man-made famine organized by Soviet authorities. His piece "Where There is a Hammer and Sickle, There is Death and Hunger" shows three figures whose faces Malevich replaced with the Soviet Union and death symbols. Many of his paintings contain subtle messages to protest Soviet crimes against Ukraine, for which he was repressed, accused of espionage, and threatened with execution.

"Where There is a Hammer and Sickle, There is Death and Hunger," 1932-33

Sonia Delaunay

Sonia Delaunay, the first living woman artist in history to have a solo exhibition at the Louvre, was born into a poor Jewish family in Ukraine's southern city of Odesa. She was orphaned early in life and then adopted by her uncle.

Sonia Delaunay, Musée National d'Art Moderne Paris, 1967

Her art is not displayed in Ukrainian museums, as she spent most of her life in France and Spain. Despite living abroad, she was still influenced by Ukrainian culture and attributed the use of vibrant colors in her art to her origin. In her memoir, she wrote, "I love bright colors. These are the colors of my childhood, the colors of Ukraine."

Rhythm Colour No 1076, 1939

While living in Paris, Sonia and her husband, Robert, developed their unique art style. The couple prioritized color over form and used the color theory to create the play of contrasting colors in concentric circles. They called the style ophism after Guillaume Apollinaire, a celebrated French poet and family friend, suggested the name.

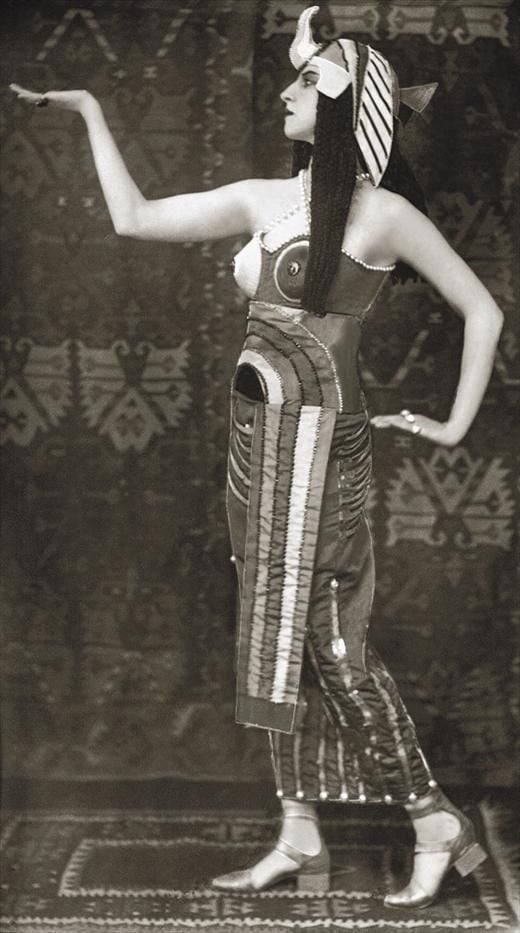

Ballerina Lubov Tchernicheva portrays Cleopatra in the Balanchine ballet Caesar and Cleopatra in Sonia Delaunay's design, 1920

Sonia Delaunay in her studio at Boulevard Malesherbes, Paris, France, 1925

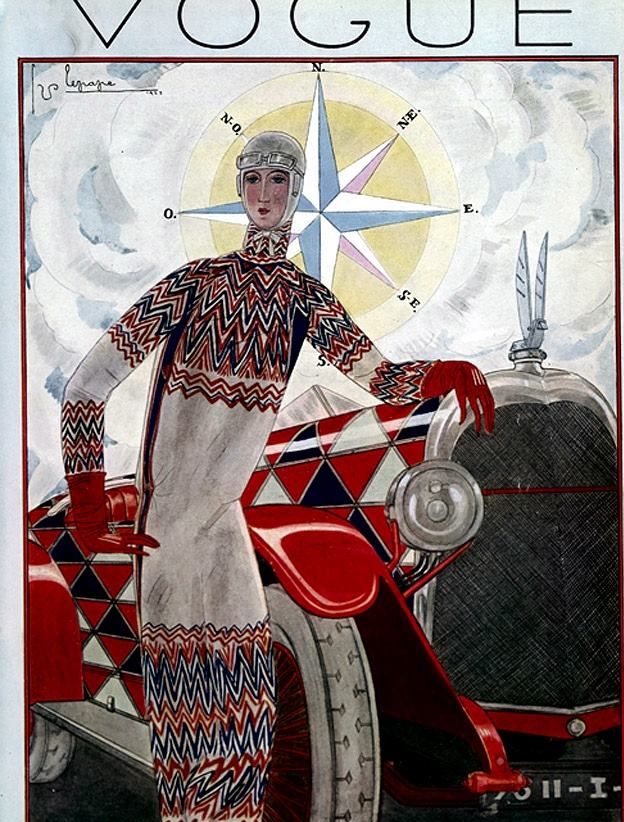

At 33, Sonia entered the fashion world, designing wearable art — garments called "poem-dresses" — and film costumes at her studio in Madrid, Casa Sonia. Later, she created geometric patterns for fabrics and home decor. Her biggest success in France, where people always acknowledged her Ukrainian roots, came in 1925 after she held a personal exhibition featuring her designs for decorative objects, clothing, and even cars.

One of her garments, an optical dress, was used for the 1925 American Vogue cover illustration.

Ivan Aivazovsky

Russian propaganda has always brazenly tried to appropriate the famous Ukrainian artist Ivan Ivaizovsky. While the painter was born in imperial times in the city of Feodosia in Crimea — part of Ukraine now under illegal Russian occupation — he never called himself a "Russian artist" in his lifetime. Aivazovsky was, in fact, of Armenian origin and was fluent in the Ukrainian language because his parents, descendants of migrants from Western Armenia, were from the area near Ukraine's western city of Lviv.

A Moonlit Night on the Crimean Coast, 1875

The Shipwreck at the Tempest, 1889

Internationally known for his marine art, which depicts the turbulent waters of the Black Sea, Aivazovsky also painted Ukrainian landscapes, including steppes and the Dnipro River, scenes from the lives of Ukrainian traveling merchants, called "chumaky," and farmers and their traditions. These include "Reeds on the Dnipro River near the town of Oleshky" (1857), "Ukrainian landscape at night" (1870), "Wedding in Ukraine" (1892), and many more.

Reeds on the Dnipro River near the town of Oleshky, 1857

Ukrainian Landscape at Night, 1870

Wedding in Ukraine, 1892

Chumaky Relaxing, 1885

Aivazovsky worked abroad in Italy, France, England, the Netherlands, and Turkey and could settle in any country, but the artist always returned to his hometown, Feodosia. He spent most of his life supporting the city with donations to develop local infrastructure, education, and art.

Oleksandra Exter

Ukrainian avant-garde artist Oleksandra Exter had a fruitful career in many art directions, from painting and graphic art to clothing and stage design in theatre and cinema. When she was a young girl, her family moved to Kyiv, where she was raised and then formed as an artist, studying at Kyiv Art College under distinguished Ukrainian painter Mykola Pymonenko.

Still Life with Eggs, 1914

The researcher of her work, Heorhii Kovalenko, said in his monograph that Exter carefully studied Ukrainian folk art and admired its color, rhythm, and composition. She went on "real scientific expeditions in search of ancient peasant embroidery, liturgical sewing, and weaving items." Inspired by research, Oleksandra used saturated paints to create art pieces, like Three Female Figures (1909-1910), now displayed in Ukraine's National Art Museum.

Three Female Figures, 1909-1910

During her studies in Paris, Oleksandra came across new anti-establishment art styles and experimented with her work. When Exter returned to Kyiv, she created an art studio, which played a vital role in the Ukrainian avant-garde movement and shaped European perceptions of Ukrainian art. She supported other contemporary artists in her workshop and developed the first 3D theater stage decorations for city theaters.

After immigrating to Paris, Oleksandra tried to preserve her connection to Ukraine. She decorated her small residence in a Parisian suburb, Fontenay-aux-Roses, with Ukrainian ceramics and embroidered towels and treated her guests to traditional dishes, like varenyky.

Venezia – Panello Decorativo, 1924

Oleksandr Arkhipenko

Exter's friend and college classmate, Oleksandr Arkhipenko, is now considered one of the most renowned sculptors of the 20th century and one of the founders of Cubism. He opposed traditional notions of what art should be, learned art independently, and believed art schools were too conservative.

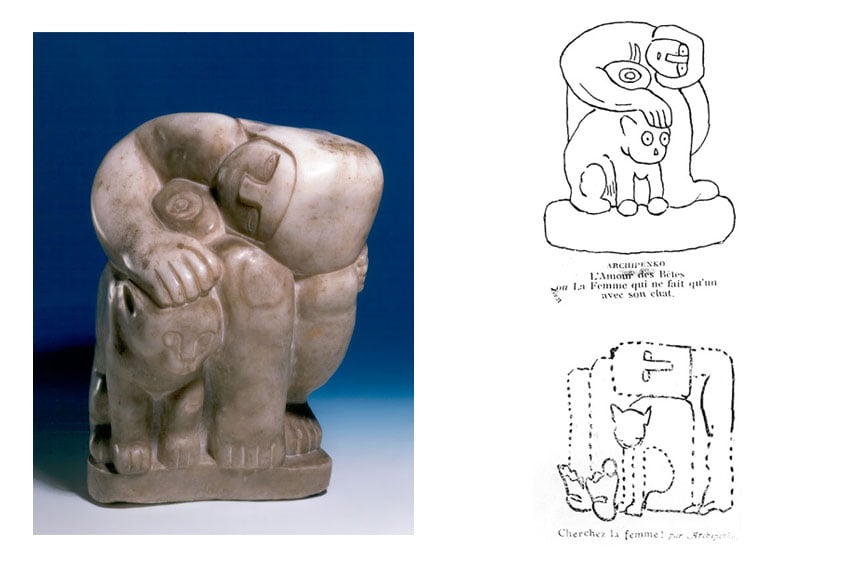

A Woman with a Cat, 1911, and its caricature in a French newspaper

The Ukrainian artist's work became infamous, provoking ironic remarks from the audiences and critics. His sculpture "A Woman with a Cat" was mocked in a French newspaper in a caricature titled "Cherchez la femme" or "Find the Woman."

Woman Combing her Hair, 1915

The Kyiv-born sculptor identified himself as a Ukrainian artist and repeatedly explained in interviews why his art belonged to Ukrainian culture. He said he was inspired by "the vast Ukrainian steppe" and ancient Scythian stone idol figures when creating his small figurines.

Carrousel Pierrot, 1913

Arkhipenko's piece, Carrousel Pierrot, is listed among the fundamental works of 20th-century sculpture. It is reminiscent of rural wooden polychrome sculptures, many of which have been preserved in Ukrainian churches since the late 17th century.

When Arkhipenko immigrated to the US, he kept in touch with his Ukrainian peers and the Ukrainian art scene and was involved in the diaspora. He was an honorary member of the Association of Ukrainian Artists of America and designed the Ukrainian pavilion at the 1933 Century of Progress exhibition in Chicago.

King Solomon, 1963