What is Ivan Kupala?

The boisterous festival of young people, Ivan Kupala, or Ivana Kupala/Kupaila, takes place on the eve of June 24 (Gregorian calendar) or July 7 (Julian calendar). In the past, it was the last climactic celebration that finished the summer holiday cycle. Scholars have conflicting views on who Kupalo is. Old written sources describe Kupalo as a pagan god of fertility, to whom people offered bread, the primary fruit of the earth, as a sacrifice. Some researchers link Kupalo with the god of the sun. In any case, Kupalo, as a deity, is associated with fire, water, and earth, which explains why all the midsummer rites involve these three elements.

Ukrainian Midsummer celebrations: a Ukrainian woman in front of a bonfire on the Ivan Kupala in Pyrohiv, Kyiv, Ukraine, on July 6, 2017. Photo: Sergei Supinsky/AFP

After the adoption of Christianity, this holiday was merged with the celebration of the birth of John the Baptist, gaining the name Ivan (the Slavic version of John). Though the church didn't approve of pagan traditions, even calling them "satanic" or "devil-like," it didn't ban them. Instead, it tried to fill customs with Christian senses because it couldn't eradicate the people's strong desire to honor nature. For Ukrainians, the holiday was a vital time to say farewell to summer and enchant themselves with happiness and prosperity, which included a rich harvest and a successful marriage.

Magic of Ivan Kupala

Ukrainian Midsummer celebrations: Ivan Kupala Eve by Ukrainian artist Ivan Sokolov, 1856

"This festival took place when the sun reached its peak — rising highest in the sky, giving the most heat and light, showing its greatest magical power for the plant and animal world and humans," says ethnographer Stepan Kylymnyk. Ukrainians believed the holiday had a supernational effect on nature. Everything in forests and fields bloomed and multiplied, and water and fire could purify and protect people from all evil and misfortune.

An illustration of the story "Ivana Kupala Eve" by Ukrainian writer Mykola Gogol. Photo: Wikimedia

According to ancient legends, the divide between the worlds of humans and the afterlife was coming down during the Kupala night. Nature awakened, and all the secret forces of forests, fields, water, and mountains were free to roam and make noise and commotion. Plants and trees rejoiced in the fun, moving around the forest and talking to each other. All the dark forces — witches, sorcerers, werewolves, vampires — came together for meetings on hills to build plans against the good spirits. Ukrainians believed that evil and good fought all night until the third crow of the rooster.

Ivana Kupala was believed to be both terrifying because of the wandering dark spirits and hopeful because, due to the powerful energy the night possessed, one had a chance to find happiness, a lucky fate, and wealth. To protect themselves from evil and gain desired love and prosperity, Ukrainians performed special midsummer rituals and held celebrations that involved fun games, dances, and songs. The rites were set up near nature — on meadows near the forest and water, like springs, wells, or rivers.

Ukrainian Midsummer celebrations and rituals

Magical herbs and a flower of happiness

A young woman in a wreath and a long white national shirt collects wildflowers. Photo: julitt/Depositphotos

The old Kupala myth says that herbs and flowers from the forest, fields, and gardens gain magical healing properties bestowed upon them by good spirits and the sun. Medicinal herbs sown by mermaids, nymphs, and other "forest creatures" reveal their true healing power only when gathered at midnight or early in the morning on Ivana Kupala. Ukrainians still have a tradition of picking potent plants, but no longer use them to treat illnesses like their ancestors did. Religious people preserved the customs of blessing herbs in a church and keeping them in the most sacred corner of the house.

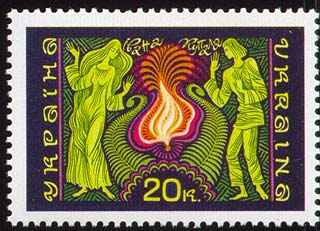

A Ukrainian stamp dedicated to Ivana Kupala's fern flower, 1997. Photo: Post of Ukraine

Another folk tale tells of the ritual of seeking the flower of happiness, which some Ukrainians still jokingly engage in. In the past, during the night, crawling with evil spirits, brave young people were looking for the red fern flower that looked like a flame. According to the myth, whoever found and picked it would get knowledge of the world and gain the ability to find any hidden treasure. This lucky person would charm the most beautiful partner, have the wealthiest harvest, protect their field from hail and heavy rain, and not fear evil forces. Ukrainians believed the flower to be challenging to come by because the fern bloomed only briefly once during the night of Ivana Kupala and was guarded from people by evil forces.

Kupalo and Marena

Ukrainian Midsummer celebrations: Marena and Kupalo at the National Museum of Folk Architecture and Life of Ukraine in Pyrohiv, Kyiv, Ukraine. Photo: ZN.UA

Another mysterious ritual of the Ukrainian Midsummer that has been preserved for centuries is the making of "Kupalo" and "Marena." The village youth go to the meadow near the river to build the human-sized "dolls," with which they perform a series of symbolic acts and games. The young women and men joke and sing back and forth while making the figures.

Marena at Spivoche Pole Festival at the National Museum of Folk Architecture and Life of Ukraine in Pyrohiv, Kyiv, Ukraine. Photo: Authentic Ukraine

The boys make a male-like "Kupalo" out of a willow branch and straw, giving it a mustache and a beard and dressing it in a man's pants, a shirt, and a hat. At some distance from the boys, the girls make "Marena," a woman-like figure out of a cherry branch. They adorn it with wreaths made of flowers and plants and dress it in an embroidered shirt, a necklace, a headscarf, and a skirt. After the girls finish "Marena," they sing songs and perform a circle dance around a doll, honoring the life-giving sun.

People celebrate Ivan Kupala in the National Architecture and Household Museum in Pyrohiv, Kyiv, Ukraine, July 7, 2013. Photo: Oleksii Chumachenko/Depositphotos

Afterward, boys tear apart both male and female dolls, scattering the pieces around, burning them, or drowning them. Researchers have yet to determine for sure what the ritual means. Some say the dolls symbolize the female and male energies of the god of fertility and are burned or drowned to represent the death of summer and the rebirth of nature. Others say dolls are supposed to be a sacrifice to nature.

Wreath weaving and divination

Wreath divination. Photo: Authentic Ukraine

During the Ivana Kupala celebration, Ukrainian women and girls traditionally gather plants from fields, woods, and gardens and weave wreaths. Each wreath must include all the magical herbs and flowers, such as lovage, burdock, periwinkle, rowan, motherwort, cornflowers, poppies, ears of wheat, marigolds, and others. After gathering enough plants, girls sit in a circle near the river or on a forest clearing close to the Kupala fires, singing and weaving two Kupala headpieces. After the girls finish the wreaths, they move with them in a circle dance, holding one headpiece in each hand up to the sky.

Afterward, it is time to set wreaths afloat on a river and start divination, like their foremothers. In the past, each girl guessed her fate and made a wish for her future. Then, she observed with bated breath if a wreath caught up or came together with another, fell apart, or went to the river bank. The girls whose wreaths were the fastest would have a happy marriage. This ritual was a prayer to gods of love and fertility, and wreaths symbolized fate, love, success, and prosperity. If the divination brought bad fate, girls could avert it by the highest powers of fire and water.

Ivan Kupala bonfires and healing water

A man jumps over a fire during the Ivana Kupala celebration in Kyiv, Ukraine, on July 6, 2018. Photo: Valentyn Ohrenko/Reuters

Fire is an indispensable part of the Kupala celebrations, which Ukrainians believed could cleanse the body and soul from illness and misfortune. On the holiday's eve, only boys gather on a forest glade or near a river and set up smaller fires. Then, according to tradition, every young man or woman must take turns jumping over the Kupala fire to be purified and protected from evil.

Whoever landed best would have a good harvest and be healthy. If someone fell during the jump, something unfortunate would happen to them in the coming year. After single people finish the ritual, young couples start jumping over the flame. If they jump successfully without touching the fire or stumbling, they marry and live happily ever after.

Circle Dance on the Ivan Kupala. Photo: Authentic Ukraine

Each Ivana Kupala celebration also needs one large bonfire, which young men build of a long or rather tall piece of wood or a fallen tree with twigs around it. Four boys light it simultaneously from four opposite sides. Once the fire illuminates the celebration site, girls and boys play drums, sing, and circle the bonfire. Remnants of the Kupala bonfire were believed to be magical. If a witch, vampire, or werewolf were to get something from this fire, they could cause harm.

A Ukrainian girl bathes in a river. Photo: UNIAN

Ukrainians also believed that only on Ivana Kupala Day, water, like purifying fire, gained magical properties. They traditionally bathed in rivers and lakes only in the morning after celebrations; bathing at night was forbidden because water was considered dangerous. Water in wells was also magical: each girl hurried to be the first to draw water, take a sip, and wash her face. The morning dew was also considered healing, so women rolled in the wet grass and washed their faces with it for beauty. These water traditions have been preserved to this day.